John and Mary Kormendy: Cruise to Iceland and Svalbard 2024

This web site contains the pictures from an Aurora Expeditions cruise from Iceland to and around the Svalbard archipelago, whose largest island is Spitsbergen. The Svalbard islands are part of Norway, between Norway and the North Pole at about 79 degrees north latitude and 16 degrees east longitude. The cruise lasted from May 30 to June 24, 2024. I took a computer, so some pictures were posted during the trip as I had time. Both trips are now over and we are back in Austin. This web site is essentially finished, although I might add a few more pictures.

This web site is long: it contains 328 pictures and 5 movies. Its main purpose is not so much to showcase the trip for public readers as it is to record our memories. So I include some not-very-good pictures that document details that are important to us.

Trip Birds

Ivory gull (This is my life bird, seen on June 16, 2024 at about 81 degrees N latitude. This rare and hard-to-see bird has to be my "number 1" trip bird.)

At the beginning of the trip, I felt that my "most wanted bird" was Rock ptarmigan. I got my life bird male on the first day of birding, guarding his territory from high up in a tree (see below). Next day, on 2024 May 29, we saw a male and female close up, not much more than 5 m away, in a remote wilderness of moss- and lichen-covered lava on the Snaefellsness Penninsula. They looked so wrapped up in each other -- it was mating season -- that they scarcely paid attention to us. This is the male. It is my second "trip bird".

Summary Maps

The Iceland part of the cruise started in Reykjavik, rounded the west side of the island, and then headed north-east via Jan Mayen Island (70.98 degrees north, 8.53 degrees E) to Longyearbyen, Svalbard.

The Svalbard part of the cruise had stops, zodiac excursions, and shore landings determined in part by the weather. This is not as simple as it sounds. For example, one would think -- correctly -- that storms preclude landings and zodiac excursions. What's not obvious is this: If the cloud ceiling is low enough so that scouts can not see up mountain slopes far enough to determine that no polar bears are lurking, then this is enough to preclude a landing. Throughout the Svalbard part of the trip, the most persistent focus was more on bears (which are unpredictable) than on the weather (which usually was very nice). Expedition staff and crew went to great lengths (1) to protect us from the danger of bears, (2) to protect bears from being affected by our presence, and (3) to find as many bears as possible. Often, (3) controlled the agenda.

A detailed map that shows our destinations in Svalbard is posted later in this web site.

Three Weeks of Nonstop Sunshine

From morning sunrise on June 3rd or 4th off the coast of Iceland until the evening of June 24th in Oslo, we enjoyed three weeks with the sun above the horizon. We crossed the Arctic Circle at 21:00:00 on June 3rd. But this is 18 days before the summer solstice, and I don't know whether we got far enough north on the 3rd to not have a sunset on that day. Certainly we did not have a sunset on or after June 4th until we got to Oslo. This was the second trip during which we had many days of 24-hour-per-day sunshine. We also spent 8 days far enough north in Finland and Norway in midsummer 2006. It's a unique and wonderful experience.

Map of Southwest Iceland

Google maps annotated map of the Southwest Iceland part of the trip. We flew into Keflavik airport and were taken to the Fosshotel in downtown Reykjavik. After a day of rest, John went birding on May 28 and 29. The guide was not a birder, but he had some experience with birds and worked hard to find as many species on my wish list as possible. Our drives on both days are outlined in black dots. On May 28, we circled the northern of the two penninsulas that are outlined; we got my life bird Rock ptarmigan (picture inset) at a farm at Ytri-Fagridalur. On May 29th, we circled the Snaefellsness Penninsula. Both drives benefited from the Hvalfjordhur tunnel under Hvalfjordgur Fjord -- it is 5.8 km long, goes down as far as 165 m (541 feet) below sea level, and shortens the distance to the north by 45 km = 28 miles. It saves almost an hour of driving. That was important, given that both outings were ~ 12 hours long.

On May 29th, we circled the Snaefellsnes Penninsula counterclockwise, with photo stops at several places, notably Kirkjufell (photo insert) and Arnastapi. From Arnastapi, we got a brief but good look at the 1446-m-high, glacier-covered summit of the Snaefellsjokull. On the first day of the Aurora cruise, we rounded this penninsula again; this time going clockwise. The inset picture of the summit was taken from the ship as it sailed roughly where the inset is placed in the map. That picture is shown better, below.

At around noon on May 29th, we got superb looks at a male and female Rock ptarmigan in the mountains roughly where the road crosses from the south to the north side of Snaefellsnes Penninsula. We found out later that a strong volcanic fissure eruption started at just about this time, just SE of Reykjavik and slightly NE of Grindavik. The insert picture of that eruption is centered where it happened. It dominated the news for several days and threatened to cut off the road to Grindavik. This area had erupted several times during the previous year. Fortunately, this eruption stopped after several days with no serious damage. Given our schedule, we did not get to see any of the eruption.

Despite working hard, we got only 2 life birds during the 2 days of pre-cruise birding, Rock ptarmigan (seen twice) and Glaucous gull (seen on most days of the trip, both from land in Iceland and during the cruises). I got 5 more life birds during the cruise: Ivory gull, Little auk, Great skua, King eider, and Snow bunting.

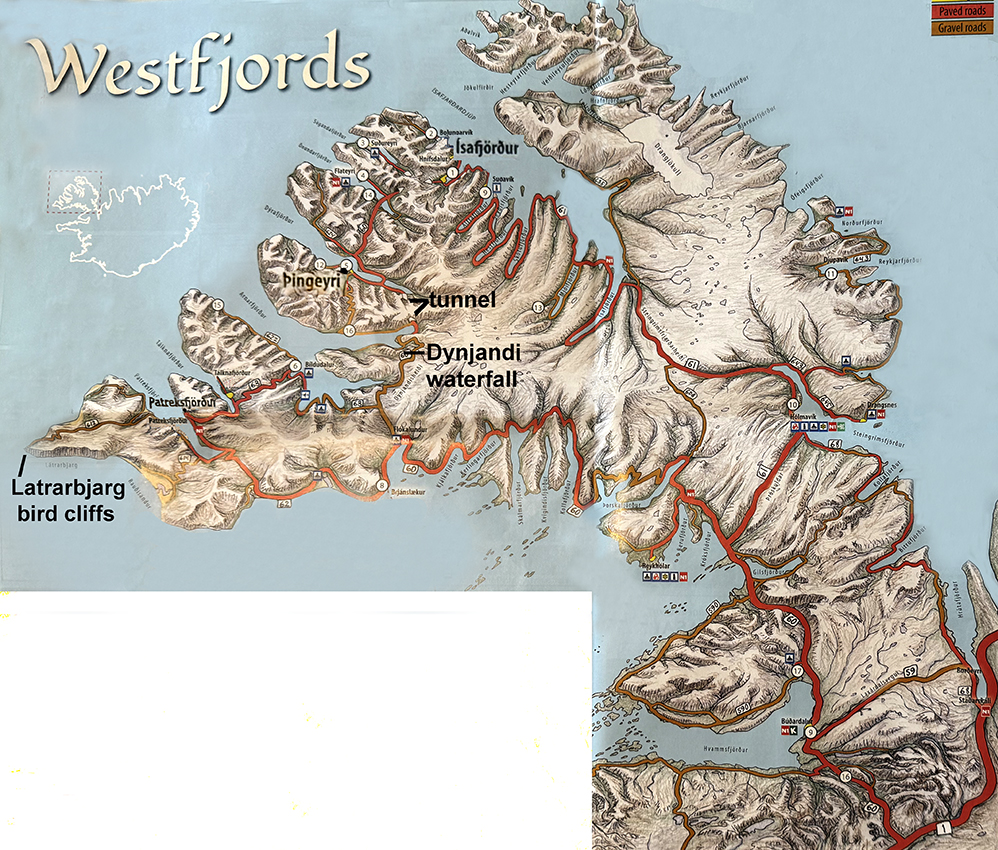

The Aurora cruise started with the "Golden Circle" bus tour: the main stops were at Thingvellir National Park, Geysir, and Gullfoss (where the two diagonal black lines intersect, just off the map). Geysir is not illustrated in this web site: it was too cold, windy, and stormy for either of us to get to the main active geyser. The other two destinations are illustrated below. The cruise then spent 2 days in Westfjords, the southern part of which is shown in the above map. The main destinations were the Latrarbjarg bird cliffs, reached by a bus drive from Patreksfjordhur, and the Dynjandi waterfall complex. Both are illustrated below. After these stops, the ship headed NE to Jan Mayen Island and Svalbard.

Birds Near Reykjavik Before the Cruise

Common snipe -- first good bird sighting of the trip

Redwing (not a very good picture ... but there is not a lot of opportunity for forest birding in Iceland, and this turdus thrush -- Turdus iliacus -- is a bird that I don't see often)

Meadow pipit (Note the long hind claw.)

Black-tailed godwit (Icelandic subspecies: Limosa limosa islandica)

Common eider male and female -- seen often

Whooper swan

Rock ptarmigan (This is my life bird on Day 1 of the trip, presumably guarding his territory in this, the mating season. Happily, this bird was known by a friend of my guide to live at Ytri-Fagridalur, at a farm whose location is shown in the SW Iceland map, above. We saw a different bird and its mate next day.

The sign for the valley and farm above had a Common snipe sitting on it!

Rock ptarmigan (male)

Rock ptarmigan (female) (Both male and female were very tolerant of us -- perhaps so involved with each other, now, in mating season that they hardly paid attention to us.)

Northern wheatear in the lava field near the ptarmigans. We were looking for Snow bunting but were unsuccessful -- they are hard to find in summer. This is the best picture of a wheatear that I've ever gotten.

Northern wheatear female -- courtship behavior?

Panorama taken at the high point (~ 250 m altitude) of the crossing (south to north) of the Snaefellsness Penninsula shortly before noon on May 29, 2024. This is very typical Icelandic scenery. Scroll right to see the full 180-degree panorama.

Kirkjufell, the iconic 463-m- = 1520-foot-high hill off the north shore of Snaefellsness Peninsua near the town of Grundafjoerdhur (my transliteration of Icelandic). Wikipedia says that "It is claimed to be the most photographed mountain in the country. Kirkjufell was one of the filming locations for Game of Thrones season 6 and 7, featuring as the 'arrowhead mountain' that the Hound and the company north of the Wall see when capturing a wight." From top to bottom, the layering records about 10 million years of history as carved by many successive glaciations. Some layers are lava, some are ash, and some are sedimentary.

Common redshank (Seen often. I actually reduced the color saturation of this image to make the bird look not too garish.)

Gull Studies: Iceland versus Glaucous Gull

The critical issue for this section is: Did I see Iceland gull? Both Iceland gull and Glaucous gull would be new on this trip. I saw Glaucous gulls many times. They were relatively easy, both in terms of size (see the first picture below) and in terms of other field marks. But did I see Iceland gull? The conclusion will be "No."

Background: ID books say that Iceland gulls are in Iceland only in winter. In summer, they fly to Greenland to breed. Still, I suspected that a few birds might stay in Iceland, in the same way that, e. g., you regularly see a few shorebirds and geese at the Salton Sea in California, even though the vast majority of these birds have flown to the arctic to breed. The problem then becomes (1) that you need to be lucky to see one of the (possibly few) Iceland gulls that are still in Iceland in summer, and (2) that you need to be especially lucky if you want to see a rare Iceland gull together with the most similar species, which is Glaucous gull. Only then can you confidently compare the two species. And it helps to compare Glaucous gulls with other species, too -- ones that are easy to identify with field marks. I often have trouble with gull IDs. This section illustrates why.

The field mark that will be a problem is size. The Svensson et al. (2023, Princeton University Press) book "Birds of Europe" lists the following size ranges:

Great black-backed gull: 61-74 cm;

Glaucous gull: 63-68 cm;

Iceland gull: 52-60 cm;

Herring gull: 52-60 cm;

Lesser black-backed gull: 48-56 cm,

Black-legged kittiwake: 37-42 cm.

So Glaucous gulls are almost the same size as Great black-backed gulls. In contrast, Iceland gulls are always smaller than Glaucous gulls -- the size ranges of these species do not overlap. And, if I believe these ranges, then Iceland gulls are the same size as Herring gulls and almost as small as Lesser black-backed gulls.

It was convenient when I was able to see several species sitting side-by-side. Let's start easy:

This is a poor picture, but here, we see a Great black-backed gull and two Glaucous gulls at almost the same distance from me. The important point is that they are almost the same size. The Glaucous gulls here are just a little smaller than the Great black-backed gull, consistent with the above size ranges. Glaucous gull was the first new bird of the trip. I saw it often.

Here is the first size problem. Herring gull is supposed always to be smaller than Glaucous gull. In the above picture, the left bird is -- I believe -- a Herring gull: it clearly has black wing tips. The right-hand bird is presumably a Glaucous gull. But it could be an Iceland gull, because both have white wing tips and white trailing edge of wings. But the wing tips when folded here project longer than the tail by only a small amount. Iceland gulls have very long wings that project far beyond the end of the tail (see below). So the right-hand bird is almost certainly a Glaucous gull. Still, it looks essentially the same size as the Herring gull, even though -- see above -- it is supposed to be bigger than a Herring gull. It looks like size is not a reliable ID field mark. Or that I don't judge it reliably.

The following pictures show why I think that field marks can send conflicting messages. These pictures are a study of 4 or 5 gull species. They fortuitously sit in a row with the biggest gulls farthest away. Here's the problem:

Farthest away here is a "text-book" Great black-backed gull. It is huge and has flesh-colored legs. Nearest is a Lesser black-backed gull, obviously much smaller and with dark yellow legs. In between is a gull with grey back and (it will turn out) white wing-tips. Note that it is intermediate in size, close to the size of Lesser black-backed gull and much smaller than Great black-backed gull. To my inexperienced eyes, it looks relatively gracile and delicate. It has a rounded head with high forehead. And it has dark pink legs. More field marks will be shown below, but based on the above -- mostly on size -- this looks a lot more like an Icelandic gull than a Glaucous gull. Aurora's bird guide, Snowy, agreed that it was an Iceland gull, when I showed him these pictures on June 4th. Our long-time "world guide", Jack Poll, was not part of this trip, but when I showed him these pictures, he confidently IDd the middle bird as Glaucous. In the end, I will accept his verdict (see below). But first:

This shows an earlier picture in a sequence that I took on 2024 May 29 in a fishing village on the north shore of Snaefellsness Peninsula. Here, a Glaucous gull is still standing just beyond the Gread black-backed gull. Glaucous gull should be bigger and more robust than Iceland gull, and this bird looks bigger than the closer, questionable gull, even though it is farther away from me. It is in fact almost as big as the (slightly closer) Great black-backed gull. So, using size as the primary field mark, I'd guess that the closer bird is an Iceland gull. The following picture clarifies and confirms this point:

When we arrived at this lucky confluence of gulls, a Black-legged kittiwake was sitting just closer to us than the Lesser black-backed gull. It was clealy much smaller and more delicate than the other 4 birds. But it quickly flew away. For completeness, I include this not-very-good picture that shows the kittiwake, too. Here, the important point again is that the second-nearest standing gull looks the same size as the Lesser black-backed gull and clearly smaller than the Great black-backed and Glaucous gulls. However:

This shows the smaller gray-backed bird above after all the other birds had flown away. It is standing with folded wings especially clearly separated from its tail. Also, fortuitously, the bill looks longer than in the above pictures: at this moment, I caught the bird with its head turned perpendicular to the line of sight. So we see the true length of the bill. And the answer is: It is very long, longer (compared to the size of the head) than Iceland gull bills should be, according to pictures posted on the web. And here's the clincher: Svensson et al. (2023) say, "As a rule, the bill [of an Iceland gull] is obviously shorter than the length of the (long) projection of primaries beyond the tail-tip" (emphasis in the original). That is clearly not true here. This field mark definitively implies that the bird is Glaucous.

In another picture of the same bird, the wings again extend beyond the tip of the tail, but not by as much as the length of the bill.

So ... it troubles me that, in my opinion, the field marks of wing length and bill length seem robustly to conflict with the implication of overall size. But Jack Poll knows both species very well. He is convinced that all of the above similar-looking birds are Glaucous. I am very grateful to Jack for his nuanced judgment. I conclude that, at best, I cannot be sure that I saw Iceland gull. More realistically, I agree that bill length and wing length are more definitive field marks than size. So I did not see Iceland gull.

I include this detailed discussion to show how careful birders have to be about difficult IDs. If you want to be confident that you believe your life list -- and I do! -- then I have to be this careful about difficult cases.

End of Gull Studies

Red-throated loon

Red-necked phalarope (breeding-plumage female)

Red-necked phalaropes mating (We were here in the perfect Spring season.)

Map of the west end of the Snaefellsness Penninsula. The 5-gull study was photographed in Olafsvik (upper right). We had lunch there. The above pictures that follow the gull study were taken at various locations around the end of the penninsula. The picture of the summit of Snaefellsjokull, below, was taken from near the west end of the penninsula; a very similar picture taken from the Sylvia Earle appears later, below, as part of the cruise. Arnastapi is at bottom-right in the map. The telephoto picture of the summit was taken from there. Both are shown below.

Snaefellsjokull from the west

Arnastapi harbor at low tide (scroll right to see the full panorma)

Snaefellsjokull summit from Arnastapi

Scenery and Pelagic Birds During Iceland Cruise

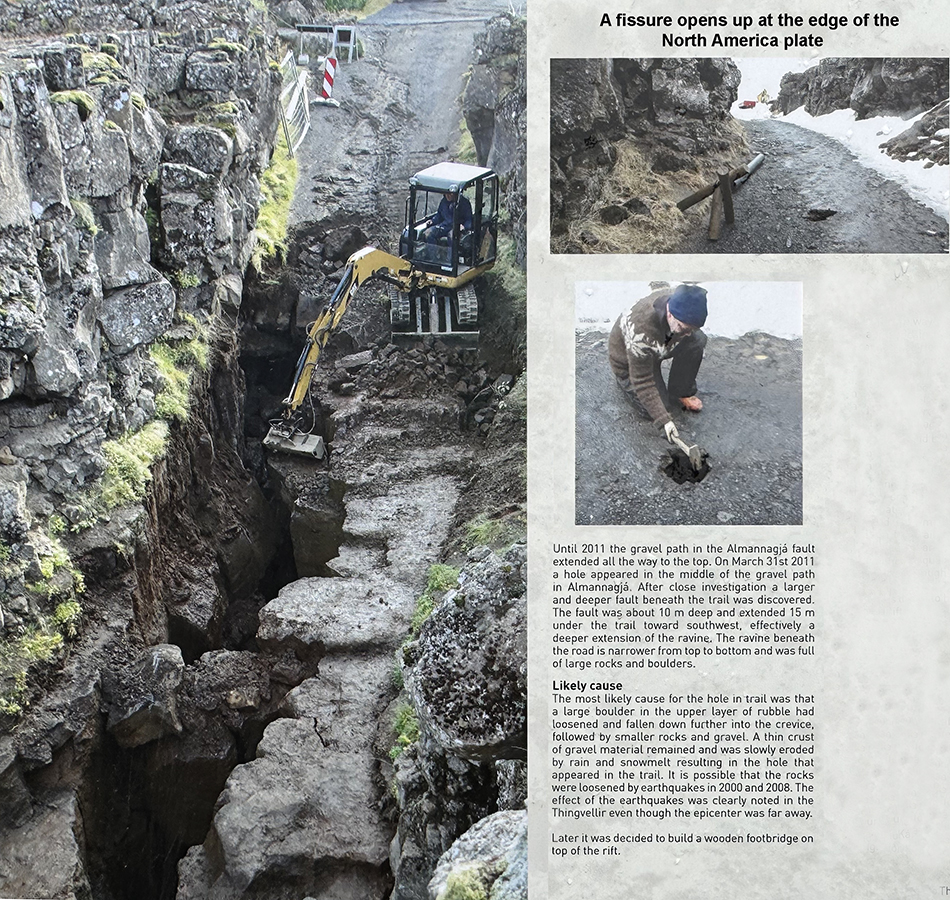

Mary at Thingvellir National Park. Behind and to the right of Mary is a subsistence valley. Mary is standing near the edge of the North America tectonic plate. The hills in the distance on the right are the Europe tectonic plate. The plates are moving apart, and the valley between them deepens by subsistence as the plates separate. It is rare to get such a clear and dramatic view of tectonic plate boundaries. Scroll right to see the complete panprama.

The fissure shown below is behind Mary.

Plate boundaries are, of course, not sharp, clean edges. Cracks form and close, sometimes quickly in earthquakes and other times more slowly via erosion and weathering. This area looked significantly different > 1000 yr ago, when it was first settled by people who came here from Scandinavia. Smaller differences are only a few years old.

This shows the fissure now, with the wooden footbridge in place.

The last stop on the "Golden Circle Tour" was the powerful Gullfoss waterfall. This sentence is redundant, because "foss" means "waterfall" in Icelandic.

At the end of the Golden Circle Tour, we were taken back to Reykjavik, where we boarded the Sylvia Earle and sailed, that night, to the middle of the south side of the Snaefellsness Penninsula.

Black-legged kittiwake is the common gull during at least the first part of our voyage.

Northern fulmar -- like a flying, stubby white torpedo with gray wings. Interestingly, Southern fulmar (see Antarctica pages) has a body shape more like a gannet, whereas Northern fulmar reminds me more of a chunky gull. This picture was taken from the balcony of our suite on 2024 June 1, south of the coast of the Snaefellsness Penninsula.

Snaefellsjoekull or Snaefells glacier from our balcony as we sailed around the end of the penninsula, northward, toward the fishing village of Grundarfjordur. The summit is at 1446 m ~ 4745 feet altitude. We drove around the end of the penninsula in the opposite direction on day 2 of the trip, looking for birds.

Panorama of the middle of the north side of the Snaefellsness Penninsula at Grundarfjordur -- typical south-Icelandic scenery

Map of Westfjords, Iceland, showing stops and sights on Day 6 (2024 June 2) and Day 7 (2024 June 3, our last day in Iceland). On Day 6, we disembarked at a dock in Patreksfjordur and were driven for about an hour to a bird nesting cliff. On Day 7, we took a zodiac ashore at Thingeyri and then were driven for about 45 minutes south to Dynjandi Waterfall. This is on the south shore of the next fjord south of Thingeyri, reached via a roughly 8-km-long tunnel through the mountains. The multiple waterfalls of Dynjandi were powerful and beautiful. Afterward, we visited a museum that preserved some of the Viking way of life as it was ~ 1000 years ago.

Razorbill flying below the crest of Latrarbjarg Bird Cliffs on Day 6 = 2024 June 2. It was so windy that I did not climb to the highest point along the cliffs. So I never got close to nesting birds.

Razorbills on cliff (again, only poor pictures of birds in breeding plumage)

Common guillemots on Latrarbjarg Bird Cliffs. Can you spot the Brunnich's guillemot?

At Dynjandi Waterfall, with the top = biggest waterfall in the background and the bottom waterfall behind our heads.

The top and bottom of at least 6 major waterfalls at Dynjandi. It does not make sense to count more exactly, because the stream often splits into several vertically-overlapping waterfalls.

Scroll right to see this full panorama of the area around Dynjandi Waterfalls.

Uppermost of the Dynjandi Waterfalls -- 100 m = 330 feet high

Hridsvadsfoss

Gongumannafoss (Scroll right to see the full panorama.)

Selfie taken just before I turned around at the steepest part of the trail at Gongumannafoss

After the stop at the waterfall, we were taken to a nearby village with a "working museum" that partly recreates the Viking way of life from ~ 1000 years ago. We did not "dress up" ... but Mary did bake some Viking-era bread on an outdoor fire. And I tried to write my name in Viking runes (below).

"John Kormendy" transliterated into Viking runes. Not guaranteed to be correct!

We crossed the Arctic Circle within a few seconds of 9 PM on Day 7 = 2024 June 3. I am not sure how far north we got by ~ 12:30 AM, so I don't know whether the sun set briefly on that day or not. But starting around 2 AM on June 4th, we had no more sunsets until after our flight from Longyearbyen to Oslo late on June 24th.

June 3 PM to June 6 AM: At Sea, Cruising from Iceland to Jan Mayen Island

Throughout our time in Iceland, seas were almost calm and, while the wind occasionally got up to > 20 knots, it mostly was not a problem (except at Latrarbjarg Bird Cliffs on Day 6 = 2024 June 2). But during the evening briefing on June 3rd, we were warned that the ship was now starting to sail to Jan Mayen Island and that there were strong winds and stormy seas ahead. Sailing would get rough by about 4 AM on the 4th. That, of course, is exactly what happened.

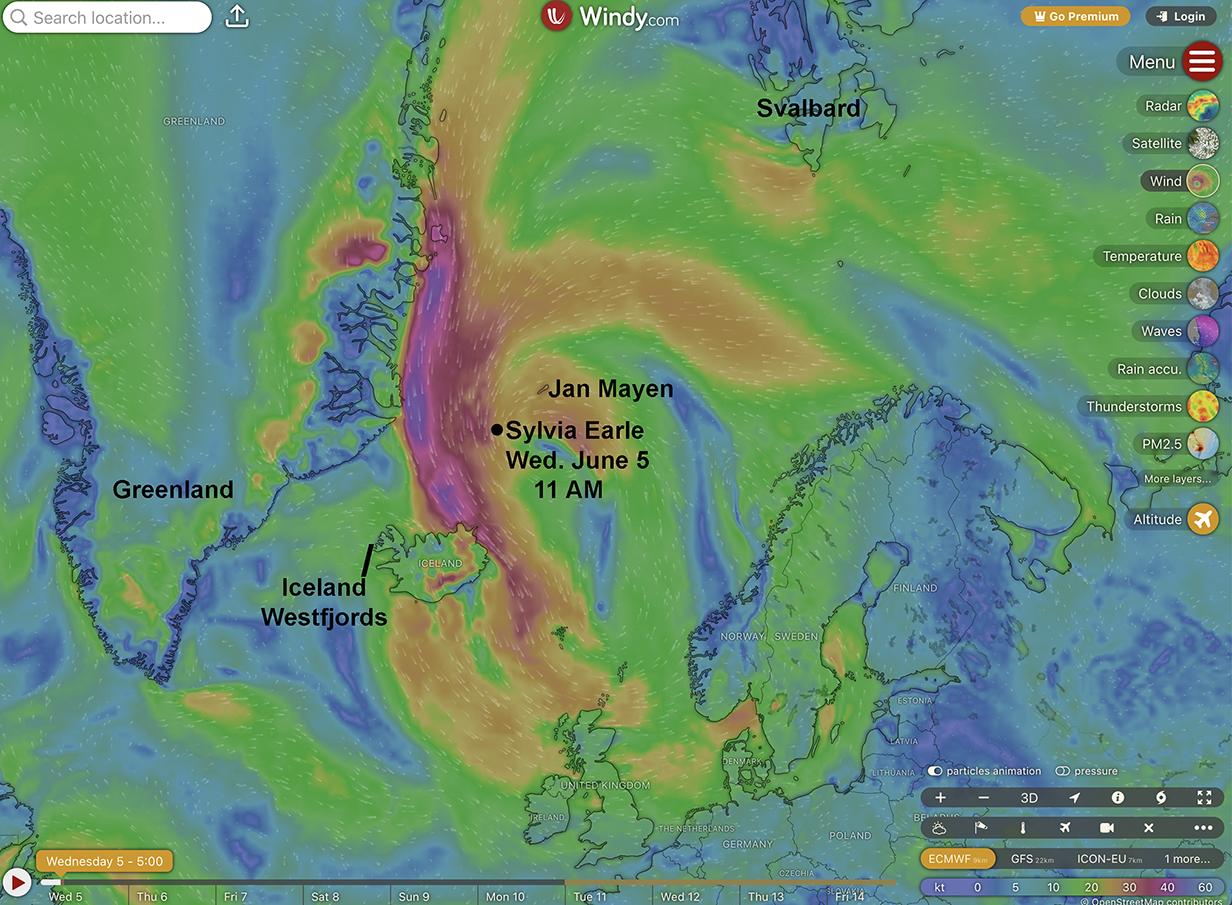

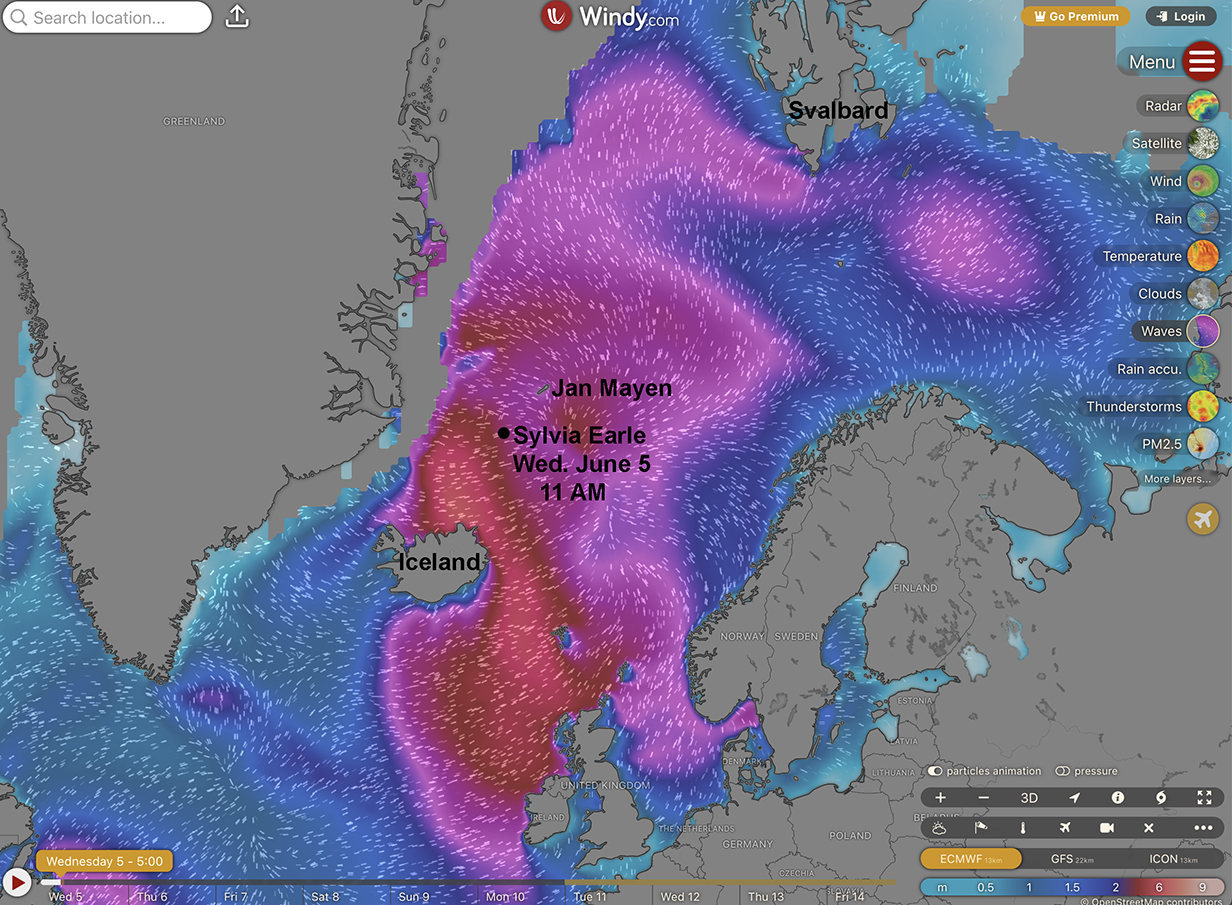

The expedition leader showed us expected wind and wave conditions overnight, using a quite wonderful web tool https://www.windy.com/?69.084,-2.505,4,m:fn4ahjh . The above picture shows the situation effective noon on Wednesday, June 5, as I write this. We are now more than half way from Iceland to Jan Mayen; the winds outside are still howling, and waves are high enough so that it is hard to walk, even with the ship's (very helpful) stabilizer "wings" deployed. Yesterday was worse, with steady winds of 50-60 knots and gusts up to about 75 knots. Waves were commonly 5-7 m from crest to trough. It was possible (using railings!) to walk the halls, but it was hard. Happily, we did not get seasick and even enjoyed dinner. Sleeping was bumpy but manageable. The irony is this: Iceland has very strict rules that people are supposed to use seat belts even in buses. Last night, I had the feeling that we could use seat belts attached to our beds. Stuff rolled around a little, with frequent loud crashes of glass in the dining hall. But we were OK in our suite.

Wave heights now, on day 2 of the Iceland to Jan Mayen passage, are a little less severe, but we are still inside the storm. The crew tried a trick yesterday, which was to sail directly north, close to Greenland, in the hope that ice floes would calm the waves. This worked for a while, as the above map (even on the next day) shows. Trouble is, there was too much ice. So we had to turn back south and then head NE, straight into the storm. It got pretty wild yesterday evening. I post pictures and videos, below. At noon on June 5th, conditions are getting marginally less enthusiastic.

This is how they prepare the hallway for rough weather. Ominous. So far, we have used the railings a lot, but we have not needed the bags. The storm is rather fun, actually ...

Adventurous weather, evening of June 4, 2024, at about 9 PM

The strongest wind gusts blasted the tops off of waves, filling the air with spray even up to our balcony.

Here is a movie of the storm taken at the time of the above pictures. The frame that introduces it, above, is at 19 seconds into the movie. My iphone had trouble maintaing focus, because our window on Deck 4 kept being by blasted by spray torn off the tops of waves by the wind. Still, we never felt in danger, and it proved possible to resist getting seasick by maintaining a feeling that we were having an adventure, not being threatened by any danger.

At 2:30 PM on Wednesday, June 5th, 2024, the wind has dropped a lot and waves have dropped mostly to 3-4 m. It is still hard to walk, but the worst is over. For now.

Scenery and Pelagic Birds: Cruise Along the West Side of Jan Mayen Island -- Evening of June 5th

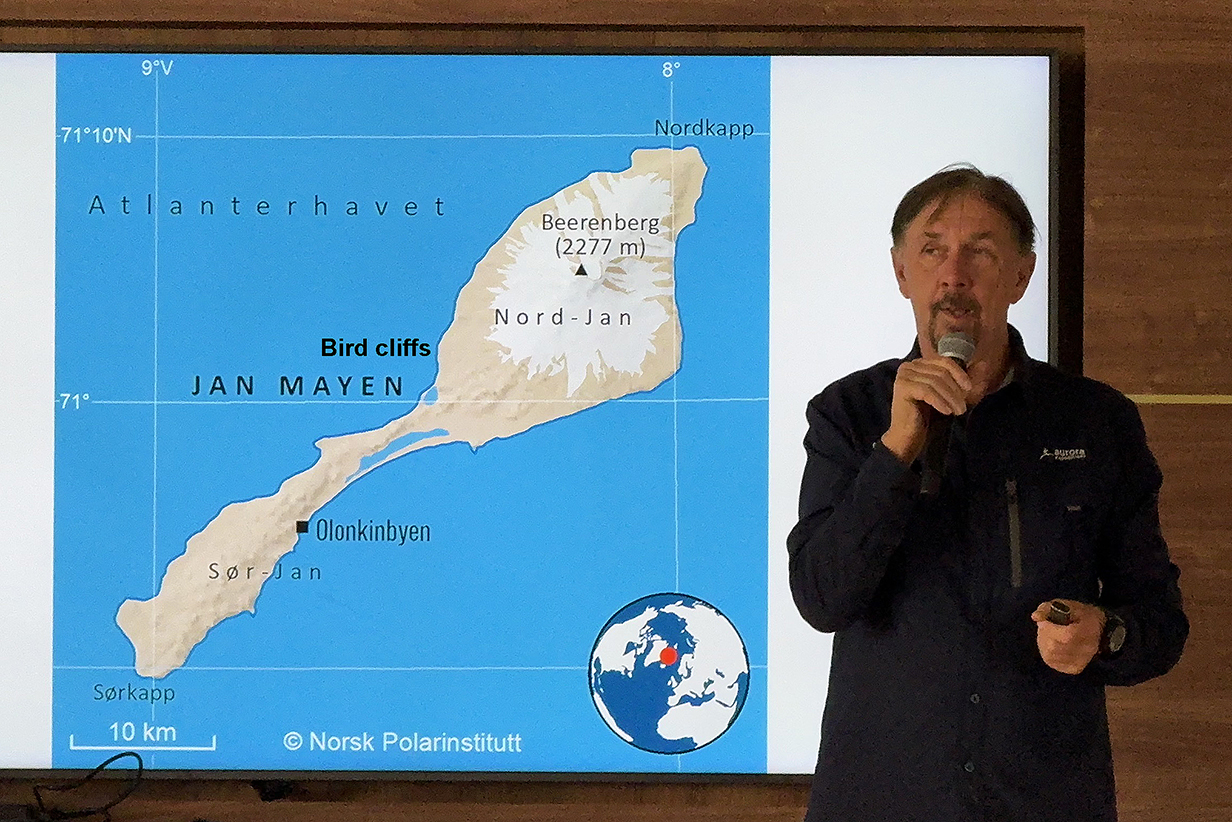

Lecture room aboard the Sylvia Earle during the June 4 evening briefing by Expedition Leader Howard Whelan. We expect to arrive at Jan Mayen Island tomorrow (Day 9 = June 5) at around 9 PM, after supper. On the way there, the weather remains slightly improved. It will be reasonably calm on the west side of the island, and then will get wild again on the 2-day passage from Jan Mayen to Svalbard. Pan right to see the full panorama.

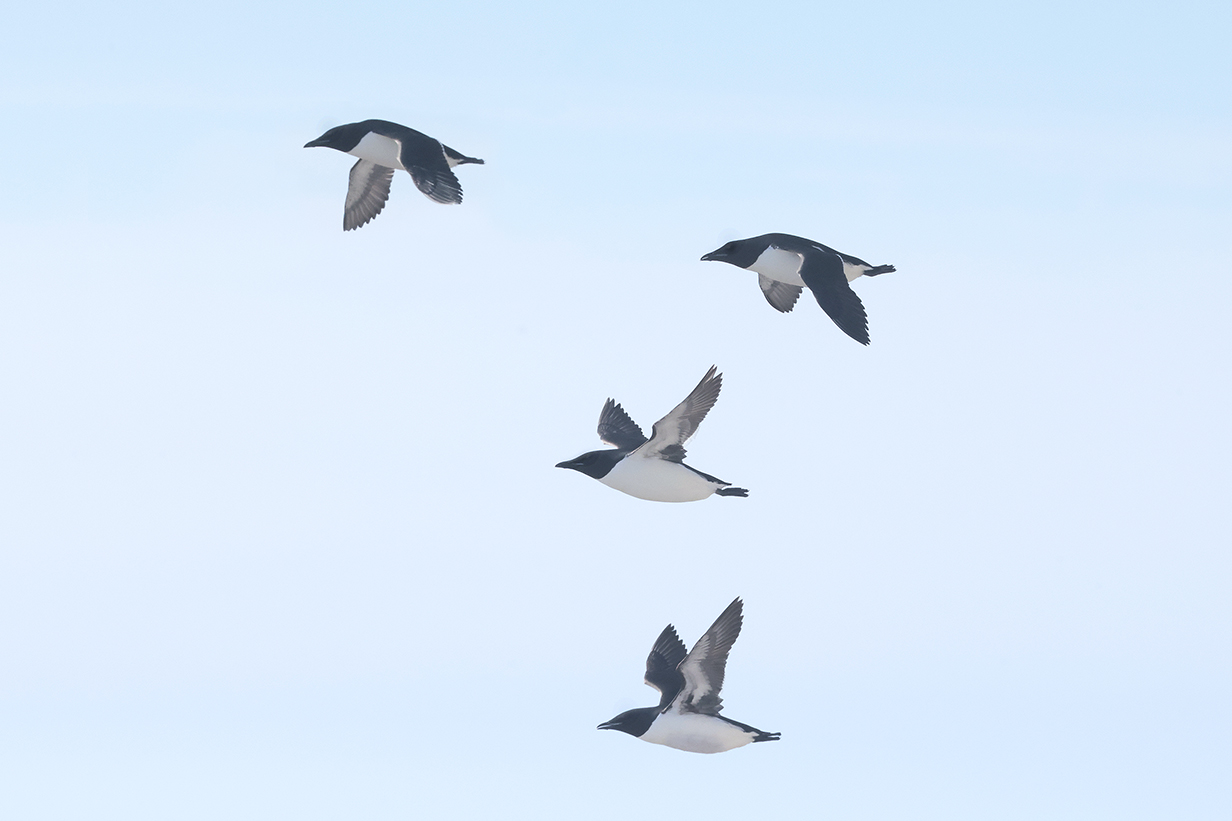

Map of Jan Mayen Island: We sailed along the left = west shore, mostly about 2 km out but slowing down very much and moving in closer to the bird nesting cliffs near the middle of the island. Pictures below show parts of the island from south to north. The island was used for whaling and whale processing (especially blubber into oil) for many years. The buildings associated with that are nearest the "N" of "Mayen". I did not photograph them. While we sailed along the southern, lower part of the island, many hundreds -- perhaps thousands -- of Northern fulmars sailed past us, flying faster then the ship. A few pictures of them are below. I also got my life bird Little auk, flying by, very tiny, very far away, and with very very fast wingbeats. At the end of the evening, at around 23:00 hr., we sailed by the volcano that dominates the northern half of the island, Beerenberg, 2277 m = 7470 feet high. Luckily, I was able to see and photograph its summit before we sailed into a fog bank and I went to bed.

Panorama of South Jan (scroll right to see it all)

Mountains on South Jan. This picture doesn't show it, but during this part of the passage, many hundreds of Northern fulmars, a few Little Auks, and an occasional other bird flew by.

Northern fulmar

Little auk (This is my life bird. The shape -- especially of the bill -- is right, and so, at least roughly, is the tiny size compared to the Northern fulmars. Of course, I can not guarantee that the auk and fulmars were the same distance away from me. But the auk was tiny and beat his wings constantly and VERY quickly. The coloration of the bird is correct, too, including the white trailing on the wings. I hope to get a closer view, but this is convincing enough to take this as my 4284th life bird and 3rd of the trip.

Four views of my life bird Little auk. The top-right view is the same as in the picture above. Little auks flew by fairly often, usually in groups of a few, but always far away. This was the closest bird that I saw.

Northern fulmar: I asked our bird specialist, Graham Snow, about what happened to this bird. He said that fulmars regurgitate a vile, oily, red mixture to discourage critters that threaten them. In fact, he and other crew members also saw this bird and understood that it was not in trouble. It clearly was strong and unharmed and perfectly able to fly.

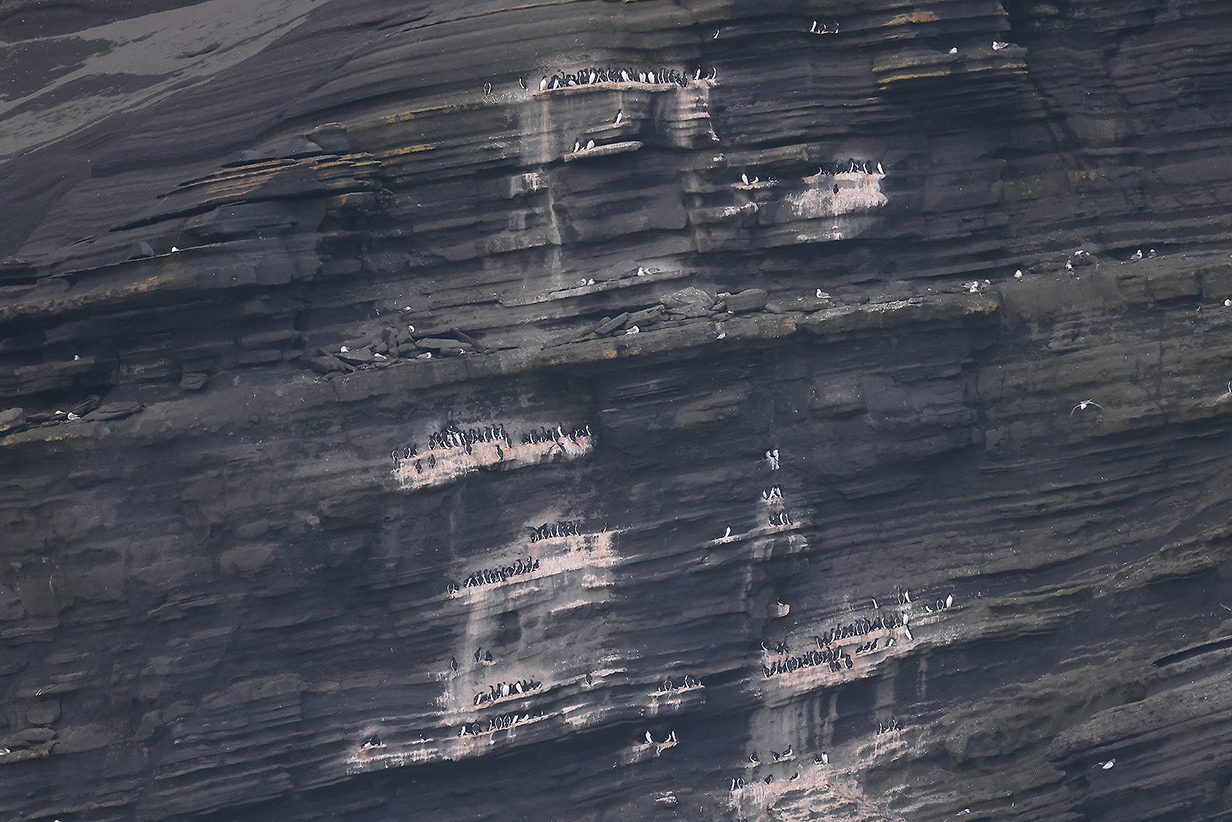

Sculpted rock and bird nesting cliffs on Jan Mayen Island (Scroll right to see the full panorama.)

Guillemots and Black-legged Kittiwakes nesting on the bird cliffs

This shows the seaward side of the cliffs in the above panorama

Closeup of the pillar in the previous picture. Fascinating rocks...

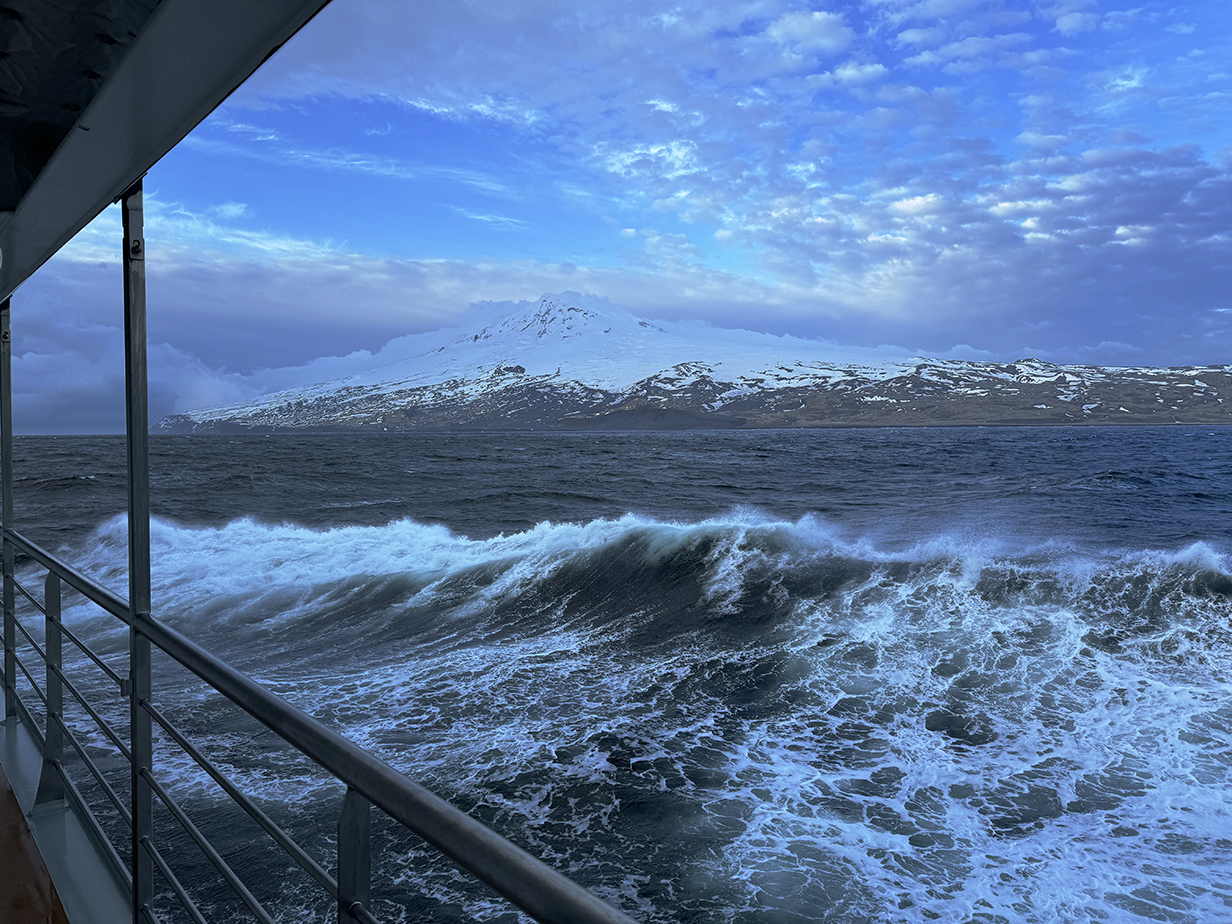

Approaching Beerenberg at about 11 PM (At this point, it was not yet clear whether I would see the summit or whether it would be clouded out.)

Happily, I got a clear view of the summit of Beerenberg. The sun was low in the north (at left, here, and behind clouds), so colors are very blue. It was a beautiful, serene view.

The summit of Beerenberg looks like it has a classic caldera. Pictures on the web confirm this.

During the night of June 5/6, we sailed on toward Svalbard. Seas got wilder again during the night, and by morning, it was once again hard to walk and eminently worthy of movies:

Stormy Seas and Pelagic Birds During Cruise from Jan Mayen to Svalbard on 2024 June 6 + 7

Here is a movie of stormy seas during the morning of 2024 June 6. Pelagic birds such as the Northern fulmars thrive in this weather. Note how the wind blows off the tops of waves. That effect was much stronger yesterday, when we had steady winds of 50-60 knots, with stronger gusts. Caution: This 3 min 50 sec movie file is 306 Mb in size.

June 8: Svalbard: AM Landing at Gnalodden; PM Zodiac Cruise at Samarinbreen

We arrived at Svalbard late in the evening of June 7. By the morning of June 8 = Day 12 of our trip, we were positioned in Hornsund, the southernmost fjord of Spitzbergen. The day was perfect: clear, sunny, and with only light winds. The temperature was about 28-30 degrees F. Mary and I both landed at Gnalodden, near the right-hand edge of the beach shown below.

Dramatic headland at Gnalodden -- wonderful view after the past few stormy days!

Birds -- mainly kittiwakes and some Brunniche's guillemots -- nested on the cliffs; there was a constant cloud of white gulls, especially around the top. I climbed about 1/2 way up the steep scree slope in the hope of photographing overflying Little auks but succeeded only in getting guillemots (below). We also visited one of the "satellite huts" of Wanny Wolsted, who is famous as the first woman hunter (mainly of polar bears) in Svalbard. And we very much enjoyed the spectacular scenery.

Gnalodden landing site in ankle-deep water roughly where the person is walking at right

Context panorama (scroll right to see it all) of Gnalodden landing site. Wanny's hut (see below) is at left with a group of 6 people. Mary is leftmost of the 5 people just left of middle, facing the hut and in gray-green waterproof pants for wet landings.

Satellite hut of Wanny Wolsted (1893 - 1959) at Gnalodden. She is credited as the first woman hunter in Spitsbergen. She was active in the early 1930s and spent 4 winters here and at her other huts. This tiny hut has three rooms, a main living room, a tiny bedroom, and an even tinier "mud room" at the entrance. It's a rough way to live, but she and others came here, we are told, to experience the freedom of Svalbard and to make what was then a good living. Impressive strength and endurance.

It has to be said: Most human history in the arctic is a history of exploiting nature, with rampant whaling, trapping, and -- in Svalbard -- coal mining. We are not enamored of this history, and it will not figure prominently in this web site. I concentrate mostly on nature -- the wonderful views and the birds. By and large, we skipped the historical sites; e. g., defunct whale processing stations.

Gnalodden scene

Perfect day: Sylvia Earle from half way up the scree slope below the cliff shown above

Brunnich's guillemots flew by frequently in small groups over the spot from which the above picture was taken.

Scenes from the afternoon zodiac cruise (also the Skua, below)

Sylvia Earle (Our cabin 429 has the double-width balcony directly above the "s" in "aurora expeditions". Being close to the water is a big advantage when pelagic birding. The main restaurant and our favorite table are directly above, with rectangular windows. The lecture room is also on deck 5, forward of the gap in windows.)

Arctic skua = Parasitic jaeger (Stercorarius parasiticus), in a not-very-good picture, standing on very bright snow

June 8 end-of-the-day panorama -- typical Svalbard mountain scenery

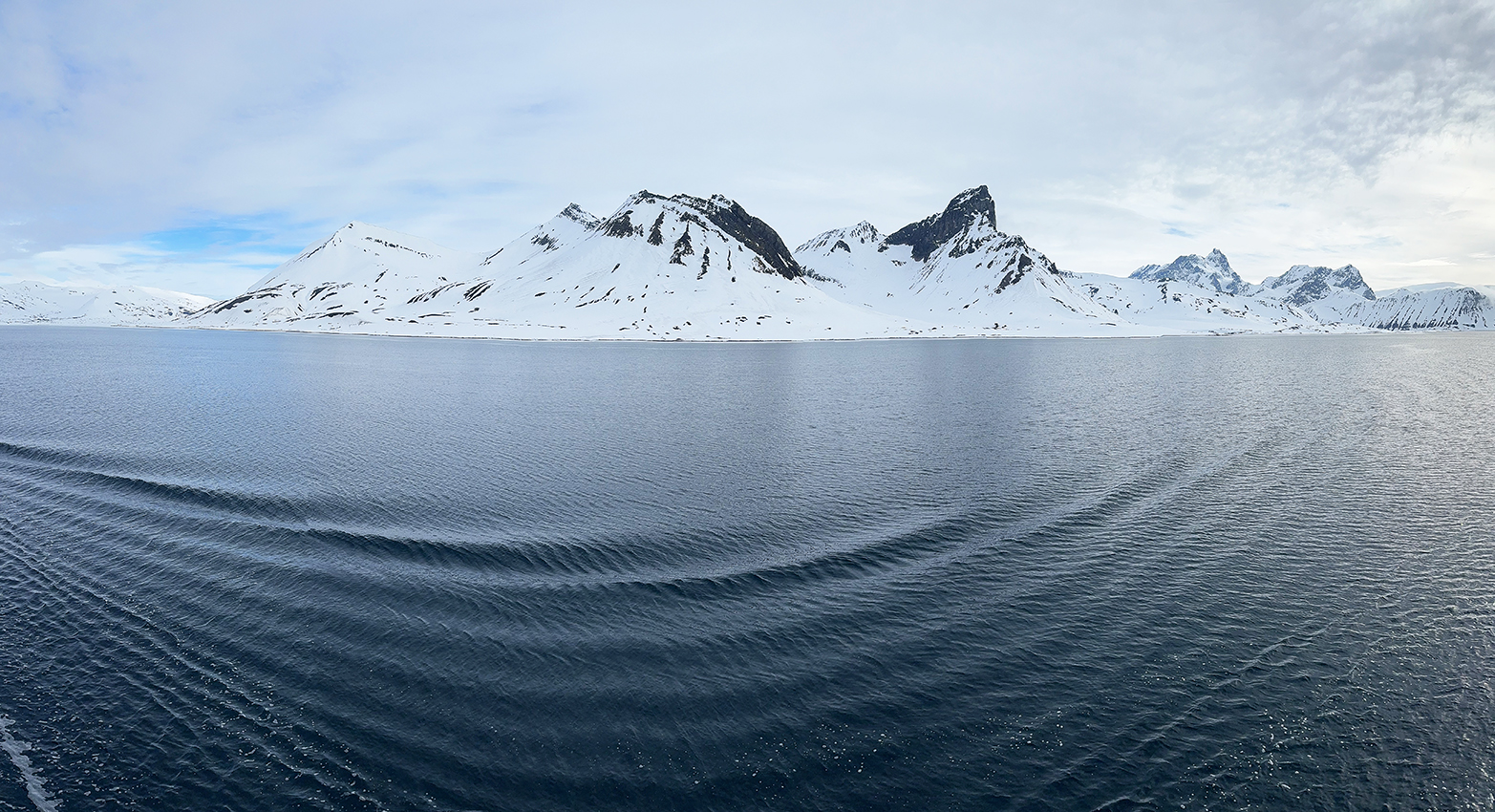

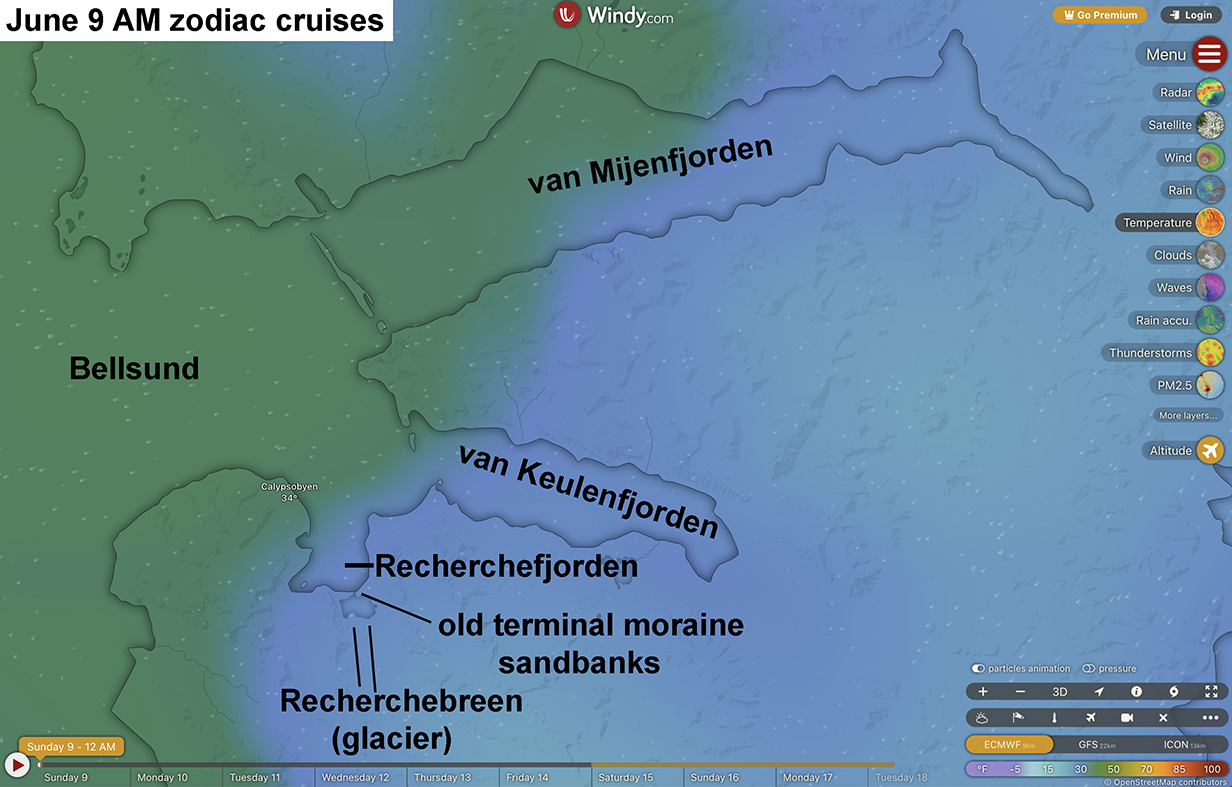

June 9: Svalbard: Two Zodiac Cruises at Recherche Fjord; Skipped PM Landing at Bamsebu

This morning, Mary rested while John took two zodiac cruises in Recherche Fjord, part of the next main fjord system north of yesterday's Hornsund. The first was part of the way up the fjord where the crew had seen walruses. The second was at the south end of the fjord, just outside (north of) the old terminal moraine sand banks shown above. The zodiacs were taken through the narrow opening south to almost the north end of the Recherche glacier, until we got stuck in thin "fast ice". We then sailed around this inner lagoon, looking at the glacier, at Black guillemots, and -- far away! -- at two reindeer. The head of the glacier is at N 77 deg 28 min 18 sec, E 14 deg 44 min 37 sec. The lagoon was calm but cold -- mid- to upper-20s F.

Waruses playing (A herd of half-a-dozen was more or less asleep on the beach -- not photogenic.)

Face of Recherche Glacier from our zodiac

Face of the Recherche Glacier, heavily cracked and crevassed. At its bottom is thin "fast ice", that is, ice that is fastened to the glacier and contiguous but, in this case, not thick enough to stand on. Our zodiac was run onto the ice until it stopped, several hundred feet, I would guess, from the glacier face. The moraine behind us (see the day's introductory map) shows that the glacier is retreating ... but not very quickly.

Seracs just behind the face of Recherche Glacier

Two humpbacked whales breached right in front of expedition photographer Jamie

At the end of the second zodiac cruise, the zodiac drivers found two reindeer very far away, sitting on the snow.

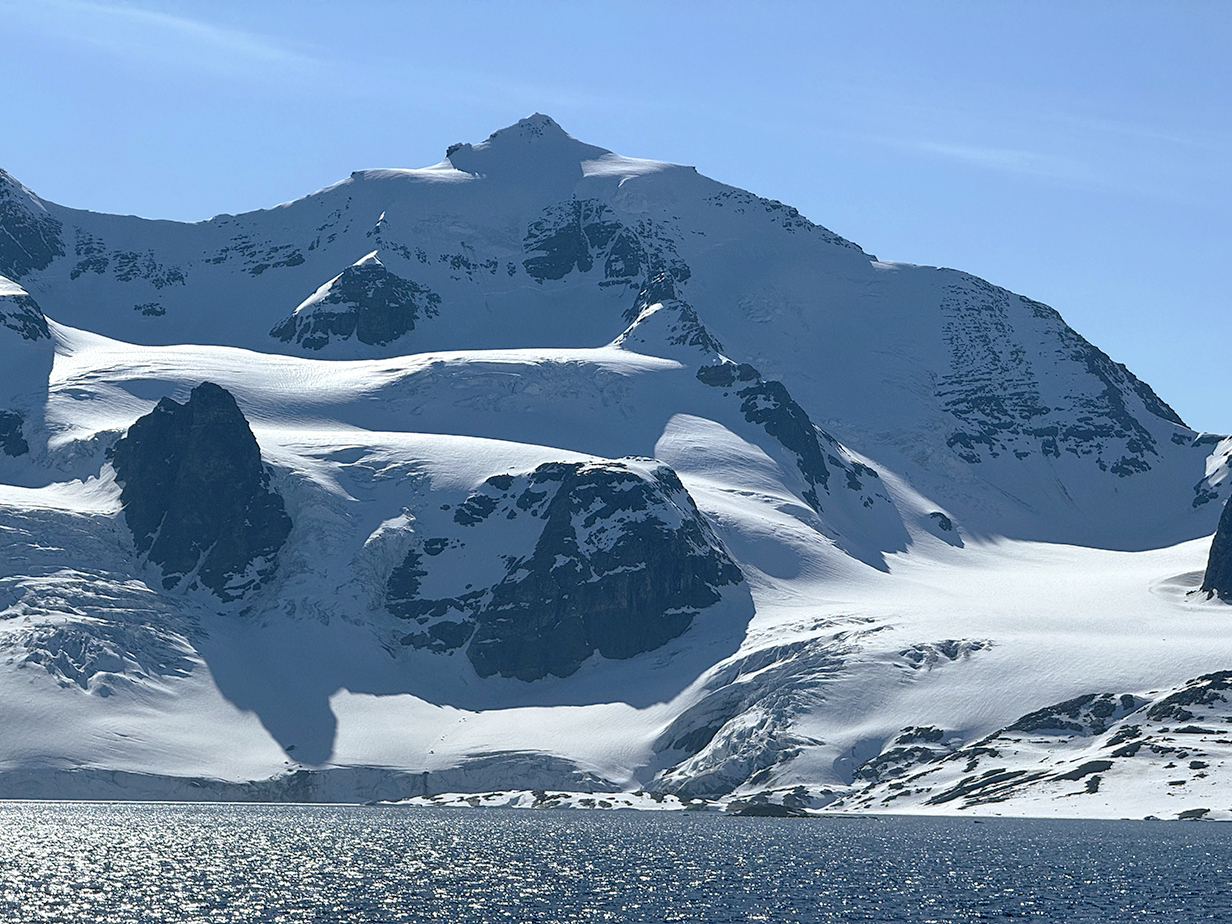

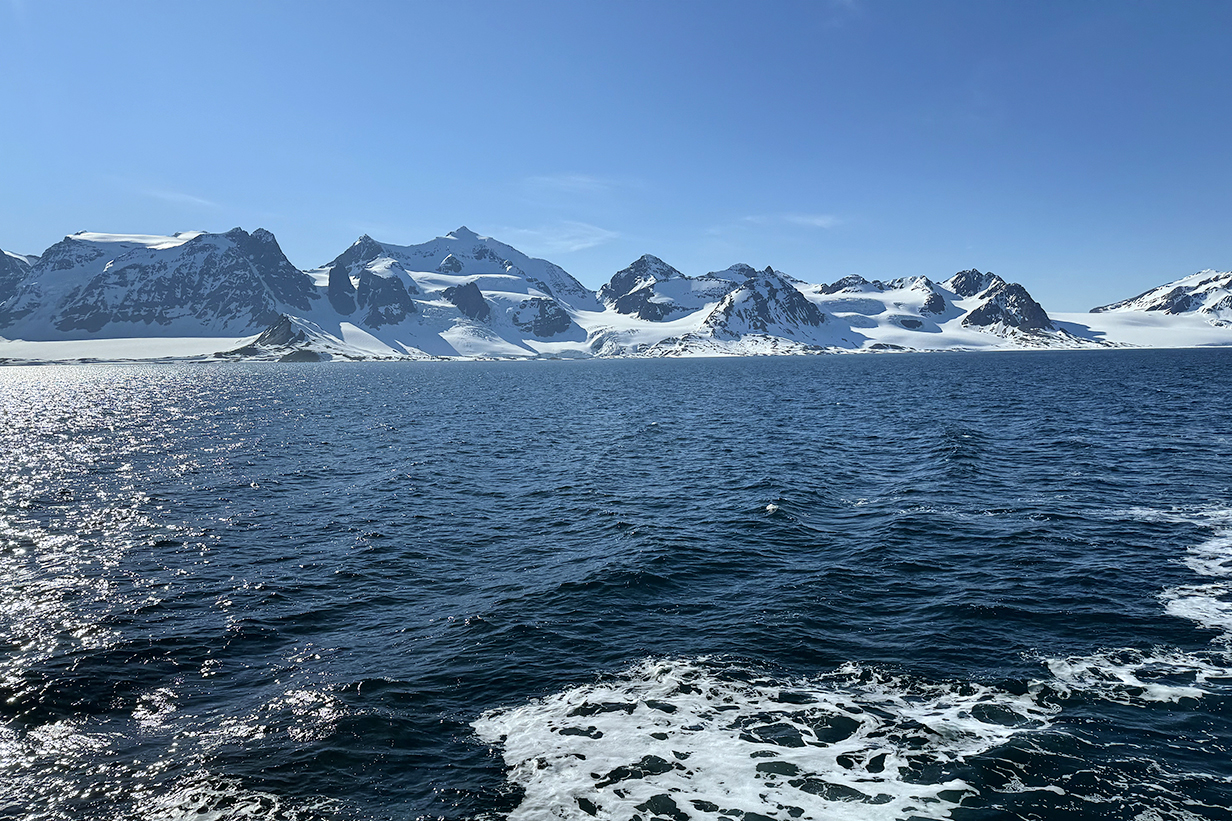

June 10: Svalbard: St. Jons Fjord; PM Cruising for Polar Bears

This turned out to be a day of gorgeous scenery from aboard ship. In the morning, there was a zodiac cruise of St. Jons Fjord, the small fjord just north of Isfjord, where Longyearbjen is located. John felt threatened by a cold after yesterday's long and frigid zodiac cruises, so we skipped the AM zodiacs, expecting a landing in the afternoon at a Alkhornet, which should be good for birds. In the event, the cruise planners changed their minds and spent all afternoon cruising, looking somewhat desperately for polar bears. This was the last chance for the present cruise, and most cruise guests are most interested in polar bears. Hints of sightings were transmitted to us -- people from other ships saw a bear on a carcass -- but our people did not find it despite very hard work. For Mary and me, this was therefore a restful day, with wonderful mountain scenery. And we get more chances to see polar bears in our second, "Svalbard In Depth" cruise, which starts tomorrow.

This is a 180-degree panorama of the wonderful scenery at St. Jonsfjorden on the morning of June 10. Scroll right to see it all.

Closeup of part of the above panorama

Sightseeing and some (largely unsuccessful) pelagic birding was mostly from our balcony of Suite 429, today.

In the afternoon, we sailed south between the island that makes up Forland National Park, just offshore from St. Jonsfjorden (see the Svalbard itinerary map, below) and the "mainland" of Spitzbergen. This panorama and the following pictures were taken along the east shore of the Forland island. The ship's crew were meanwhile scanning both coasts for polar bears.

Forland National Park

One more panorama of Forland National Park, looking back from a few miles farther south. These were the most aesthetically pleasing mountains of the first cruise.

Puffins (During dinner, at 7-7:30 PM, lots of birds flew by and/or hunted for fish. By the end of dinner, activity had almost stopped. This may, in summer, be a land of eternal sunshine, but the pace of life slows down drastically late in the evening.)

Northern fulmar, still waters, windless calm evening at around 9:30 PM, after dinner, after the trip slide show. This is the last picture of the first of our 2 Aurora cruises, from Iceland to Jan Mayen Island to Svalbard. Very peaceful and serene.

John and Mary Kormendy: Aurora Cruise "Svalbard in Depth" 2024

This cruise starts on June 11th with us remaining on board Sylvia Earle. It ends on June 24, when we disembark and are scheduled to fly from Longyearbyen to Oslo to Paris.

This map shows essentially all of our destinations in Svalbard, including the ones at the end of the Iceland-Svalbard cruise, above. Red filled dots locate destinations where John (or in the case of the Gnalodden landing, John and Mary) took part in a landing or a zodiac cruise. Red crosses identify destinations were we did not take part in landings or zodiac cruises. In some cases (notably St. Jonsfjorden), views from the ship captured spectacular scenery well. A few destinations where we did not take part are omitted to reduce clutter. Their dates are missing. The label for each destination includes the date in June when we were there. Some destinations (e. g., Longyearbyen) were visited twice.

The "north point" is not quite correct. What's marked is the official north point as recorded by the crew. We stopped there for much of a day. There was a "landing" on the pack ice. Pictures are included below, but John did not participate. Instead, I birded from our balcony and was rewarded with the only sighting by anybody on the trip of an Ivory gull, my "number 1" trip bird. The polar plunge also happened there. But the ship was pointed south during this time, and we sailed a little way forward before we stopped at the official north point. So I think we must have reached a few miles farther north than the coordinates indicated. That's also what the cabin TV indicated ... although the crew said that the cabin latitude and longitude displays were not accurate. "Bottom line" is this: We probably reached slightly farther north than the point indicated in the map, by a tiny amount that would not be visible at the scale of the map.

It is worth emphasizing how lucky we were to get to Andreeneset, Kvitoya. Most years, Kvitoya is cut off from cruise itineraries by pack ice and/or bad weather. And effective 2025 January 1, Norway will no longer allow cruise ships to go there. So this really was a "once in a lifetime" experience that we treasure.

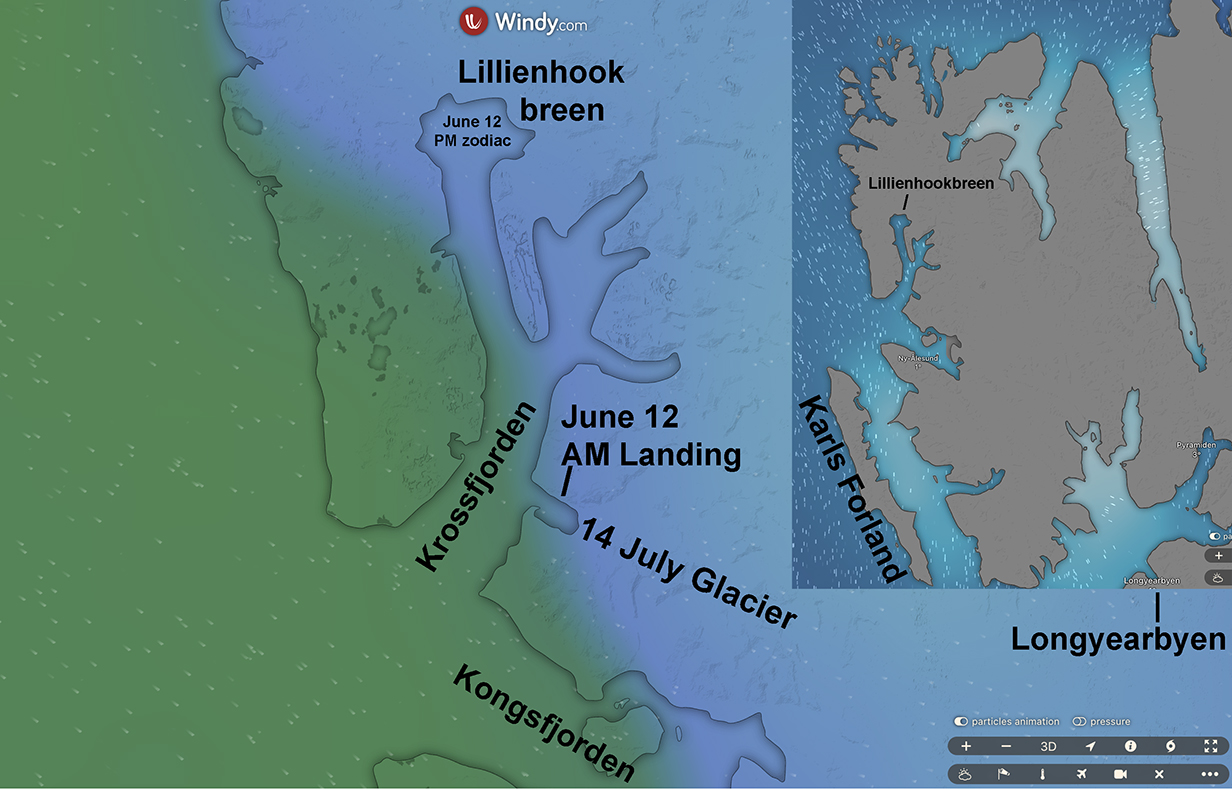

June 12: Svalbard: AM: Landing Near 14th July Glacier and Zodiac Cruise

PM: Zodiac Cruise at Lilliehookbreen

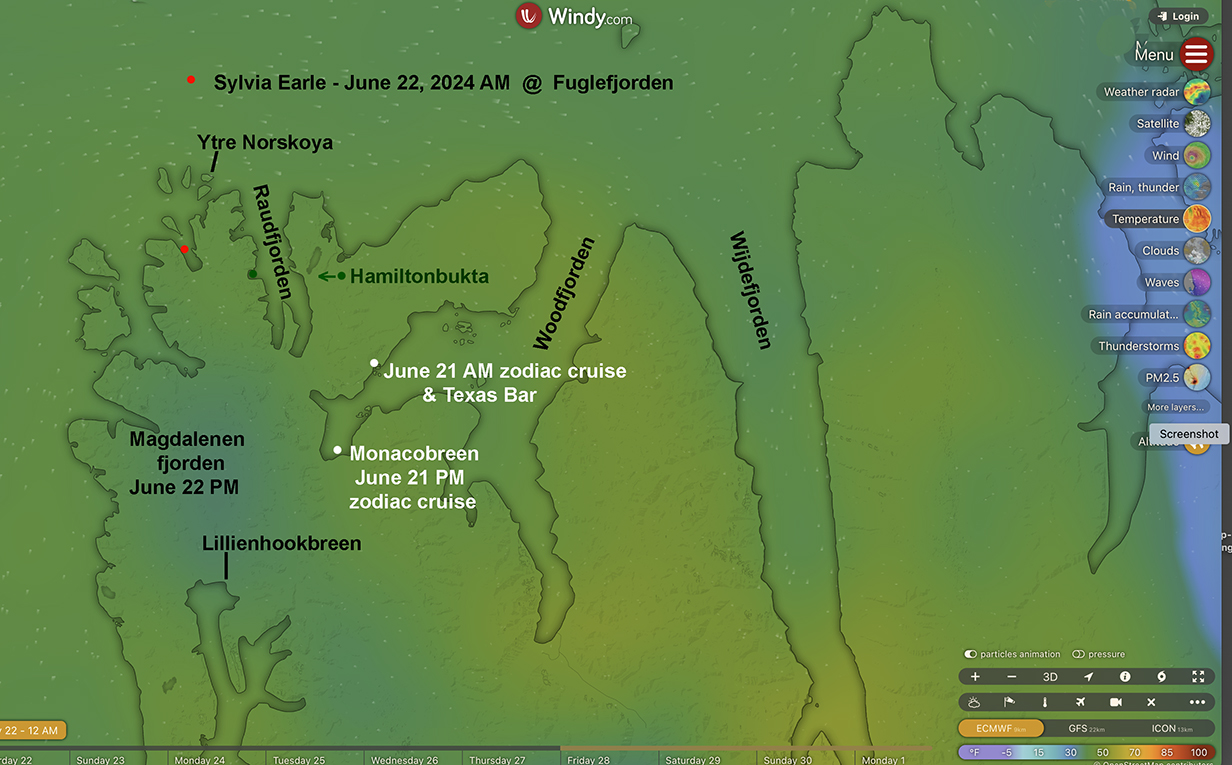

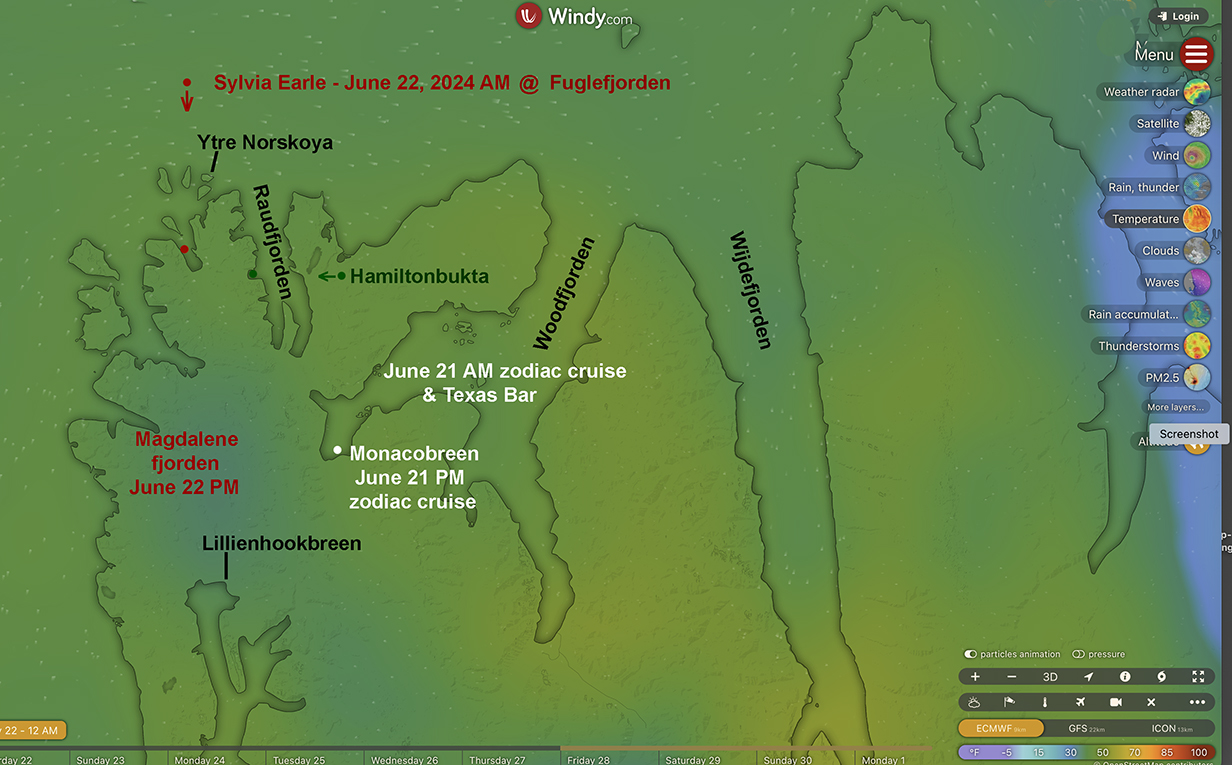

Windy.com maps of NW Spitsbergen showing the location of today's AM landing and PM zodiac ride

This morning's landing had some of the lushest vegetation in Svalbard -- mosses, lichens, and a few flowers. It is "fed" by runoff from the bird cliffs above and helped by southward-facing slopes. This above idyllic scene was the most beautiful spot. I immediately suspected tht it would be prime habitat for Snow bunting. Almost immediately, I was a flash of white wings. And within a few minutes, I had my life bird male Snow bunting. Beautiful and satisfying!

In the background is the 14th July glacier, named after an important French holiday.

Snow bunting (This male is my life bird.)

Flowers, lichen, rocks -- a marvellous, miniature world, thriving in a harsh land

Barnacle geese seen during the zodiac cruise that followed the above landing

Barnacle goose

Barnacle geese thrive in rough habitats, presumably because they are safe from predators such as arctic foxes.

Same is true for Brunnich's guillemots: The ideal nesting place is a bare ledge on a vertical cliff, nicely overhung, reachable only by flying.

Atlantic puffins and a Brunnich's guillemot

Atlantic puffins

The summary of where we have been that was posted on the ship listed, for this morning, besides the birds that I illustrate here, "billion-year-old rocks!!". These must be them. We saw wonderfully tortured rocks many times during this trip.

Black guillemot (We saw them often, especially during zodiac cruises. They were not shy, but lighting was usually so bad that they looked completely black and white. This time, the lighting was good enough to show detail.)

The morning's zodiac ride finished with a closeup look at the 14 July glacier. As glaciers lurch forward, complicated fracturing histories produce an endless array of abstract art.

This is an 180-degree panorama of Lilliehookbreen from the balcony of our suite, taken before the June 12th afternoon zodiac cruise around the face of the glacier. Scroll right to see the whole panorama.

Lilliehookbreen in more detail, still from our balcony ...

... and as we got closer on our zodiac

Some seracs looked ready to break off and fall at any moment.

The feeling of sailing below these ice cliffs -- more than 100 feet high -- is a remarkable mixture of the inexorable power of the glacier and yet the potential fragility of seracs that, one realizes, could collapse into the water at any moment. This is unforgettably impressive.

And nature's artistry: In places, the face of the glacier reminds me of August Rodin's Gates of Hell ... but with no tragic connotations.

Arctic terns resting on an iceberg

Layered ice blocks on the face of Lilliehookbreen -- distant and close view

The large amounts of ice near the face of the glacier show that it is calving a lot. This picture also gives a sense of scale: even small icebergs dwarf our zodiacs.

Gradually the weather turned colder and windier and even the birds started to tuck their heads. That's when our afternoon zodiac cruise was ended.

June 13: Svalbard: AM: Photography Zodiac Excursion at Hamiltonbukta; PM: Off

Windy.com map of the north-west part of Svalbard, directly north of where we have been on previous days. John took a long morning zodiac ride around Hamiltonbukta, which I think I have correctly identified. It went past a succession of steep cliffs and "pointy mountains" (read "Spitsbergen") separated by small glaciers. Views were generally beautiful. After this long and cold outing, I skipped the PM excursion to the opposite shore of Raudfjorden.

This morning, John took a "photography zodiac ride" ... which was rather a mistake. The first stop was the bird cliffs shown here, but we are never allowed to get close enough to get good pictures. Also, on zodiac rides, you can be lucky (as I was yesterday) and get to sit on the side from which you see almost everything, or you can be unlucky (as I was today) and get stuck on the side from which you see almost nothing, if, like me, you can't twist or kneel down and look up. They always advertise that they'll turn zodiacs so that everybody gets good looks. But that almost never happens. Moreover, at > 2 hours in 0-degree-C weather, often driving fast, zodiac rides are too long and too cold for me. Still, the scenery was almost always spectacular. And I got a few pictures.

Hamiltonbukta mountains and glaciers

Black-legged kittiwakes during the zodiac cruise

Near the end of the zodiac cruise, people on our partner zodiac spotted a reindeer far up the adjacent mountain slope.

A last look at Hamiltonbukta ...

In the afternoon, we anchored across Raudfjord from Hamiltonbukta and most people did a shore landing and hike. I did not, being still cold and tired from the morning. But the views from here were glorious, and a panorama of them is shown below. This shows how the location of the ship is displayed on each suite's TV.

Panorama looking west across Raudfjord from near Hamiltonbukta

John's 76th-birthday dinner aboard Sylvia Earle. The background shows 1/2-billion-year-old, heavily eroded Devonian-age sandstone mountains that are much different from the more rugged, "pointy" mountains west of the fjord that motivated the name "Spitsbergen". These are among the mountains the we have seen for the past few days and in John's zodiac ride this morning. The tiny polar bear on the table is a present from the ship's Hotel Manager, Mr. Singh, who has been extraordinarily gracious and helpful to us during both cruises. So far, it is the only polar bear that we have seen.

Which, arguably, is good. Any bear that's here would be stressed from lack of food. There are almost no seals and few walruses here. No pack ice. We plan to sail north to find pack ice and hopefully polar bears (and, I hope, Ivory gull) starting tomorrow.

June 14: Svalbard: AM: Landing at Ytre Norskoya Island; PM: Ship Cruising to & at Moffen Is.

Windy.com map of north-west Svalbard. John made the morning landing and stayed near the landing site shown below and (dressed too much like the Michelin Man) managed to stumble up the penninsula behind him until he got a view west. In the evening, after supper, we reached Moffen Island, a tiny and almost-flat sand bank outside the above picture to the upper-right. There were a few walruses there, too far for effective pictures.

Ytre Norskoya panorama taken just inland of our landing site. The ship is anchored 1 km offshore. A few people on the "long hike" are visible on the skyline above the three people farthest left in this picture. Above the head of the red-jacketed, nearest crew member near the center: the low hills in the distance are part of the Devonian, highly eroded landscape. The taller mountains immediately to their right and slightly closer -- like the rocks undergfoot here -- are part of the metamorphic rocks that form the "Spitsbergen". Between them and toward the right is the fjord that includes Hamiltonbulta, where we went yesterday. This pano is centered looking roughly east. Behind me is a small rise, and from the top of it, I show below another panorama looking west. The Great skua also shown below was at the western tip of the hill at far right in this picture, well outside this frame and not seen until about 1/2 hour after this photo was taken. As always, scroll right to see the complete panorama.

Panorama looking westward from the high point behind where the above picture was taken. Scroll right to see it all.

Barnacle geese

Great skua atop the cliff just south of our landing spot on Ytre Norskoya (This is my life bird.)

I was lucky -- an expedition staff member climbed up toward the skua, maybe to take pictures. Sure enough, the skua first put on a threat display ...

... and then flew away. For once, I was prepared!

This picture and the next 3 show our suite 429 on deck 4, close to the water to favor pelagic birding. It is a "handicapped cabin", which is also convenient because it is big, because the bathroom (behind Mary) particularly is big, and because the extensive hallway to the right of Mary has handrails that are perfect for hanging clothes that we need to dry. Our cabin is also convenient because it is very close to (only 2 suites separated from) the "mud room", where we get dressed for and board zodiacs.

Here, John is in the corner of the cabin from which he took the above picture. He is still "Michelin Man" dressed for the landing at Ytre Norskoya, in 7 layers below the waist and 6 layers above the waist, not counting the cap .

John has a convenient office where he can keep documentation and where he can, with his laptop, keep the trip web site more-or-less up to date ... enough, at least, so that we can remember the locations and order of pictures taken. We had the same cabin number and layout on our Aurora/VENT cruise to Antarctica in November-December of 2022.

A panorama gives the best impression of the "feel" of our cabin.

Later in the afternoon, on our way to Moffen, we took a detour south into the northern part of Woodfjorden to a place called Slakstranda, at 79 degrees 42.4 minutes N latitude and 14 degrees 15.8 minutes east longitude. It is marked in the Svalbard intinerary map. Here came the announcement that most passengers ardently awaited -- our first polar bears.

This is mama bear, resting after a good feeding. She was our first polar bear of the trip, well seen (although far away) by both Mary and John.

Turns out that she was travelling with 2 almost fully grown cubs. The bear specialists among the crew estimate that they are ~ 2.5 years old, unusually full grown to still be travelling with their mother. All three bears are conspicuously well fed -- there were several mostly-eaten carcasses of (possibly) dolphins on the beach below. The trio was probably at least 1 km away, but it was clear that the cubs were in high spirits and playing. It was an unusualy privilege to see them together and so far south.

Tonight, we were delighted to have dinner with the ship's Hotel Director, Mr. Balvant Singh. He has been extraordinarily gracious and helpful in solving a few subtle but troublesome problems for us. Interesting to get glimpses into a successful life that got its start in Agra, where Mr. Singh and friends used to play cricket in the gardens of the Taj Mahal!

We passed 80 degrees north latitude within a few seconds of 9:00:00 PM, on our way north to Moffen. Recall, coincidentally, that we passed the Arctic circle within a few seconds of 9:00:00 PM on Day 7 = 2024 June 3.

We passed Moffen late in the evening. The crew were hoping for walrus but were disappointed. We don't remember seeing Moffen, so I think we had gone to bed.

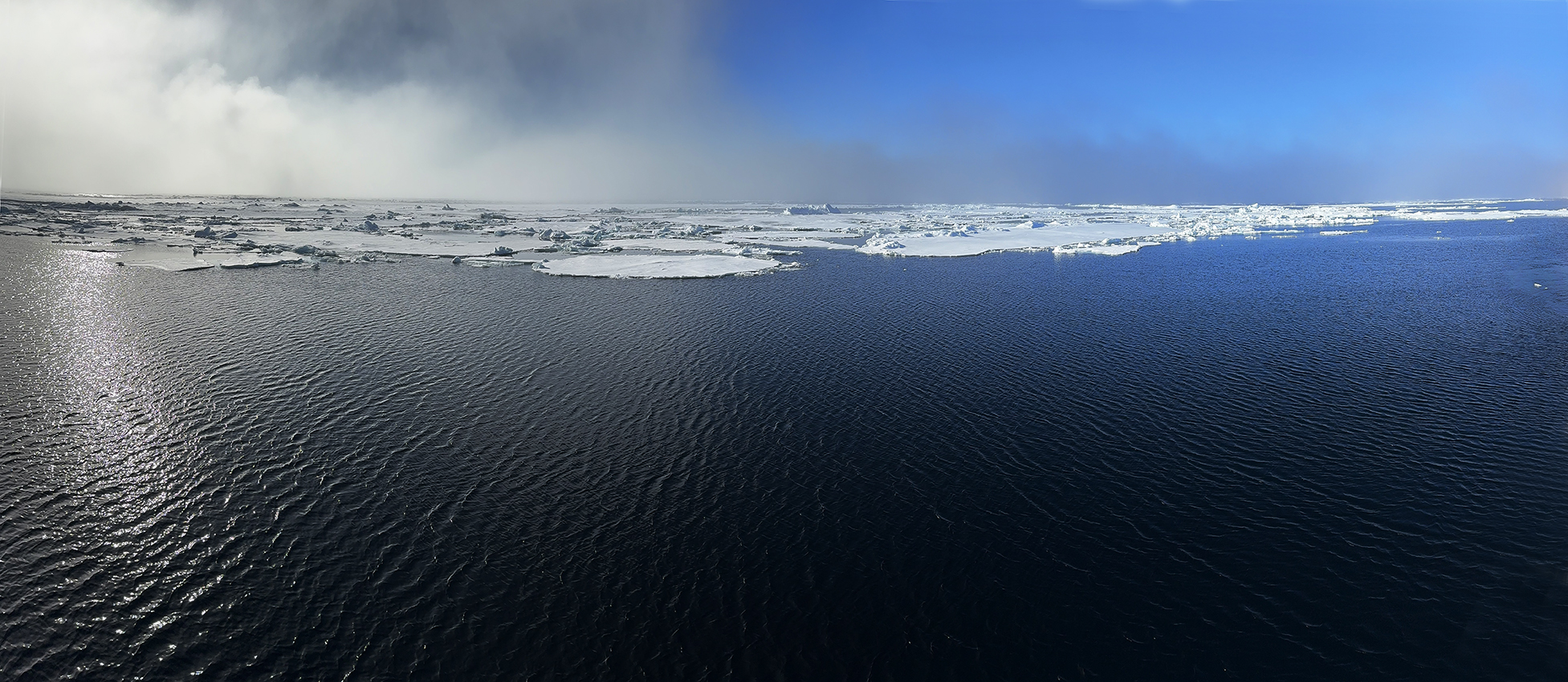

June 15: North of Svalbard: Cruising the Pack Ice

This morning, we were scheduled to make a landing at Phippsoya ... but thick clouds were too low. In polar bear country, this means that we can't risk going ashore, because the crew can't see whether there are bears waiting in the clouds for a meal to come ashore. So -- as so often happens in the (ant)arctic -- Expedition Leader Howard Whelan and crew changed our plans in real time and decided that we would sail north immediately and see how far we could get before we were stopped by ice. This was a happy decision for Mary and me: we prefer to be in drift ice as much as possible. We love the "mobile art" of wonderfully varied ice floes and the way they swirl and collide, always gently, and make continually varying artistic compositions. Moreover, we love the absolute stillness and peacefulness. We have missed this, since our two trips to Antarctica.

First, though, along the way:

Small herd of Atlantic walrus

Very rarely, we saw small groups of walruses on ice floes.

Black-legged kittiwakes were with us most of the time.

Ice creates an endless pageant of mobile art.

Later today, we sailed slowly north to just above 81 degrees N latitude. Wonderful ice floes, drift ice, and pack ice all day. I have missed the absolute silence and peacefulness of the high latitudes, south in Antarctica and just to the north of Svalbard, here.

This movie gives a feeling for the immense peace that we feel, sailing through scattered ice floes on a perfect, calm day. It was one of the greatest pleasures during both of our Antarctica cruises and during the present, Svalbard cruise, as we sailed north of the islands toward the polar pack ice.

Ivory gull (This is my life bird!)

Ivory gull (Same bird -- all white except that the inner 2/3 of the bill is gray and the tip is yellow. This rare and hard-to-see bird has to be my "number 1" trip bird.)

The Ivory gull made one more pass by the ship, farther away and flying back north. I never saw it again. According to the ship's records, nobody else saw it at all.

Small ice floe

Bearded seal -- one of the few seals that we saw during the trip, later in the afternoon of June 15th.

"Fogbow" -- sunlight refracted in fog

I can't resist posting another movie of what it feels like to sail with an fogbow.

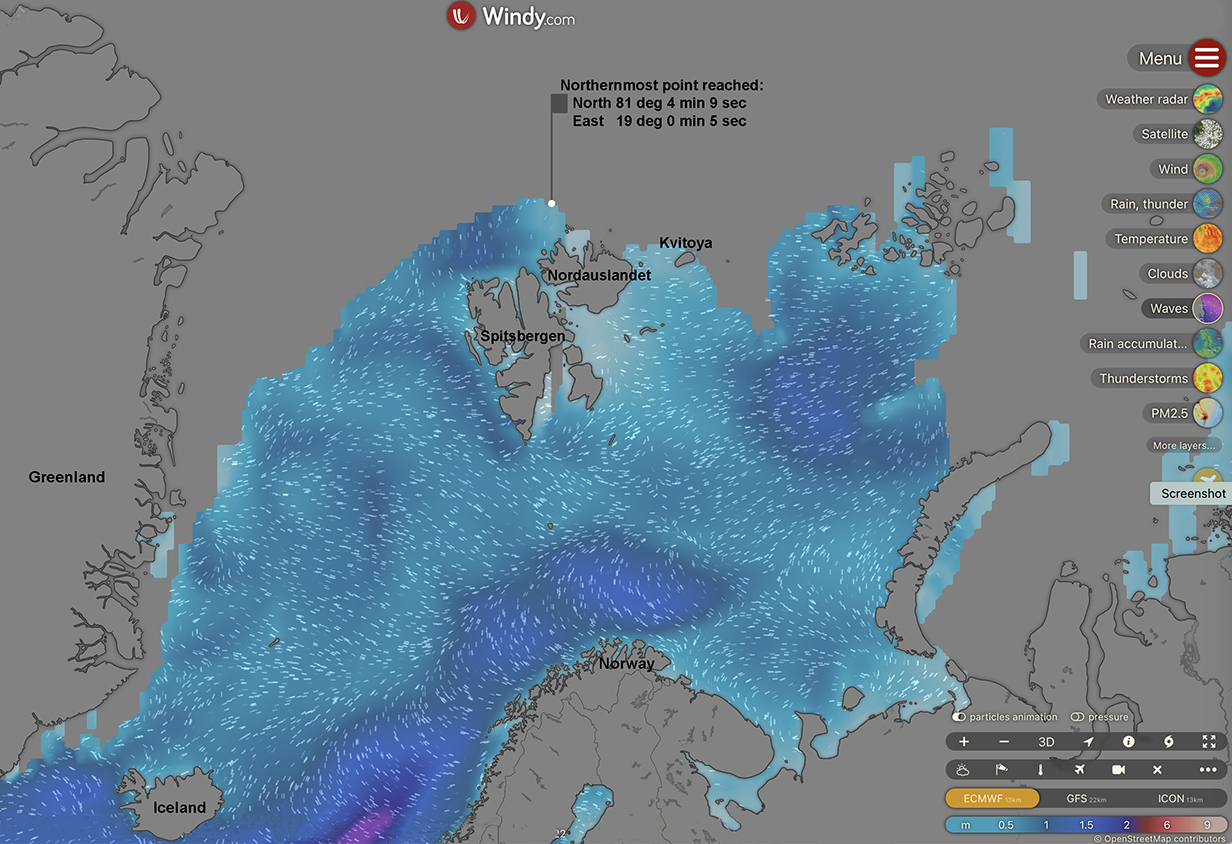

Some time this evening (not exactly noted by announcement), we reached our northernmost point of the voyage. There was some disagreement between what was posted on the TV ship's location map (the farthest north that I saw it mention was 81 deg 4 min 52.7 sec) and the value that I was told was correct (in the above map). Anyway, we were within about 620 +- 20 miles of the north pole. The contiguous north polar ice cap was not far north of our north point.

This is a photo of Earth from the north taken mid-July 2024 (from Getty Images). The previous map shows that we reached very close to the contiguous north polar ice cap as of June 15th.

June 15, 2024 end-of-the-day panorama, just before supper -- absolute stillness and serenity

June 16 AM: Cruising the Pack Ice; PM: Sailing South Through Hinlopenstretet to Nordauslandet

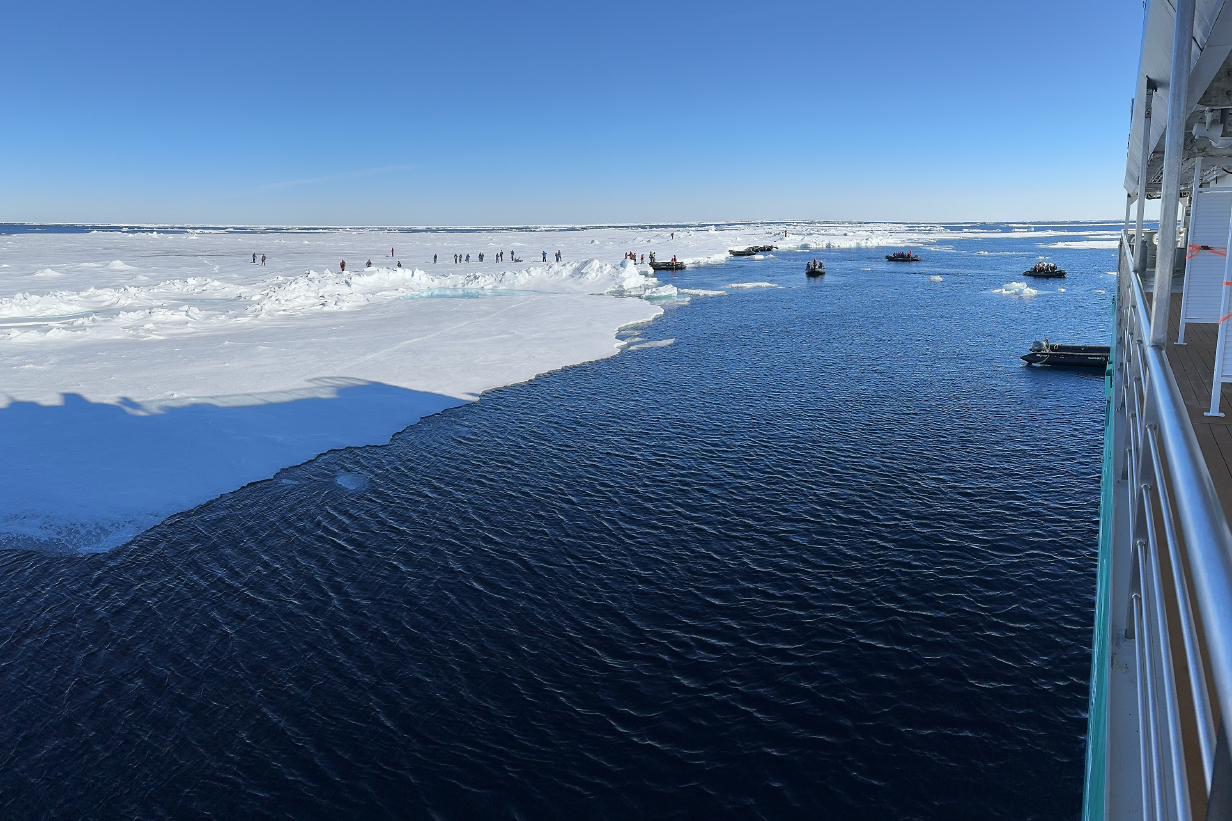

We stayed overnight at (more or less) our northernmost point. On June 16th, most people on the ship made a landing on the beginnings of the pack ice. And a few people took the traditional "polar plunge", rewarded with much raucous applause and, later, a certificate. I stayed on our balcony, luckily positioned where I could get pictures of the ice landing. My aim was again to look for Ivory gull. None showed up.

Landing on the north polar pack ice

After the landing, there was a zodiac cruise: Scroll right to see the full panorama.

At our north point, we approached the transition from major patches of connected sea ice to the contiguous (but, in Spring, shrinking) north polar ice cap.

The "polar plunge" took place the same evening. After that, we sailed south overnight through Hinlopenstretet to arrive at the SE corner of the glacial ice cap of Nordauslandet, which flows into the see there as Brasvalbreen.

June 17 AM: Zodiac Cruise at Brasvalbreen; PM: Sail to Kvitoya Island

Windy.com map that shows the site of John's AM zodiac cruise around the sea cliffs of the Nordauslandet ice cap and then slightly NW to the eroded sedimentary-rock desert on which we saw walrus and a polar bear.

AM panorama of the south ice wall of the Nordauslandet ice cap, the 3rd-biggest ice cap in the world after the ones in Antarctica and Greenland. Very impressive to sail east (right in this picture) all afternoon along that seawall ... whose top then rises gently into the distance in a giant dome that covers the eastern, main part of Nordauslandet. That dome is evident in this panorama taken from deck 8.

With such a clean icewall to the glacier cap of Nordauslandet, you tend to get cleanly calved, big icebergs. Special melt processes produced a variety of uniquely different icebergs that were, for me, the highlight of this zodiac cruise.

Fantastic icebergs: I should emphasize that I have only adjusted brightness and contrast to overcome the visual impression of being drowned in brightness. In fact, I made the color balance marginally redder, in case my iphone overemphasizes blue. I have not increased the color saturation. Glacier ice can be wonderfully artistic.

This was the most fantastic iceberg that we saw. Here, I have adjusted only brightness and contrast: no color balance or color saturation was changed.

Same iceberg from a slightly different angle. Again, only brightness and contrast have been adjusted.

Same iceberg from a slightly different angle. The iphone camera adjusted the color balance slightly with this different sun angle. Both versions -- this one and the one above it -- look gorgeous.

I can't resist adding this picture. It recalls that we are on a zodiac cruise, and -- even though both zodiacs are at different distances than the iceberg -- they do give some sense of scale. The iceberg is BIG. Also ... I don't usually indulge in fantasies about icebergs or clouds looking like people or animals ... but it is hard not to notice that this iceberg from this angle looks a little like a hungry lion contemplating a meal.

One more view of the above iceberg, upsun, from in front of the "mouth".

Scalloped iceberg (This is apparently a common phenomenon, especially well illustrated here. Why? This is far from obvious. I googled the question and got this answer: "Previous work has suggested that scallops form due to a self-reinforcing interaction between an evolving ice-surface geometry, an adjacent turbulent flow field, and the resulting differential melt rates that occur along the interface." This is spherically obscure. It is a quote from the abstract of this article ... which is also spherically obscure to me. Interesting that such an obvious, clearcut, and -- frankly -- beautiful phenomenon is so hard to understand.)

But fascinating and easy to enjoy.

One more big iceberg and the glacier than spawned it ... together with a Great black-backed gull

Polar bear ... very interested in several groups of walrus, all around the shore. This is the only excursion on this trip during which I did not take my Canon camera and 100-500 mm zoom lens. Sure enough, we got our best look so far at polar bear, albeit still from far away so that we would not affect its behavior or put it or ourselves in danger. As a result, I have only this conspicuously poor iphone picture of what was an unusually good sighting. We watched the bear for a long time, hunting (though not very seriously), playing, and "flaking out" as flat as possible on the ice to stay cool on what, for the bear, was probably a warm morning. Temperatures were within a degree or two of freezing.

As the bear wandered closer to the walruses, they took no chances and slipped quietly into the water. In the background is the old, eroded part of Svalbard, which dominates its eastern side. Note also the grounded iceberg (with the Great black-backed gull, above). Ornate icebergs were, for me, the most unique aspect of this zodiac cruise.

Walruses

South ice wall of Brasvalbreen again, this time from closer. As nearly as I can tell, it is mostly around 100 +- 20 feet high. We sailed east and then NE along the sea wall for most of the early afternoon of June 17th. By supper time, we were in more open water ... although with ice visible in the distance in all directions, on the way to Kvitoya Island, tomorrow morning.

The glacier cap of Nordauslandet and this sea wall are exceedingly impressive. Scroll right to see all of this panorama.

Mary in the lounge on Sylvia Earle's Deck 8, enjoying the view of the Brasvalbreen (Pan right to see the full panorama.)

Sailing past the southern seawall of the Nordauslandet ice cap, going east, after lunch on 2024 June 17th. I am outside the viewing lounge on Deck 8 of the Sylvia Earle, reflected (multiply) in the several-layer window. Also reflected is the ice wall behind me. Through my reflection, you can see Mary, enjoying the view in warm comfort, inside. We sat quietly there, deeply impressed by the enormous ice dome that covers the eastern part of Nordauslandet, Svalbard.

Glacier wall and ice blocks ready to fall...

This low point in the glacier wall lets us see up onto the glacier cap the covers Nordauslandet. We get a hint of the vast desolation that one would feel, inland, atop the glacier cap.

Northern fulmar in evening sunlight, after supper, as we sailed toward Kvitoya Island.

June 18 AM: Landing at Andreeneset, Kvitoya Island; PM: Sail Back to Southern Nordauslandet

Windy.com map that shows the site of John's AM landing at Kvitoya (Russian: "White") Island. We had a perfect day, with calm, sunny weather and temperatures in the mid-30s degrees F. It is a rare privilege to have such easy access to Kvitoya Island, which most often is cut off by pack ice, fog, and wild weather.

Panorama of Kvitoya Island on as wonderful a day as you could hope for. The island is covered with a perfect convex dome of ice. Having seen it and marveled at the perfection that gravity and slowly flowing ice can engineer, the feeling of immensity is far from completely captured by this iphone panorama. It was truly a privilege to experience this place. Doubly so, in fact: We were told during the evening briefing that, effective the start of 2025, Norway will drastically reduce the number of places in Svalbard where tourists and cruise ships can go. Going to Kvitoya will then no longer be allowed.

Also, the weather is rarely so friendly. Aurora expedition leaders emphasized how seldom they have been able to reach the island. Kvitoya also has significance for the history of polar exploration. Among many early attempts to reach the North Pole, one of the the strangest was an attempt to get there via hydrogen-filled balloon. Swedish explorer Salomon August Andrée and companions Knut Frænkel and Nils Strindberg tried this in 1897. Their balloon leaked badly and could barely be steered; it crash-landed after ~ 2 days, They managed to get to Kvitoya at its SW point, now known as Andréeneset. They endured their hardships remarkably well, considering the primitive equipment then available and especially their poor preparation: they did not expect to crash and had not supplied themselves for an emergency. They died there after a few weeks for reasons that are not understood. Their fate was a well known mystery for 33 years until, in 1930, their remains were found, including a journal and a tin box containing still-developable photographic film. Wikipedia (for example) discusses this history in detail.

John managed to be part of this expeditions' last landings before fog closed in, yielding the following pictures, including one of the concrete memorial to the Andrée expedition.

The landing site, seen from the ship via telphoto lens, gives a sense of the vastness of the scale.

Landing was convenient: they just ran the zodiacs completely onto the fast ice. (This picture was actually taken quickly just before I boarded the zodiac to go back to the ship: fog had rolled in -- we were being hurried -- and so the ship is not visible in the distance.)

Two-inch-wide crack through the fast ice. The tidal range here is about 1 meter, and the floating ice on which I walked to get to shore has to flex and break somewhere to accomodate the tides. I had no idea how deep the water was, here -- probably not deep at all -- but crossing this crack did feel surreal.

Same crack, running west from the photographer's shadow. It was clear that the crack widened in the 1/2 hour that I was on shore. There was no feeling of danger -- I must have been only about 30 feet from the nearest patch of exposed sand -- but it was interesting.

Memorial to the Andrée expedition: The inscription reads, in 4 lines, S.A.Andrée, N.Strindberg, K.Frænkel, 1897.

June 19 AM: Zodiac Cruise at Alkefjellat; PM: Skipped Landing at Wahlbergoya

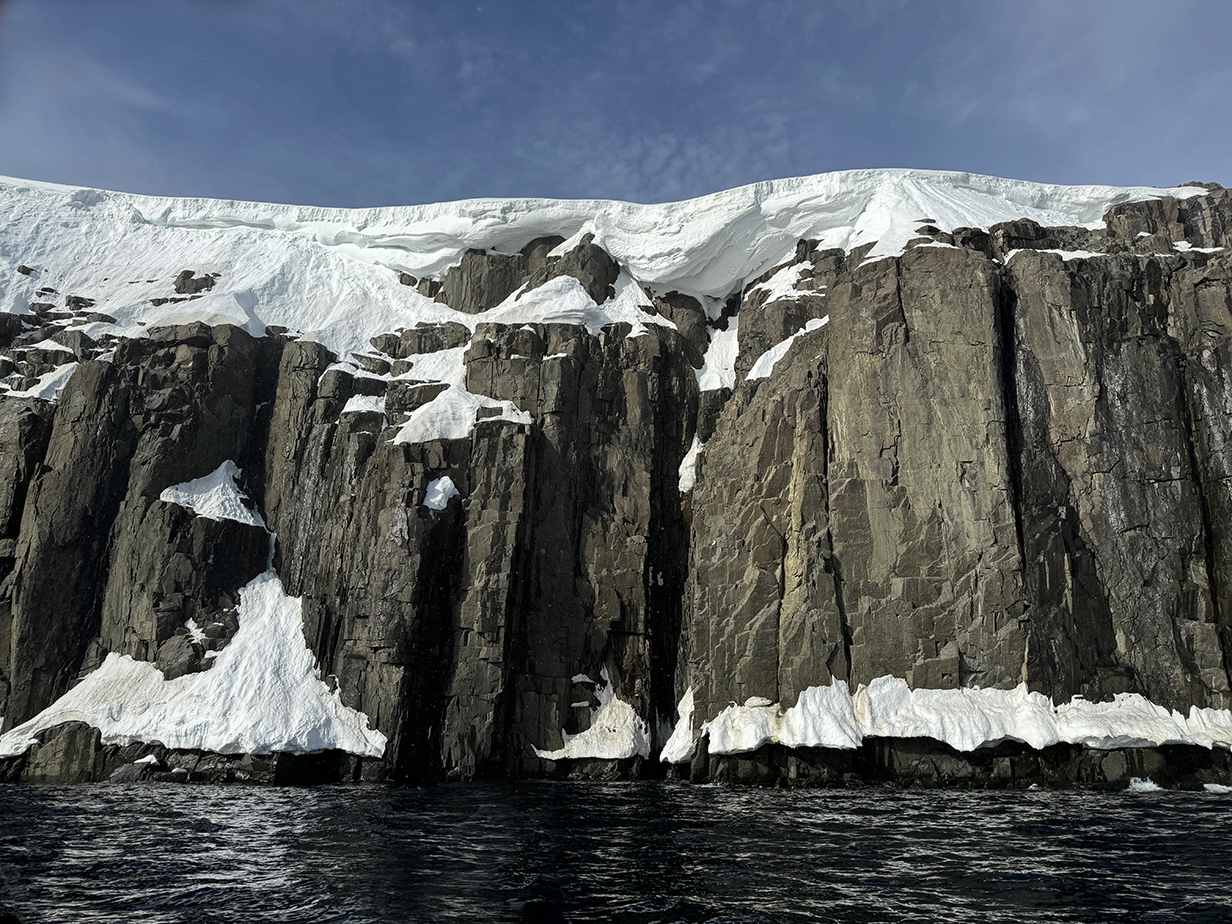

This morning's zodiac cruise was along the base of Alkefjellat, the most important bird nesting cliffs in Svalbard. The cliffs themselves are spectacular black basalt columns 300 or more feet high, with occasional intrusions of Jurassic dolomite that caused Permian limestone to re-crystalize as marble. There are both vertical fracture planes (which make dramatic columns) and horizontal fracture planes (which create perfect real estate for nesting birds). Around 60,000 pairs of Brunnich's guillemots are said to nest here. High on the cliffs, the predominant bird is Black-legged kittiwake. Occasionally we also saw Black guillemots, Northern fulmar, and one Barnacle goose. Bird droppings from above fertilize rich mosses and lichens on occasional lower slopes. They are ideal habitat for Snow bunting, which we heard but never saw. Near the end of our cruise, the weather turned unfriendly, with more wind and waves, some snow, and fog. Around this time, one of the zodiac passengers spotted an Arctic fox. I got fairly good pictures. About then, we finished following the most productive cliffs and headed back to the ship. That was the most vicious ride that I've had so far on a zodiac: by the end, essentially all of my winter clothes were wet. Luckily, the cameras were protected enough to be OK. But I skipped the PM landing as a result of getting uncomfortably cold and wet. Lots of pictures from this outing follow.

This was a specialty cruise for birders: we benefited from the expertise of zodiac driver and ship's bird guide, Graham ("Snowy") Snow.

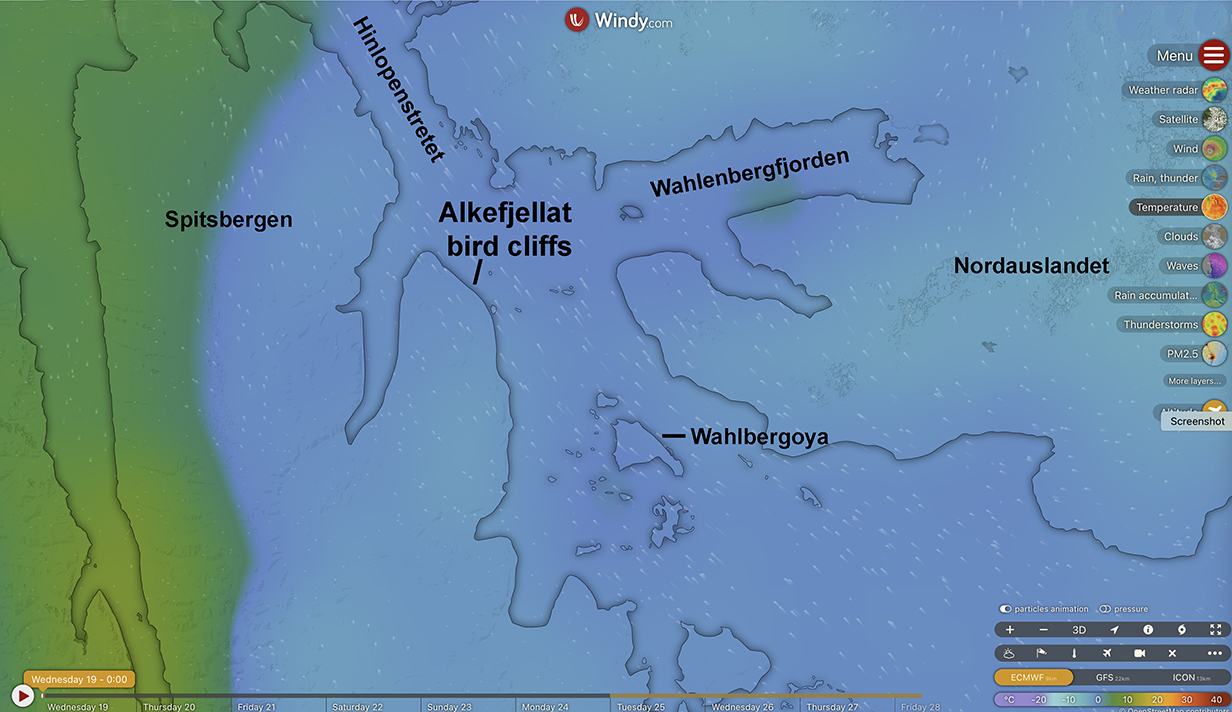

Location of the Alkefjellat bird cliffs

First impression was of massive, vertical, black basalt ... with a few ledges occupied by guillemots

Cliffs quickly became more dramatic, with deep embayments and lots more birds. In the bottom part of the cliff, almost all birds were Brunnich's guillemots.

Bird guide and zodiac driver "Snowy" and birders -- emphatically including me -- were thoroughly enthralled by the bird cliffs.

A zodiac in the foreground gives a sense of scale.

We saw one barnacle goose.

And one Black guillemot came close enough for a picture, early on.

Even before we got to the main colony, there were strikingly rich concentrations of birds on especially desireable ledges ...

... and in the water.

Brunnich's guillemot or (as in Clements) Thick-billed murre

Many pairs of guillemots were enthusiastically mating. The breeding season is well defined and short, so mating, brooding, hatching, and the rousting of half-grown chicks into the water (followed by and cared for, usually, by their fathers) are all synchronized.

Center of the colony -- it is easy to believe estimates that 60,000 bird pairs nest on these cliffs.

The sky was alive with birds all around the central concentration of the colony.

The Alkefjellat cliffs were so dramatic that I felt like I had fallen into an episode of Game of Thrones.

As we neared the end of the vertical section of bird cliffs, more and more scree slopes appeared, well fertilized from above, mossy, and reachable by Arctic foxes who hunt for birds and eggs. This is where we saw:

Arctic fox hunting on mossy slopes beneath the bird cliffs

One more view that shows almost-white marble intrusions at the tops of some cliffs and pinnacles

At about this time, winds, waves, and snowfall got markedly worse and we had a rather raw ride back to the ship. All my winter clothes got wet. So I skipped the afternoon landing ... which, I was told, was rather bland anyway. Still;

We saw another polar bear on one of the many small islands past which we sailed. This was clearly a female, because she wore a tracking collar. Male bears' necks are thicker than their heads, so they throw off any collar that might be put on them.

This was not a great view -- none of our views have been superb -- but, when you see how powerfully a bear grabs its prey, you understand why the expedition crew was careful not to get close. Besides, we ought not to disturb bears' lives.

June 20: Gyldenoyane and Faksevagen

Today was rather wrecked by poor weather (including rain) and inconvenient pack ice. The ship cruised around Hinlopenstretet, trying several options before landings were made. During the cruise, we saw one polar bear. I skipped the shore landings: Yesterday's long and cold zodiac cruise threatened to give me a cold, and I wanted to get over that before it got out of control. So far (evening of June 20) so good.

The captain, crew, and expedition staff continually looked for polar bears throughout the trip. Every sighting was broadcast to all and met with great excitement. Late this evening, we passed another bear, and the ship was immediately stopped to give everybody a look. This bear looks hungry to me. Svalbard cannot be an easy place for them to live, in summer, when there is virtually no pack ice and few seals. Here's an unexpected statistic for this trip: we saw more polar bears than seals.

Ironically, while we drifted past the on-shore polar bear, two Great skuas were sharing a meal out in the water, closer to the ship. It was only the second time that I saw this species.

June 21 AM: Zodiac Cruise to Texas Bar; PM: Zodiac Cruise to Monacobreen

June 21 was one of those perfect days that you hope for and don't often get in the arctic -- sunny, calm, and with temperatures a few degrees above freezing. In the morning, John took a very relaxed zodiac cruise around the bay and islands shown above. The main attraction was remarkably folded rock layers. There was also a brief stop at Texas Bar. By the afternoon, we has sailed farther south to the end of the fjord, where we had another zodiac cruise around the terminus of Monacobreen. The weather remained perfect.

King eider: This is my life bird. I had been looking hard for it throughout the trip. That's the good news. The bad news is this: Aurora cruises are not well designed for birding, and this picture is an example of why. Expedition practices put no strong focus on birding, and birders are not matched up with zodiac drivers who know birds. The only times I managed to go out with the trip's bird guide, Snowy, were when I made a special fuss connected with a place (e. g., bird cliffs) where prospects looked especially good. None of those occasions yielded new birds. That's not how you usually get rare birds. You have to be lucky, and you have to be (more or less) first on the scene. This day, like most days, my side of the ship was not called early to the mud room. I was one of the first people from my side and deck who got out in a zodiac. But it was about 5th -- 7th to head in the direction of the first target cove. And my zodiac driver was not a birder. OK: he or she did let us know that people up ahead were seeing King eider. But we made no special effort to get there. My immediate thought was: By the time we get there, they will have flown away. Sure enough, while we were still far away, I saw two birds flying away from the zodiacs up ahead. On a hunch, I got the above picture -- not good, but the best that I managed. I immediately saw that these were King eiders. So I got my life bird. But the picture is poor. Whereas somebody else -- I never knew who -- got an absolutely spectacular picture from very close.

Aurora does very well to provide broad experiences to generalists. It works hard and successfully to be fair to everybody in spreading out all the passengers to all the guides and all the target sites. But it is not well suited to the specialist birder. We have enormously enjoyed the generalist experience of seeing wonderful sites in safety and with guides who have broad expertise. But the lack of focus makes me wary about whether to invest in future trips with Aurora versus going on specialist birding tours. Although they, of course, have the problem that they may not have infrastructure to go to the hard-to-reach places that are Aurora's main venues.

In the end, King eider was the 5th and last new bird that I got on the two Aurora cruises. (I saw Rock ptarmigan and Glaucous gull before the Aurora cruises started.) That's not terrible, although several more were possible. Snowy was as helpful as he could be, given Aurora constraints. But I was also lucky: e. g., only I saw Ivory gull. I am glad that I saw what I saw. But I have to think hard about future trips. How I got King eider was a major disappointment.

The rest of the morning was a generalist's delight:

Views were magnificent. "Spitsbergen" is rightly named, and every major valley contains a glacier. But look how rock composition can change radically in only a short distance. Spitsbergen is a crazy mix of geological histories.

We got our closest look so far at a polar bear -- a female wearing a collar. Mostly, she slept. Once in a while, she sniffed the air to check out her environment.

We made a brief stop at the "Texas Bar" -- a tiny refuge in a vast wilderness.

OK, the irony: We have lived for 24.5 years in Texas and this is the first time that I have been to a Texas Bar.

Panorama of the inside of Texas Bar -- well stocked. This place is a refuge hut for hunters, trappers, scientists, adventurers ... and cruise passengers. A rest stop that is safe from polar bears means a lot, out here.

Of course, the Sylvia Earle team made sure that no polar bears were around.

After that, we made a leisurely cruise around the nearby bays.

Common eiders in the snow -- hardy birds in a tough environment

Pink-footed geese (The top picture gives context -- the wonderfully varied landscape of lichen and moss, spring flowers and harsh rock. The bottom picture is a cropped version that better shows the birds.)

This is the top-left corner of the larger-field picture above -- it shows the wonderfully delicate, colorful, and detailed flowering of the tundra spring.

Purple saxifrage was, throughout the trip, the most obvious and most beautiful flower of the spring tundra.

In include this picture with a zodiac in it to give a sense of scale for this morning's scenery. We were often very close to rock faces, and they generally were not big. So the morning cruise felt unusually intimate. This was very special. The attractions were the rock formations.

The coves around which we cruised were a marvelous history of geological processes that torture rock into fantastic shapes. All these layers were laid down horizontally by the slow accumulation of debris at the bottom of an ocean or sea. Diffferent layers may have different origins; e. g., volcanic ash in short eruptions versus slow annual accumulation of debris. Then these layers had to be subducted deep under the surface of the earth to where temperatures were high enough to make them plastic and pressures were high enough to fold them into a marvelous shapes. We see acute angles, S-shaped distortions, and even complete, almost-180-degree folds. At the same time, conditions were not so extreme (that is, the rocks did not melt into magma) such that the coherence of the layers was lost. Immeasurable times later, the now-metamorphic, folded layers were transported back to the surface of the earth. Then they were carved -- e. g., by glaciers -- in such a way that the folds now form the surfaces of the coves that we see. And these processes must be at least moderately common, because we have seen such tortured rock -- not as extreme as here, usually -- in many places in the world, including South Georgia Island and the Himalayas.

Seligerbreen from our balcony before the afternoon zodiac cruise. If I understand online maps correctly, this side-glacier was still merged with the larger Monacobreen to its left (from this direction) until the 2010s. Now, both glaciers have retreated enough so that they separately end at Liefdefjorden.

This is an 180-degree panorama from our balcony before the afternoon cruise. Seligerbreen is on the right; Monacobreen is on the left, and our zodiac cruise crossed the front of both glaciers from right to left. These pictures were taken with my iphone. More detailed pictures taken with my Canon R5 camera and 100-500 mm telephoto lens follow.

Approaching the east end of Seligerbreen -- still in perfect weather -- near the start of our afternoon zodiac cruise. Lots of ice in the water: small bits must often calve off of both glaciers.

The phantasmagorically ready-to-crumble face of Seligerbreen

Seracs on the face of Seligerbreen

Bearded seal

Now approaching Monacobreen in the middle of the afternoon zodiac cruise

Dramatic seracs in the face of Monacobreen

Seracs in Monacobreen

In Monacobreen, in many other glaciers in Svalbard, and in many glaciers in Antarctica, I have noticed a persistent tendency to form short, arched tunnels like this one. I have not found a convincing explanation, either online or from glacier experts on my voyages. I suspect that there is a simple explanation, but I don't know what it is. What they seem NOT to be is the ends of under-ice rivers where meltwater flows through the ice to what eventually gets sheared off as the glacier's edge. Under-ice rivers happen a lot ... and yet, I have never seen a convincing example of such a sheared-off tunnel. It should be morphologically a lot like a lava tube. And those, we certainly have seen in young and old lava flows. Although again: not at water's edge.

During the zodiac cruise, we saw several calving events, where small pieces fell off the Monacobreen, leaving behind this very blue section of pristine glacier ice.

Arctic skua = Parasitic jaeger

This hanging glacier in a small side valley looks very clearly to be making a terminal moraine as it melts.

Icebergs can melt into a fantastic array of shapes; e. g., these flutes.

End-of-the-day location of Sylvia Earle as displayed on the cabin TV. This is how I kept track of were we were. The ship is at 79 degrees 31 minutes 19.2 seconds north latitude and 12 degrees 29 minutes 57.8 seconds east longitude as displayed on the TV.

Almost every evening after supper, I was out on our balcony photographing birds. Almost always, the same few species came by, most often Northern fulmar, like this bird.

Today was an especially beautiful day.

From the morning of June 3rd (we crossed the arctic circle at 9 PM that night) and throughout the cruise via Jan Mayen to and around Svalbard until the evening of June 24 in Oslo, the sun was always above the horizon. I intended to take a "midnight sun" picture during this time, as I had done the last time we were above the arctic circle in Finland and Norway in 2006. But I never woke up around midnight. This picture is the best that I managed, at 2:14 AM on June 22, while we were sailing around the north end of Svalbard as shown on the map, below. The picture is taken looking north. The sun would have been almost this high at its lowest point of the night: we were at about 80 degrees north latitude.

June 22: Svalbard: AM: Zodiac Cruise at Fuglefjorden; PM: Landing and Zodiac Cruise at Magdalenefjorden

This morning in perfect weather (calm, high 30s deg F), we took a zodiac cruise around Fuglefjorden (red dot on Windy map, above). The intent was in part to see -- up close -- the glacier at its head. As we neared the glacier, I am confident that I photographed King eider from far away: its head shape with concave forhead is unmistakeable. Then somebody radioed "polar bear", and we immeditely turned around and zoomed for the bear. This was, on one hand, disappointing for me, but on the other, I have to admit that we got our best look of the trip at a male polar bear. I even got a short movie of him entering the water and swimming.

Fuglefjorden from the balcony of our suite. Scroll right to see this 180-degree panorama.

Fuglefjorden and its glacier from our suite

Spitsbergen mountains on the west side of Fuglefjorden in morning sunlight

More-than-180-degree panorama showing the head of the fjord and the glacier in front of our zodiac and all the way around behind us to the north end of the fjord and the island beyond (see the above map). The immensity of the landscape was profound.

"Spitz Bergen"

Textured snow slopes ...

A harbor seal -- very inquisitive -- swam all around us even while diving to hunt.