John and Mary Kormendy: Antarctica 2026

This web site contains the pictures from our 2026 January/February trip to New Zealand and our Aurora cruise, the "Ross Sea Odyssey" to Antarctica. This will be our 3rd cruise to Antarctica; the first 2 were via Aurora and Seabourn, respectively -- see links here.

This trip is now under way and pictures are being added when I have time. If you see a long delay since I last added pictures, the reason could be that I have no internet connection in Antarctica or that my logins into the University of Texas computers that host my web site have temporarily failed.

The purpose of this web site is to catalog our memories, not to showcase the trip for public readers. So I include pictures that are not very good when they document sightings that are important to us.

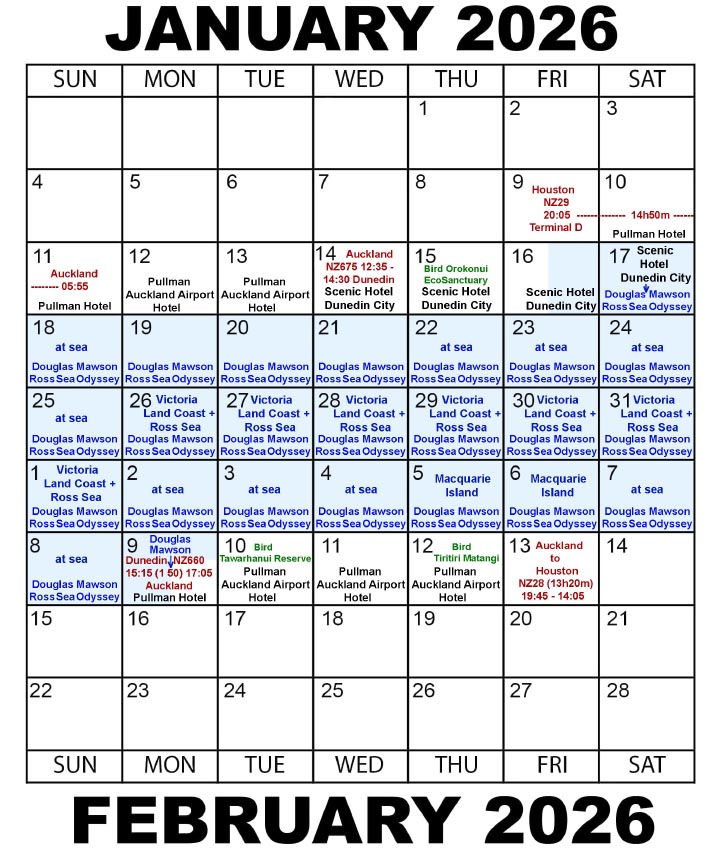

Calendar

Trip Birds

Travelog and Bird Pictures

January 15 and 16, 2026: Orokonui Ecosanctuary, near Dunedin, New Zealand

South Island Takahe -- closely related to Australasian swamphen and the world's biggest rail. Originally discovered in 1847-1848 based on fossilized bones, it was thought to be extinct, like the much larger Moa. A tiny population of about 100 birds was discovered in Fjordland on the South Island, but early encounters -- always of just one or two birds -- were exploitative. The minimum world population is estimated to have been roughly 100 birds. Since then, aggressive protection and relocation to predator-free islands and sanctuaries has increased the population to ~ 600 birds now, increasing (according to Wikipedia) by about 8 % per year. We first saw Takahe at the protected island of Tiritiri Matangi during our 2011 birding tour to New Zealand. Now they thrive in many sanctuaries, including Orokonui. New Zealand's focus on saving endangered bird species is impressively dedicated and successful.

Kaka -- very charismatic, like virtually all New Zealand parrots.

Tui -- another famous New Zealand endemic

Tui threat display

New Zealand Bellbird

South Island robin (This male was very confiding, foraging almost underfoot. That's always very likeable.)

January 17, 2026: Today, we boarded our Aurora ship and set sail southward.

This is our Aurora ship, the Douglas Mawson, photographed off Ross Island in the Ross Sea of Antarctica on Thursday, January 29, 2026. The ship is named after Sir Douglas Mawson, an Australian member of Robert Shackleton's 1907-1909 British Antarctic "Nimrod" Expedition (see the account of January 28). Our cabin is outlined by the red rectangle: it is conveniently on Deck 4, close to the water, where many birds fly. It is only 4 doors away from the entrance to the "mud room", where one prepares for zodiac rides and shore landings. Aurora's ships the Douglas Mawson, the Sylvia Earle, and the Greg Mortimer -- on which we sailed, respectively, now, to Iceland/Svalbard in 2024, and to Antarctica for the first time in 2022 -- have essentially identical deck plans. We stayed in this cabin 429 during all three trips and feel very much at home there. And very comfortable.

January 18, 2026: Pelagic Birding on the Way from Dunedin to the Auckland Islands

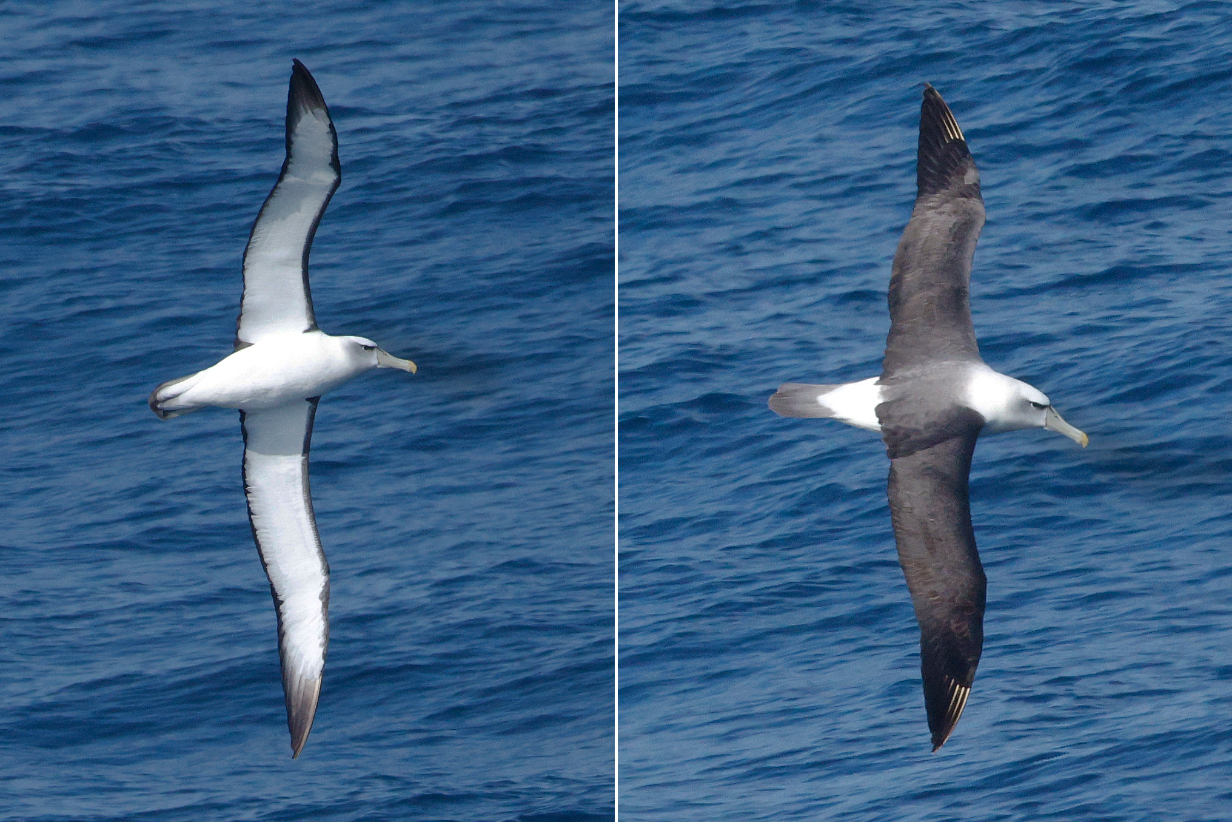

White-capped (formerly "Shy") albatross

Salvin's albatross (We saw in much better during our 2011 birding tour to New Zealand.)

White-chinned petrel (not a very good picture of a bird we first saw long ago on a Cape of Good Hope pelagic)

January 19, 2026: Enderby Island at Auckland Islands

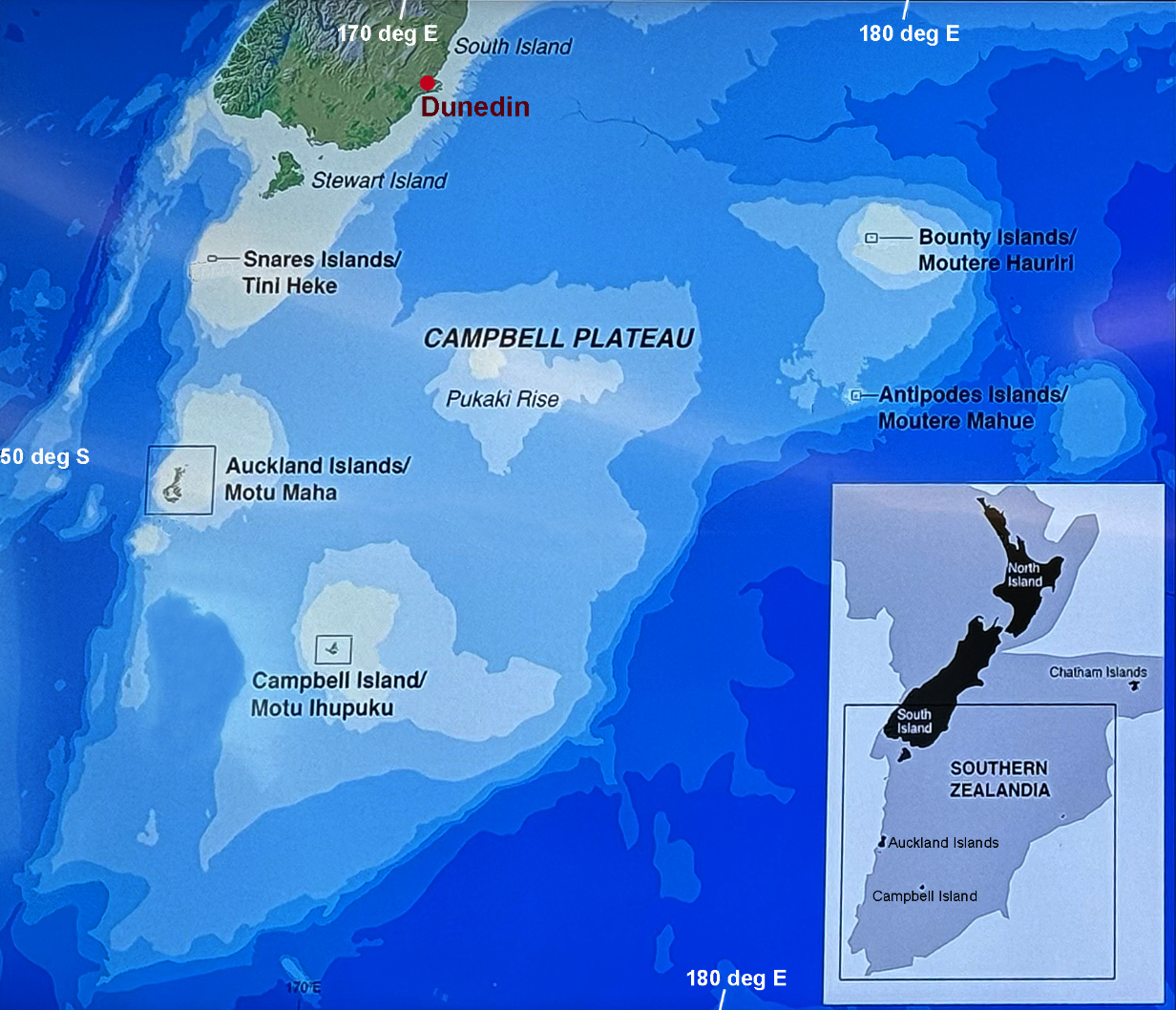

These maps put into perspective our first 2 destinations -- New Zealand subantarctic islands:

Ocean depth countours show that there is an undersea "subcontinent", South Zealandia; its plateau is typically 1 - 2 km below sea level. The surrounding abyssal plain is 4 - 5 km below sea level. Besides islands, the Pukaki Rise reaches up to about 0.5 km below sea level. So this "subcontinent" is not "in the same league" as true continents, the nearest of which is Australia. On the otherhand, Zealandia includes the North and South Islands of New Zealand and, among others, the Auckland Islands and Campbell Island. The latter were our first destinations.

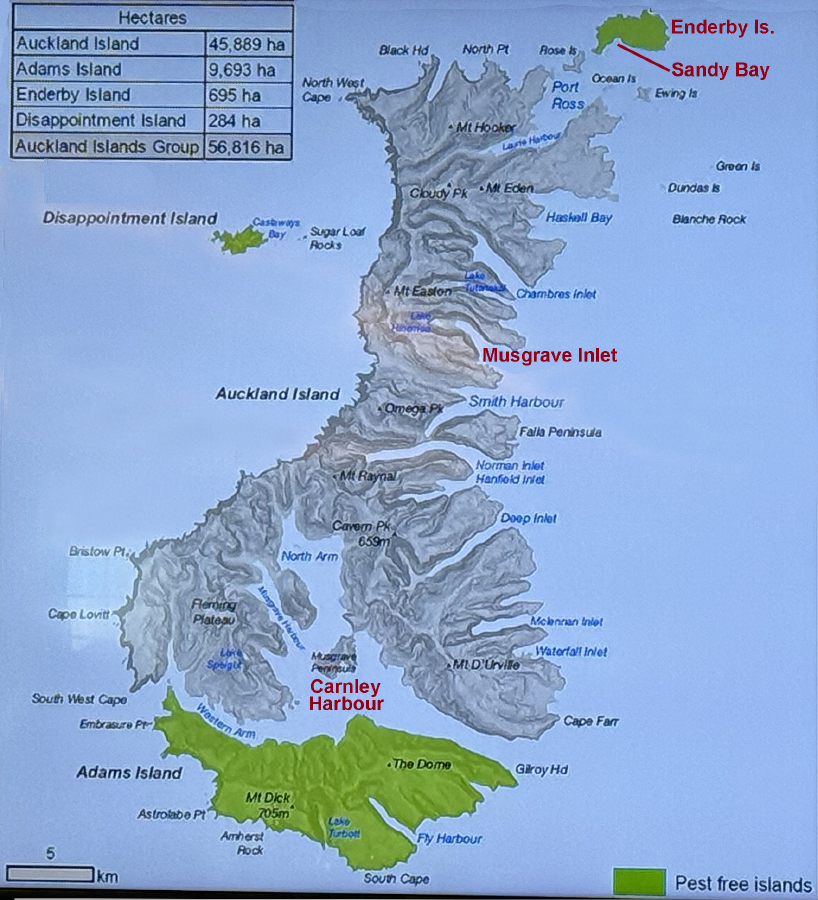

The Auckland Islands are remnants of 2 Miocene basaltic volcanoes formed 12-23 million years ago. They have since been heavily eroded by glaciers into a series of fjords. The islands include several that have always been predator-free or that have had predators such as rats and mice, feral cats, stoats, et various c. eradicated. Very strict security protocols are necessary for visitors to be able to get to these islands without importing either new predators or alien plants and diseases. Our first stop on January 19 was Enderby Island, with a landing at Sandy Bay, a hike north across the island, and later a zodiac ride. I (John) was temporarily ill and could not participate. I therefore missed Auckland Islands teal, although Mary and I both easily got Auckland Islands Shag from our ship's balcony.

Auckland Island shag -- John's second new bird of the trip -- at Sandy Bay, Enderby Island

Sea cave and cliff around the outside of Sandy Bay. Auckland Is. teal turned out to have been feeding in small numbers in the kelp ... but I was not lucky enough to spot one from the ship.

January 20, 2026: Auckland Islands:

This morning began with a wonderful zodiac cruise at Musgrave inlet (see the above map). Our zodiac driver was expedition leader Roger Kirkwood, who is calm and experienced and who runs an exceedingly enjoyable ride. The weather could not have been more perfect, with calm seas and bright sunlight. We began with a tour around cliffs with penguins:

Eastern Rockhopper penguins at the start of the AM zodiac ride. We had seen penguin shapes from the ship, but this was my first good look. So these are my life birds -- 3rd of the trip.

There were many Eastern Rockhopper penguins all along the cliffs.

Not for nothing are they called "Rockhoppers": This is the same bird, photographed twice just a few seconds apart. They are astonishingly good at rock climbing, even without arms and hands.

Eastern Rockhopper penguin. It is always a delight to see a new penguin.

In your face!

Brown skua on the cliff face, not far from (some-time) prey

Light-mantled albatross on nest, high on the cliff

Auckland Island shag, now very well seen in bright sunlight during the second part of our AM zodiac cruise on the other side of Musgrave inlet

New Zealand pipit, my 4th life bird of the trip. It is surprising that we did not see it during our 2011 birding tour of New Zealand, because it is very wide-spread. But I saw it twice in the subantarctic islands, once here and again tomorrow at Campbell Island.

Later, we here approach an archway opening to an open-roofed "cave", one of two. (The other was closed and dark inside, possibly a lava tube; I do not include pix.)

Open-roofed cave interior

Open-roofed cave interior panorama (scroll right to see it all)

Vertical panorama from inside the open-roofed cave looking out the entrance

Here is a brief movie as we emerge from the above open-roofed cave.

This afternoon, I had the decidedly mixed experience of the "zodiac cruise from hell" at Camley Harbour (see the above map). The zodiac captain was a "cowboy" who thrived on adventurous driving. Once we get well into the "Western Arm" of the bay as shown on the map, the ride got very rough and yet also very fast. I did not know that this was coming. A disadvantage of Aurora excursions is that we are often not told what to expect, so that wondrous surprises await us ... or unpleasant threats. I took only the bird camera, which was a mistake: there were essentially no birds -- in particular: no chance for Auckland Islands teal -- and I had to protect the camera throughout the ride from splashing water. And I made the personal mistake of forgetting to bring my iphone. So the good aspect of the trip could not be photographed. Once we got near the west corner of the "Western Arm", there were deep sea cliffs though the headland and out to the open ocean. We cruised part way into these, and they were worth seeing. But I could not photograph them. Had I known how physically demanding the ride would be, I would have skipped it. My back felt wrecked and my arm strength was challenged. The mostly young and robust passengers typical in New Zealand had a great time.

January 21, 2026: Campbell Island

We spent today at Campbell Island, in relatively calm seas and temperatures just about 50 degrees F. The wind was almost calm in the morning but brisk and increasingly cold in the PM. The morning zodiac ride was along dramatic cliffs to from our "anchorage" to the north end of the island, concentrating on sea caves, remarkably beautiful and artistic rock layers, birds -- including two life birds -- and the nesting colony of almost all of the world's Campbell Island subspecies of Black-browed albatross. Our zodiac driver was Howard Whelan, who is one of the most experienced crew members -- he was Expedition Leader on our Iceland/Svalbard cruise. He provided a sensitive and nuanced cruise experience.

The AM cruise traced to cliffs along the NE corner of Campbell Island to North Cape. Campbell Black-browed Albatross (Thalassarche melanophris impavida) -- a subspecies of the Black-browed Albatross breeding solely on Campbell Island, New Zealand. It is easily recognized by its pale yellow eyes (versus dark eyes in other populations), as shown later in these web pages. The picture above was taken near the start of the cruise and shows one of the many sea "cave" holes or arches; we did not approach this one.

A true sea arch a little farther along the cruise

Campbell Island shag was the easy new bird today -- ubiquitous. Like Auckland Island shag, it has a white stripe along the upper wing. It has only a white throat patch separated from the white belly by black, unlike Auckland Island shag, which is white from throat to belly. The face is also more brightly colored. See also in PM zodiac ride pictures, below.

Antarctic tern in breeding plumage

This is a true sea cave somewhat more than 100 feet deep before it dead ends. It was easy and interesting to enter ... and to contemplate the violent storms that must sometimes happen for waves to have dug this feature. Today, in calm seas, there was only a thin splash line of drops from the cliff above.

Interior end of the sea cave: The red algae on the walls indicates that we are near low tide. Scroll right to see the complete panorama.

Campbell Island albatross nesting groups started to get more numerous as we sailed farther north along the cliffs.

Waterfall

Campbell Island shags in a prominent layer of red rock that ran from here all the way to the north end of the island. Its many twists created another 3-D art display that captured me in the same way as eroded rocks captured me artistically in the Kimberley region of Australia during our July-November 2025 Seabourn cruise from Darwin, Australia to Santiago, Chile. The following pictures are an art gallery of this red rock layer. An important point of the above picture is to use the shags to provide a sense of scale.

Artistry of the red rock layer

Erect-crested penguin (This is my life bird -- the 6th of the trip and 2nd penguin)

Campbell Island albatross (Thalassarche melanophris impavida) is a subspecies of Black-browed albatross (Thalassarche melanophris), which we have seen world-wide (off the Cape of Good Hope, in subantarctic waters off Ushuaia and the Falkland Islands, and around tropical Pacific islands). They breed only here, at Campbell Island, with >~ 24,000 breeding pairs according to Wikipedia. I saw many clusters of breeding nests all along this zodiac cruise.

Campbell Island (Black-browed) albatross nesting grounds, with startlingly light-eyed adults and fluffy chicks

I insert this picture here, out of sequence, to show what the bird looks like when it poses conveniently beside our cabin's balcony, at lunch time, between AM and PM zodiac cruises.

North Cape panorama (scroll right to see it all) Note the curvy red rock layer, which figures prominently in the 3-D art pictures above.

Another panorama a little farther around North Cape. With zodiac driver Howard Whelan.

Closer-up view of the rugged cliffs around North Cape, with sea alcoves and caves and the remarkable warped layer of red rock. Campbell Island albatrosses nest high up above the cliffs but are not visible here. This is roughly where we turned around and headed back south to the ship.

One more closeup view of the rugged cliffs and sea caves near North Cape

In the afternoon, the ship stopped at (dead calm) Perseverance Harbor. Most people took a hike of up to about 7 miles round trip, up the hills from the landing to see Royal Albatross nesting up close. I told the shore crew that I was mostly interested in seeing what would be my 3rd new bird of the day, the flightless Campbell Island teal. They were kind enough to arrange a private zodiac ride along both sides of the fjord. I am exceedingly grateful to my cheerful and dedicated Russian guide, Ivan Klochkov,who had seen the bird here on his last voyage a few weeks ago and who tried hard to find one for me. We did not succeed, although the zodiac ride was very enjoyable and we saw a good number of other birds. Eventually, it started to rain; I got cold, and we gave up.

During lunch time, the ship was repositioned in Perseverance Harbor. Along the way, we saw hundreds of Sooty shearwaters in great flocks, congregating -- we assume -- in spots along the fjord where there is lots of food. They never came close, but they were unmistakeable.

Southern giant petrel juvenile

Campbell Island shag: The relatively sheltered Perseverance Harbor is a good place to raise young. This is a juvenile.

Campbell Island shag -- adult in breeding plumage

Kelp gull is the ubiquitous gull here.

Campbell Island carrot (Anisotome latifolia) is a beautiful megaherb that contributes wonderfully to the wild and beautiful scenery.

New Zealand pipit at work -- last bird of the PM zodiac cruise before rain set in

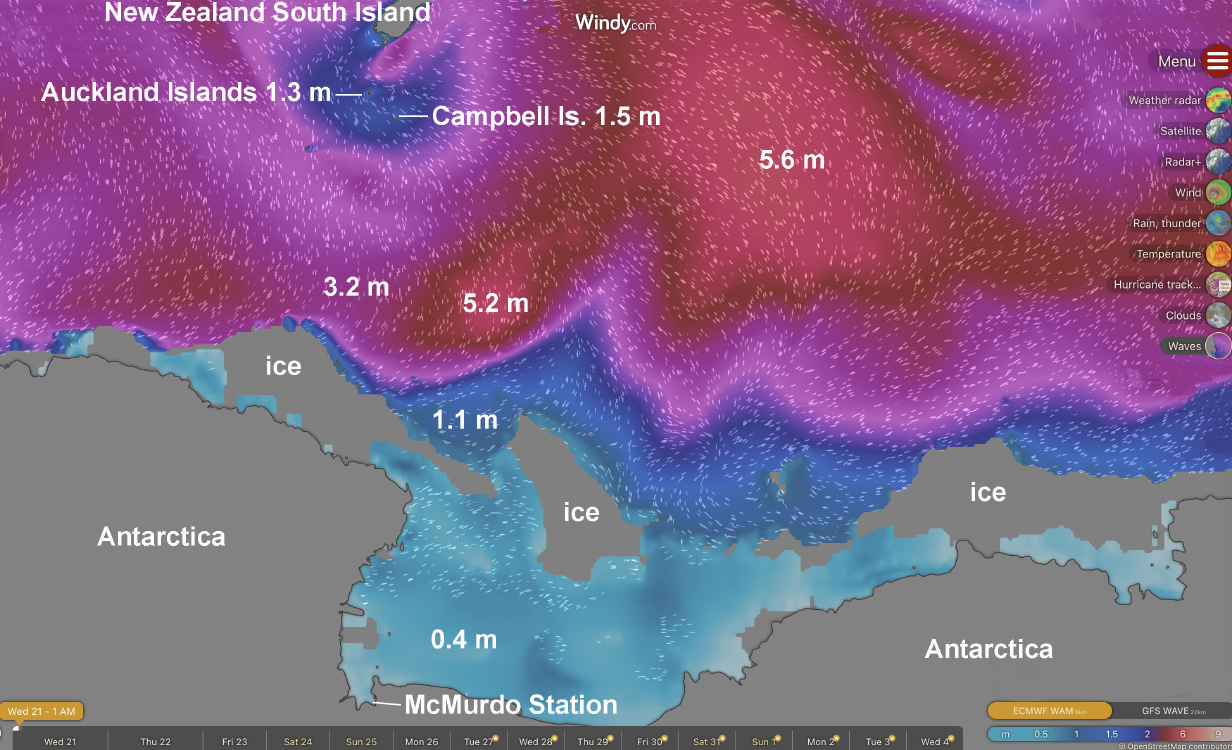

The following 4 days were scheduled for the run south from Campbell Island to the Ross Sea. The above Windy Waves map shows the situation during the evening of January 21. The numbers give the heights of typical swells in meters. So far, we have been remarkably lucky to have easy seas (blue in the map). Seas continued to be fairly favorable all the way to Antarctica: as the weather moves eastward (i. e., to the right), it looked like we would have a "window of opportunity" with wave swells not much bigger than 10 feet along the way. In the event, weather changed more quickly than this map might suggest ... although, as I write this on January 24th, most of the way to the Ross Sea, we continued to have moderate seas. We had only a brief period of roughly 10-foot swells this morning, and now (4 PM) conditions have eased again. All this is in part good luck and in part good planning by Aurora: They know how to juggle our schedule to take advantages of easy seas. Of course, we still need to sail back north from Antarctica to New Zealand. Nobody can predict what conditions will be like. But we trust Aurora to keep conditions as comfortable as possible for us all.

January 22, 2026: At Sea

January 23, 2026: At Sea

January 24, 2026: At Sea

Today was another sea day, starting out in adventurous waters, with sea swells in excess of -- I would guess -- 3-4 m but calming a lot by the end of the day. We crossed the Antarctic circle at 6 PM and should now not see another sunset for more than a week. We will see ... but we should reach latitude 77 degrees 50 minutes south at McMurdo Station. This is almost as far south as our northernmost point was north -- just over 81 degrees N latitude in Svalbard in 2024. But of course, conditions will be more extreme here, because Antarctica is "continentally cold", whereas Svalbard -- like all of northern Europe -- feels some effects from the Gulf Stream warm ocean current. And because the North Pole is under an open ocean, not under a continent with typical ice sheet elevation of ~ 2500 m = 8200 feet.

Antarctic petrel was the very easy first bird of the day. This is my 7th life bird of the trip. It flew around our (starboard) side of the ship repeatedly, giving me great looks. These are all pictures of the same bird.

Light-mantled albatross (This morning was the second-last day that I saw one, as we sailed south.)

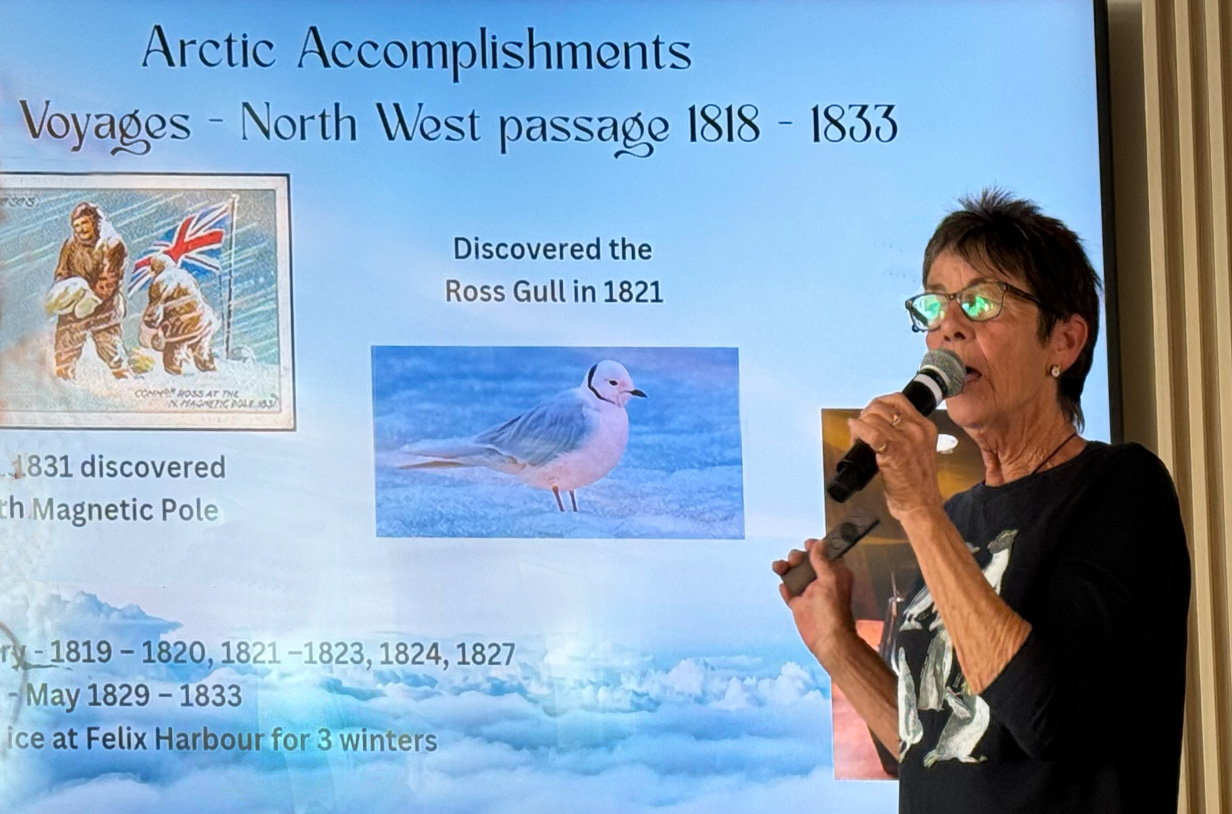

An honored guest on this voyage is Ms. Philippa Ross, the great, great, great granddaughter of Sir James Clark Ross, who discovered Earth's North magnetic pole in 1831 and the Ross Sea region in Antarctica in 1841. Today, she gave us a fascinating account of his life and accomplishments. One tidbit that I had missed -- but should not have missed -- is that he also discovered Ross's gull. It is a far-northern gull that few birders get to see. But I had the good fortune to see one -- as did my mother -- about 25 years ago, when it showed up as a very rare stray at Point Pelee National Park. A great crush of eager birders rushed to the south-pointing sand spit at Point Pelee to see one slightly pink-headed gull with black collar hiding among many other birds. I have cherished that sighting for many years ... having no idea that I would one day head far south to visit the Ross Sea and, along the way, have the privilege to meet Philippa Ross. She is an energetic and outspoken naturalist, environmentalist, and self-dsescribed enthusiologist and human ecologist.

January 25, 2026: At Sea

We were still at sea all day, reaching into the Ross Sea by evening. I did some pelagic birding twice for about 1/2 hour each, but the temperature was several degrees below freezing; the wind was brisk, and it felt very cold. Still, I got one life bird almost first thing in the morning:

Mottled petrel (This not very good picture is my life bird, identified instantly by the ship's bird expert AK. I saw at least one more -- this time easily recognized by me -- during the 11 AM bird count (see below). Mottled petrel is my 8th new bird of the trip.

Mottled petrel from Deck 7, about an hour later. Again, I found it myself and this time, I also identified it myself. Happily, it is an easy bird to recognize, even far away.

Southern fulmars suddenly got common -- old friends from previous trips to Antarctica

Snow petrels are beautiful, not very common or easy to see, and hard to photograph. So far, this is the best that I could do.

Southern giant petrel is gigantic ... and also hard to photograph when it is so dark.

January 26, 2026: Cape Adare, Antarctica

Much of today was still spent at sea, sailing mostly westward after detouring somewhat east to take advantage of an opening in the pack ice that still partly blocks off the Ross Sea from the ocean farther north. That pack ice helps us a lot, because it blocks big ocean swells and results in very gentle ~ 1 m swells in the Ross Sea. We arrived at Cape Adare in mid-afternoon ... only to find that local ice floes made landing harder than expected. I had spent quite a lot of time outside in several-degrees-below-freezing cold, so I skipped the landings. All of the following scenery and bird pictures were taken from the balcony of our suite.

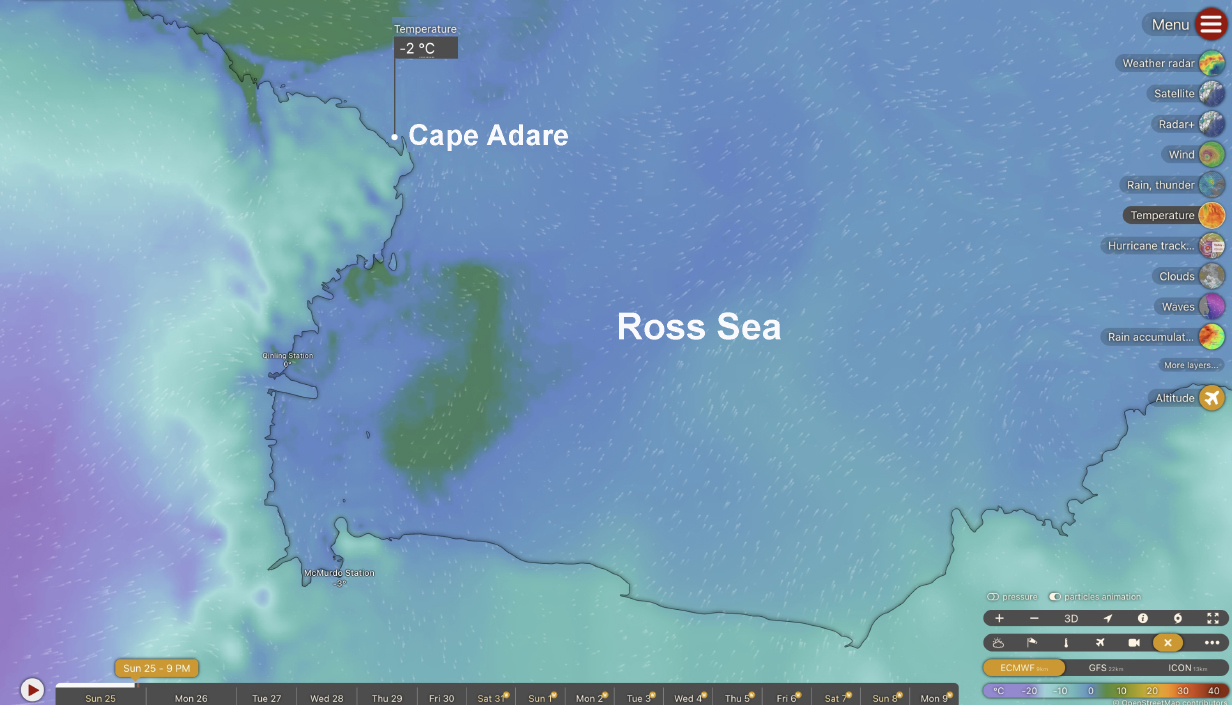

Windy Waves map of temperatures in the Ross Sea on the morning of January 26. (My laptop's clock is still set to American CST.) The location where the ship was parked for shore excursions is marked with the white dot at the bottom of the temperature flag.

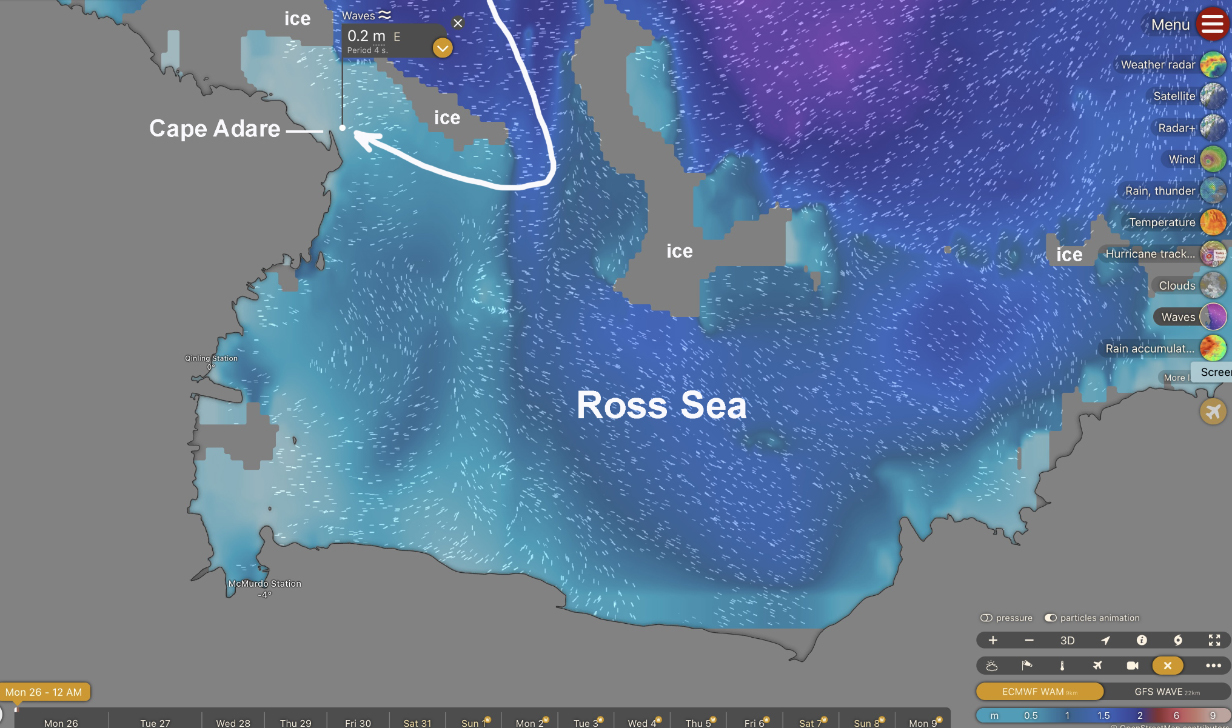

Windy Waves map of sea swell heights during the evening landings on January 26th. The white line with arrow at the end shows how we detoured around sea ice to get to Cape Adare. Situational awareness is critical to having a good trip to Antarctica, and Aurora crew are masters of it. In the coming days, we will sail down the western shore of the Ross Sea as far as McMurdo Station.

Expedition Leader Roger Kirkwood briefs us on the shore excursions at Cape Adare. The ship is positioned inside the bay that separates the cape from the rest of the mainland. Most of Cape Adare penninsula is steeply mountainous, but a triangle of sand about 1 km on a side was our destination: About 300,000 pairs of Adelie penguins nest there and on up the slopes. This is the biggest Adelie nesting colony in the world. Also on that triangle is the (restored) "Borchgrevink's Hut" from the British Antarctic expedition of 1898-1900. The hut is shown in some pictures below. Google AI notes that "it is the first, oldest, and only surviving example of humanity's first building on any continent." Since the closest side of the sand triangle is much closer to the ship than the far side or the farther hills, the nearest penguins in the pictures that follow look markedly bigger than the farthest ones.

Antarctic petrel in the morning, many hours before we got to Cape Adare.

South Polar Skua, approaching Cape Adare, where there was abundant prey ... at least when Adelie penguin chicks were still smaller

Southern giant petrel, ditto

Cape Adare panorama from our suite's deck. Scroll right to see it all.

Cape Adare -- Borchgrevink's Hut is in the middle of the picture.

Borchgrevink's Hut and Adelie penguins.

These pictures show just a few of the 300,000 pairs of Adelie penguins that nest at Cape Adare. It is late in the nesting season, so chicks are now dark brown fluffballs almost as big as their parents. They can be seen in some of the pictures. The last two pictures are enlarged panoramas: scroll right to see the whole picture. In the second = last panorama, a South Polar Skua sits in front of a high block of ice relatively near to the left end of the picture: you can see that it is not a lot smaller than an adult penguin.

The birds on the shore were too far away, but closer birds such as this one were as close as the birds that were my life bird -- also on an ice floe -- in penninsular Antarctica during our 2022 VENT bird tour with Aurora. That happened late enough in the evening so that Mary was asleep. Now, she got Adelie penguin as her 4th life bird of the trip.

Adelies porpoising! Or maybe we should say that we have seen porpoises penguining. Anyway, they did this a lot, all around the ship during landings and elsewhere and elsewhen, for lots of reasons: at least to get a good breath of air, to see around them, perhaps -- in other circumstances -- to avoid and confuse predators, and just to have fun. So what is this gigantic ... thing ... that brings so many ... people ... including that dude taking pictures (wuzzat?) on the (what shall we call it?) balcony?

Note that they almost always have their beaks open when they ..... penguin.

In the evening after supper, we started to sail away, first north and east to get past Cape Adare and then southward toward McMurdo Station. Close to the coast, we started to pass icebergs that put on a 3-D art show of their own. I will include only a few in these pages, starting with the one above.

Emperor penguin ! This is my 9th life bird and surely the most wanted bird of the trip. It was a substantial jackpot to see it on an ice floe about 15 minutes after we passed the above iceberg. It was announced from the ship's loudspeakers: "This may be the only one that we see during the trip ... or it could be one of thousands." Safest to see it early, and a delight to discover it on my own, before it was announced.

A lone Adelie penguin in the vastness of sea and ice

Actually, it was far from the only one. I say maybe 50 Adelies, some single or in pairs and others in groups of a dozen or more, on many different icebergs, as we sailed farther out into the Ross Sea.

More Adelie penguins on ice floes and ice bergs

January 27, 2026: At Sea Sailing South Along the West Coast of the Ross Sea, Antarctica

January 28, 2026: Cape Royds and Cape Evans, Ross Island, Antarctica

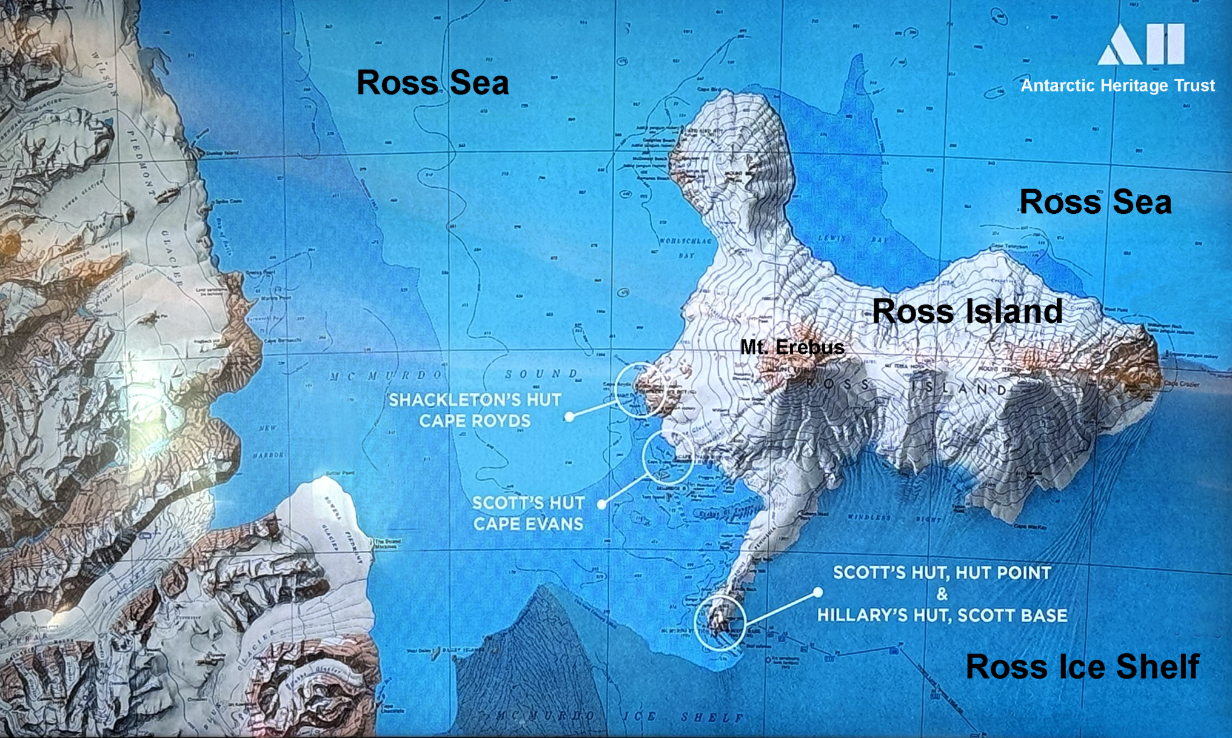

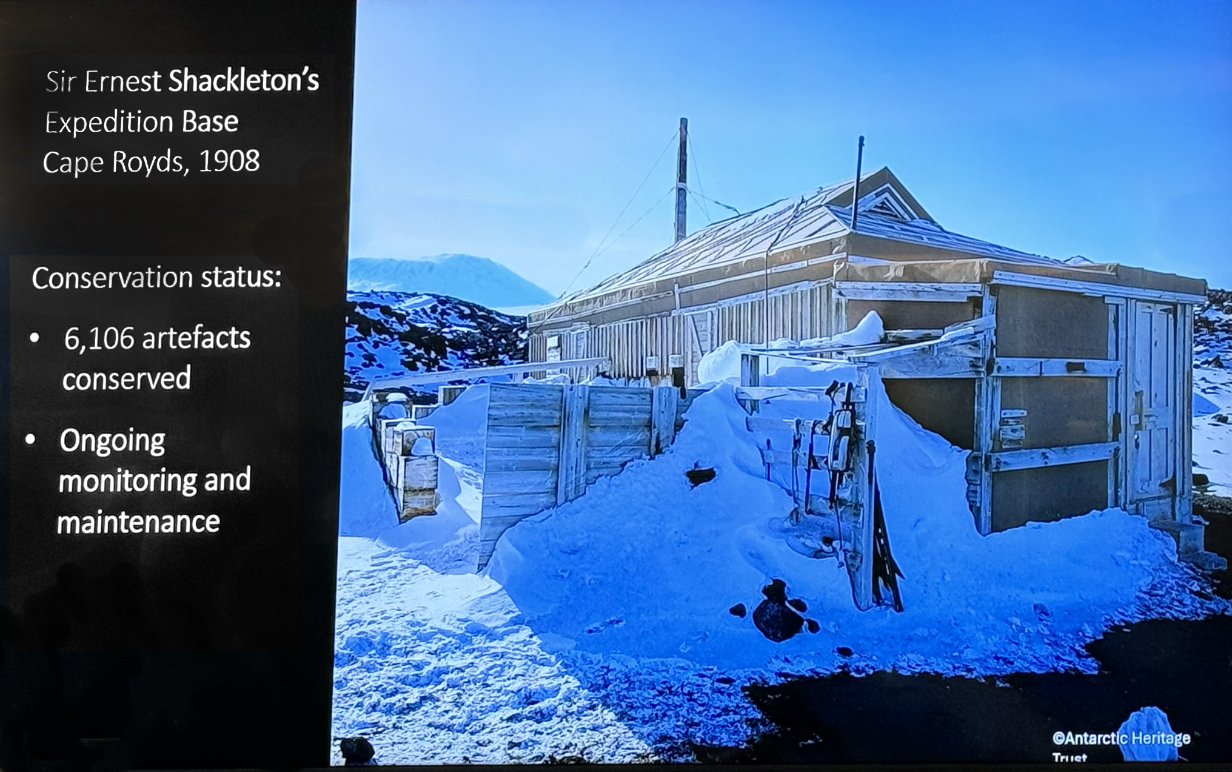

Today, we made two stops at Ross Island in the SW corner of the Ross Sea. The purpose was to allow visits to the Shackleton and Scott huts, used by those respective teams for overwinter stops. Dominating the island physically and this web site psychologically is the active volcano Mt. Erebus. This map was shown at ship's briefings and comes from the Antarctic Heritage Trust, which oversees the restoration of and safe visits to the huts and other historic and natural sites in the area.

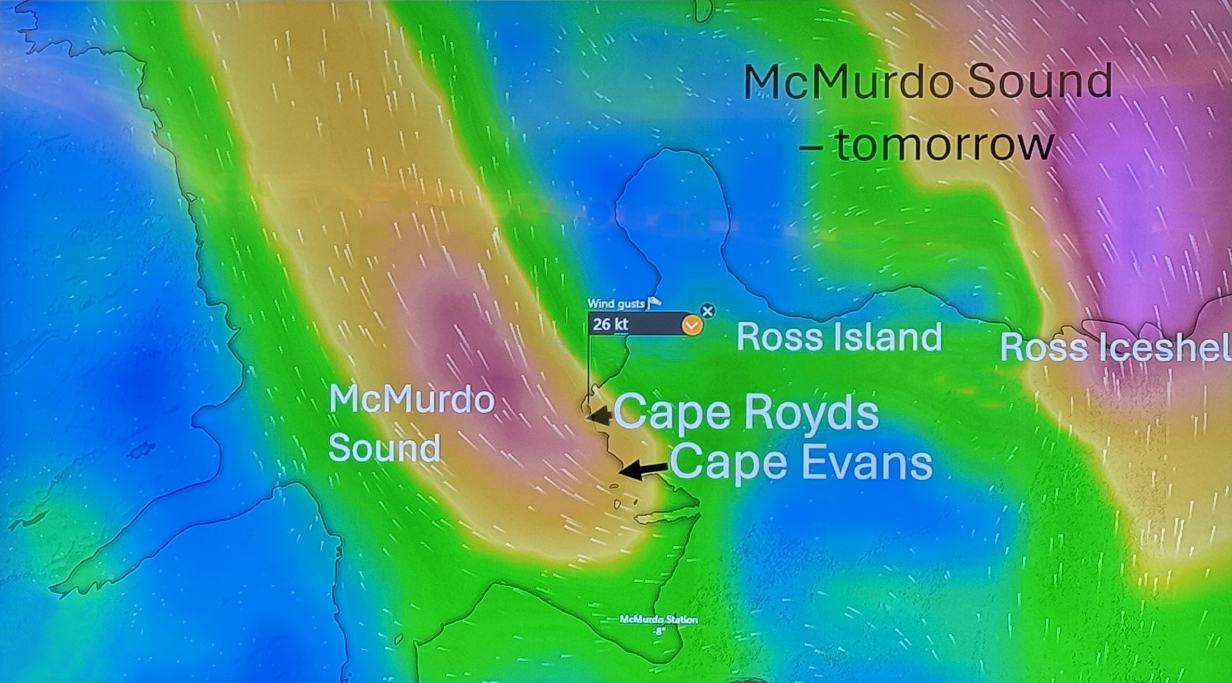

Here's the problem with today's landings: The rules for protecting historic sites in Antarctica are necessarily strict. They and weather conditions together created a situation that was dangerous for me. Today was forecast to have significant katabatic winds off the continental ice sheet; last night's Windy.com prediction (above) was for 26 knot winds at the Shackleton and Scott hut sites. The temperature was expected to be about -3 to -5 degrees C. Wind chills would be substantial. And there are rules that there cannot be more than ~ 40 people in the protected areas at a time, and only 8 people are allowed in a hut at one time. The ship budgeted about 8 minutes to see a hut. Last night's prediction therefore was that one person who visited one hut would spend about 1.5 hours doing each landing. Given the above conditions and the fact that I was already fighting a cold (with reasonable success in normal freezing conditions and with 1/2 hour outside at a time), I thought that I should not attempt today's landings.

Landing site for the Shackleton hut excursion

In the event, conditions proved to be both worse and better than predicted. The wind was a little less bad, maybe 15 knots -- still brisk. But ice forced us to land rather far from the Shackleton hut. When ship's crew estimate the walk as 1/2 hour for hardy Australians, I am sure that it would take longer for me. It looked to be more than a mile, up over the ridge shown above. Moreover, the walk was very exposed, up an unprotected slope facing the wind. (South is to the right, in the above picture.) So I skipped this landing as unsafe ... even though I have retraced bits of Shackleton's expeditions in previous trips and would have liked to see this early stop. A few published pictures (not mine!) are shown below for completeness. I meanwhile concentrated on the natural scenery, which tends to be my main interest anyway. And that was dominated by Mt. Erebus, below.

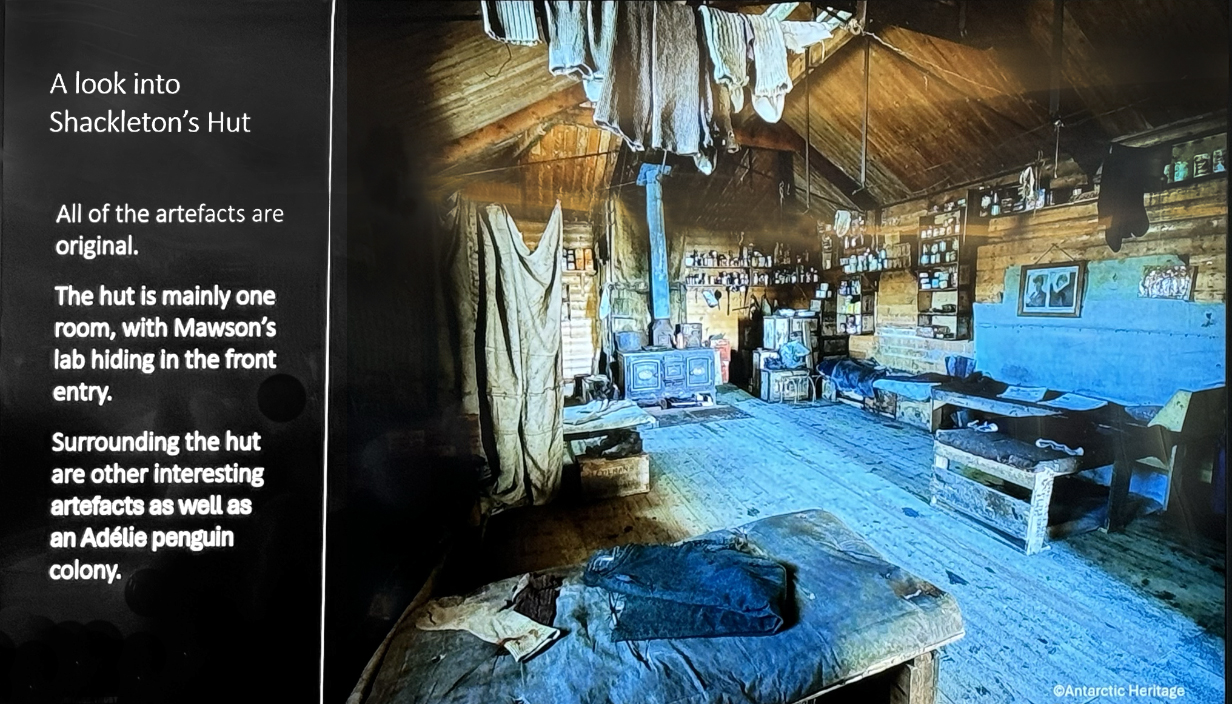

AntarcticHeritage Trust pictures of Shackleton's hut as presented during ship briefings

One more detail is worth emphasis: From this web site, these are the first 3 listed members of the 1907-1909 British Antarctic "Nimrod" Expedition. Led by Ernest Shackleton, it aimed to be the first to reach the South Pole. They fell 97 nautical miles short but set a new "farthest south" record at latitude 88° 23' S. They used the Shackleton hut as their base. They discovered the route up the Beardmore Glacier onto the Antarctic ice plateau. Douglas Mawson was among those who reached the South Magnetic Pole and made the first ascent of Mt. Erebus. Our Aurora ship is named in honor of Douglas Mawson.

Mount Erebus backlit by morning sunlight as seen from Cape Royds, Ross Island. Mt. Erebus is the southernmost active volcano on Earth and puffed gently all day. Wikipedia tells us that it is 3,792 meters = 12,441 ft high. Erebus is the second most prominent mountain in Antarctica after the Vinson Massif, 4,892 meters = 16,050 ft high, far away, inland of the Antarctic penninsula. It is the second-highest volcano in Antarctica after the dormant Mount Sidley. It is the highest point on Ross Island, which also has 3 three inactive volcanoes: Mount Terror, Mount Bird, and Mount Terra Nova. Mt. Erebus is a "polygenetic stratovolcano"; i. e., the bottom half is a shield volcano and the top half is a stratocone. Note how the upper part of the mountain has substantially steeper slopes than the shield volcano of (e. g.) Mauna Loa and is more like the explosive volcanoes Mt. St. Helens (before its 1980 eruption) and Mt. Rainier. Erebus has a 500 m to 600 m wide and 100 m deep summit caldera including a persistent lava lake ~ 250 m across. Characteristic eruptions are Strombolian, from the lava lake or from subsidiary vents in the volcano's inner crater. Today's puffing was mild.

The bird, inevitably, is a South Polar Skua.

It probably didn't feel so mild from close up.

Looks like there were a few bigger bangs ...

Mt. Erebus in afternoon sunlight, now from Cape Evans. Scroll right to see the full panorama.

January 29, 2026: Cape Bird, Ross Island, Antarctica

Today, I took a cold (~26° F), windy, and somewhat rough "birding zodiac" ride around Cape Bird at the NW corner of Ross Island. We say only 3 species, one distant Emperor penguin (no usable picture), a dozen or so South Polar Skuas, and some thousands of Adelie penguins ... some of them as close as 20-30 feet ("porpoising" in the water).

Adelie chicks in different stages of moult to adult plumage. Ogden Nash said, "When they're moulting, they're pretty revolting." Actually, they are seriously cute.

Three Adelies -- two adults and a juvenile, in the back, who has not finished moulting his "cap"

Thousands of Adelie penguins in this breeding colony. Note the creche of young birds in the middle distance: they have not yet moulted from their brown downy feathers into adult "tuxedo" plumage.

As we continued to zodiac our way around the north end of Ross Island, we started to approach the Ross Ice Shelf and the Adelie colony gave way to (here: pretty fragmented) glacier. At this point, the zodiac ride ended and we headed back toward the ship. One the way, one more surprise delighted us, close up:

Adelie penguins were sometimes all around us, giving fleeting, great views. It is not easy to focus on and photograph a penguin that erupts out of the water in places and at times that are hard to predict and surely for less than a second. Hard, but satisfying, when -- once in a while -- it works.

Our bird pictures from around the world follow standard ecozones approximately but not exactly:

Birds from the USA and Canada: our house, Hornsby Bend and greater Austin, Texas, California, Hawaii, Canada,

Neotropic birds from Central America and the Caribbean: Honduras, Costa Rica, Panama, Trinidad and Tobago

Neotropic birds from South America: Ecuador, Ecuador 2017, Brazil.

Western palearctic birds: Europe: Germany, Finland, Norway, Europe: United Kingdom, Europe: Spain, the Canary Islands, Europe: Lesbos, Greece, Israel

Eastern palearctic birds: China

Birds from Africa: The Gambia, South Africa

Indo-Malayan birds from India: North-west (Delhi, Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand) India: North-east (Assam, Arunachal Pradesh, Meghalaya) India: Central (Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh)

Birds from Australia, New Zealand.

For our 2014 December trip to India, see this travelog.

For our 2016 May-June trip to India, see this travelog.

For our 2017 April trip to High Island, Texas, see this web site.

For our 2018 March trip to India, see this travelog.

For our 2018 May trip to China, see this travelog.

For our 2018 October trip from Munich to Budapest, Hungary see this travelog.

For our 2018 November trip to China, see this travelog.

For our 2019 April trip to High Island, Texas, see this web site.

For our 2019 July trip to China, see this travelog.

For our 2021 April trip to High Island, Texas, see this web site.

For the 2021 August 3 & 4 migration of Purple martins through Austin, see this web site.

For our 2021 December trip to Ecuador, see this web site.

For our 2022 January-February trip to Peru, see this web site.

For our 2022 July/August trip to Australia and Papua New Guinea, see this web site.

For our 2022 September trip to Bolivia, see this web site.

For our 2022 November-December pre-trip to Argentina (before our Antarctic cruise), see this web site.

For our 2022 November-December cruise to Antarctica, see this web site.

For our 2023 January birding in Chile, see this web site.

For our 2023 January-March cruise from Chile to Antarctica and around South America to Miami, FL, see this web site.

For our 2023 March-April birding in south Florida (after the Seabourn cruise), see this web site.

For our 2023 November-December birding to Sri Lanka, the Andaman Islands, and South India, see this web site.

For John's 2024 February-March birding in Colombia, see this web site.

For our 2024 May-June cruise from Iceland to Jan Mayen Island to and around the Svalbard Archipelago, see this web site.

For our 2024 June 25-30 stay in Paris, see this web site.

For our 2025 April 21 - May 3 trip to High Island, Texas, see the present web site.

For our 2025 July vacation and birding in Singapore, see this web site.

For our 2025 August birding in north-west Australia, see this web site.

For our 2025 August-October Seabourn cruise from Australia to Chile, see this web site.

For our 2026 January-February trip to New Zealand and 3rd cruise to Antarctica, see the present web site.