John and Mary Kormendy: Seabourn Cruise 2025

This web site contains the pictures from our 80-day Seabourn Cruise from Darwin, Australia, west and south to Broome, Australia, then back to Darwin and on via Indonesian New Guinea, Papua New Guinea, the Solomon Islands, the Santa Cruz Islands, Fiji, Tonga, Samoa, the Cook Islands, French Polynesia, including Tahiti, Pitcairn Island, Ducie Island, Easter Island, and the Juan Fernandez Islands, ending up in Santiago, Chile.

The trip and this web site are finished -- at most, I may add a few more pictures.

The whole 3.5-month trip including stops in Paris, Singapore, and birding in NW Australia (links at the end

of this posting) was epic, with an enormous variety of wonderful (and a few not-so-wonderful) experiences.

We enjoyed it immensely. John took part in many excursions off the ship, concentrating on nature and often

birding with private guides while ship's passengers did something else. Mary is handicapped by crippling

back pain that results from many marathons and other long walks. She mostly enjoyed the wonderfully

comfortable life on the ship, seeing what she could from the ship and taking part in 2 off-the-ship

excursions, the Mitchell Falls helicopter tour on August 29 and our submarine dive on September 30.

Together with the pre-cruise stops in Paris, Singapore, and NW Australia, this was a once-in-a-lifetime

extravaganza.

Or maybe not. We would be happy to do something like this trip again.

The purpose of this web site is to catalog our memories, not to showcase the trip for public readers. So I include pictures that are not very good when they document sightings that are important to us. All pictures are copyrighted and should not be used for commercial purposes without our permission.

Itinerary and Maps

This shows the itinerary of the second part of our cruise, from August 24 in Broome, Australia, until October 30 in San Antonio (near Santiago), Chile. The first part of our cruise from August 13 to August 24 visits the same places from Broome to Darwin but starts in Darwin and does them in reverse order.

This map shows the part of our Seabourn cruise from Broome, Australia to the Solomon Islands. We chose to begin our cruise in Darwin, Australia, and first cruise from Darwin to Broome with all the stops shown here but in reverse order. They are then repeated on the day numbers of our (formally separate, second) cruise from Broome to Chile. The numbers printed in dark red before each destination name are day numbers out of Broome. Printed in bright red are places where we birded during our 2022 July-August trip to Australia and Papua New Guinea -- see this web site for pictures.

This was an "expedition cruise" with exact itinerary dependent to some extent on conditions like weather and (twice) on the need for ship's maintenance in ports (Darwin, in the middle of the trip, and Fiji). So the exact route and dates of our various stops sometimes were changed in real time, usually by 1 or 2 days. For example, the sea day between Ashmore Reef and mainland Australia was eliminated in favor of an added stop at Kuri Bay. I skipped that excursion. We stayed for 2 days extra in Pape'ete; this was actually a great benefit, because it gave me more time to bird. So the schedule in the maps is not quite correct. Web site postings give correct dates.

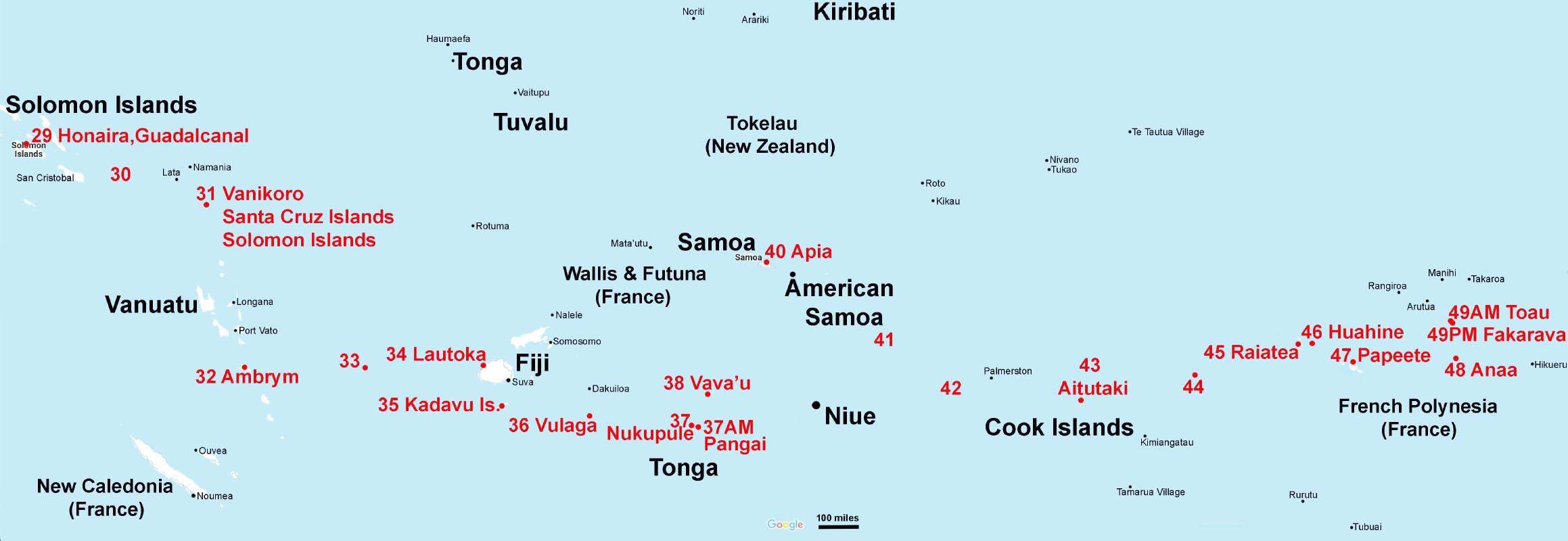

This map shows in more detail our destinations during the next part of our cruise, from the Solomon Islands to French Polynesia. Again, red numbers are day numbers starting with 0 in Broome, Australia. It's a wide map: scroll right to see the full panorama.

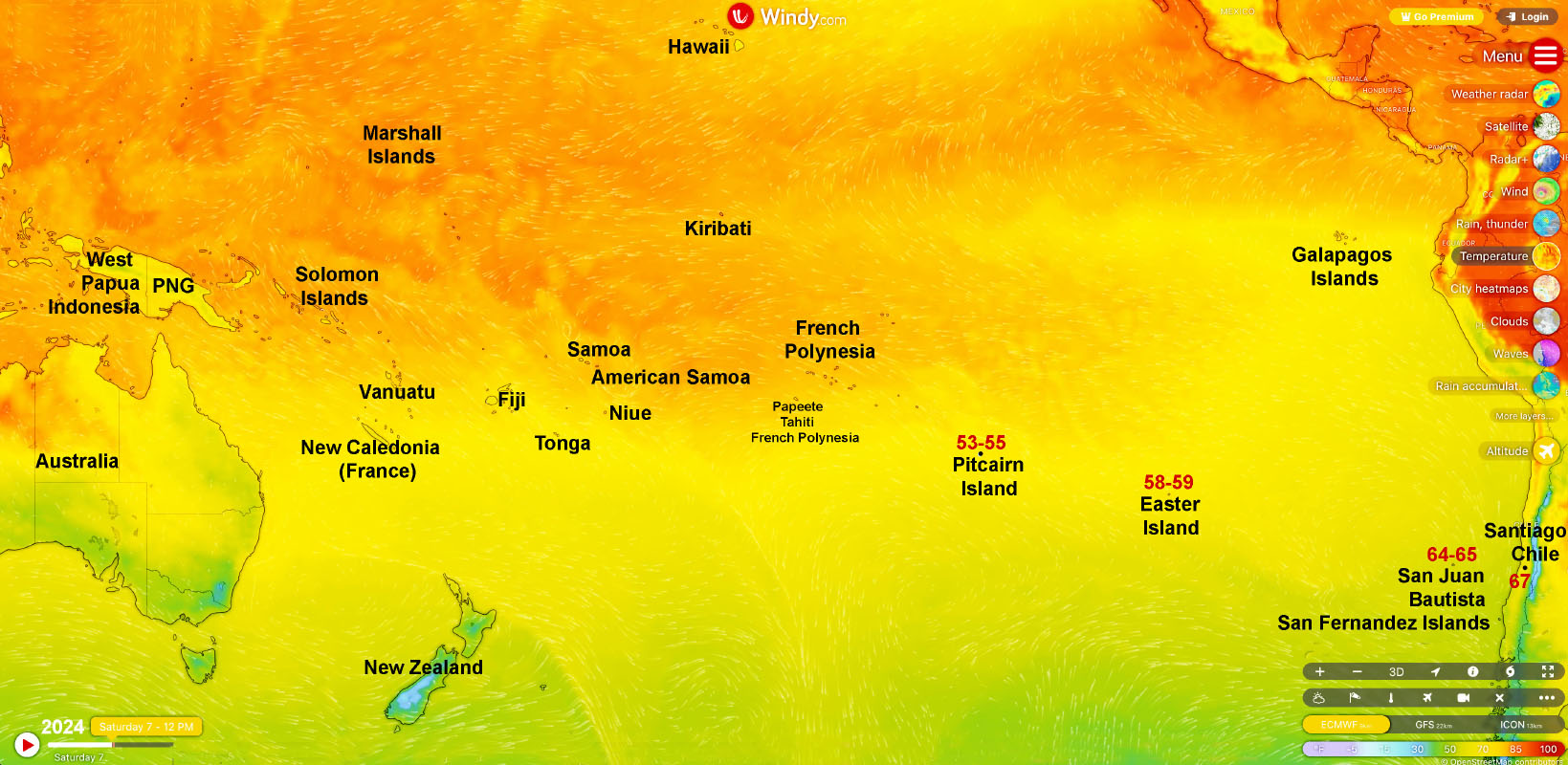

To see the relative locations of the last stops on our cruise, we need to shrink the above maps by a lot. The resulting shows destinations from West Papua Indonesia and Papua New Guinea all the way to our final docking in San Antonio, the port of Santiago, Chile. This map was made from the "Windy Waves" web site encoding surface temperature. "Windy Waves" is a superb tool to check weather and sea conditions, especially during an ocean cruise but useful also to check (e. g.) temperatures and rainfall on land.

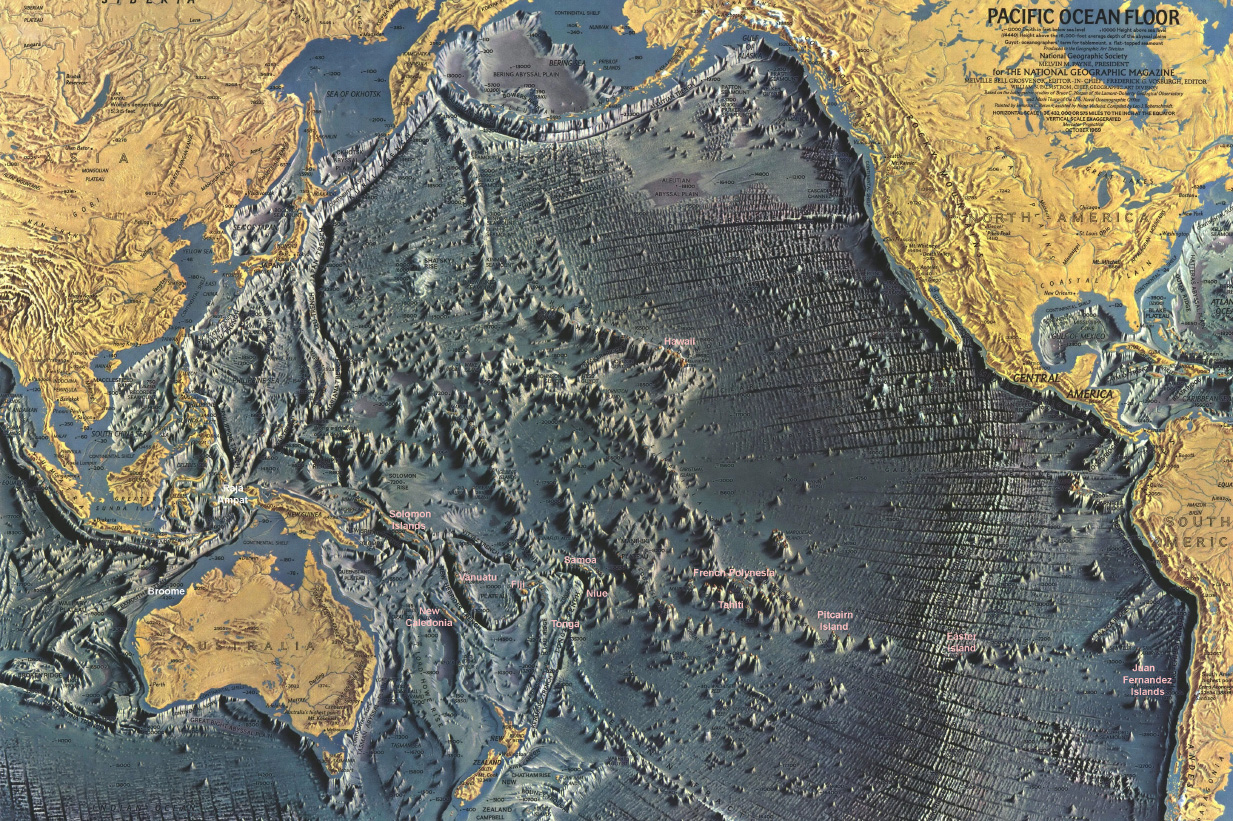

This shows many of our destinations on a relief map of the Pacific Ocean floor published many years ago by National Geographic. Most islands that we visit are the tips of volcanoes, sometimes in isolated burn-throughs of the Earth's crust and sometimes parts of mountain chains of volcanoes. It is remarkable how many times volcanoes have burned through the relatively thin Earth's crust that makes up the ocean floor. This map wonderfully puts our destinations in a global geoplanetary context.

Trip Bird

Tahiti monarch (October 12, 2025, near Pape'ete, Tahiti)

This is probably the second-rarest bird that I have ever seen. Whacked by many threats, the world population (uncertain because some of its habitat is hard to explore) was recorded in 1997 as 21 birds. Aggressive protection has helped it to increase to an estimate of 25-100 adults in 2019 and 100-200 birds now. I was fortunate to be guided in the (closed to the public) Tahiti Monarch Preserve, Captage Papahue, by two dedicated wardens. I saw and photographed 4 birds, two very well and 2 at greater distance. Having had the experience of looking for similarly threatened and rare forest endemic birds in Hawaii, this sighting means more to me than most others, during this trip and elsewhere.

Scenery and Birds

August 15, 2025: Koolama Bay and King George River and Falls zodiac cruise

Our first stop was at King George River, SW of Darwin. The ship provided this map of the route of our 20-nautical-mile zodiac cruise up the tidal part of the river to the famous twin falls. Actually, I took this cruise as part of a photography course let by ship's photographer Harry Aslan Rogers. We first cruised up the mangrove-sided channel toward the bottom-left of the main river channel starting near its mouth. Went in as far as we could, until the left- and right-side mangrove banks merged. Then we cruised up the main river to the twin falls. This gave us a wonderfully detailed look at the ornate landscape and its wildlife. Especially the birds.

This is a more-than-180-degree panorama of Koolama Bay, the entrance to the river gorge. Here and throughout our zodiac cruise, the scenery was spectacular. Pan right to see the full pano.

Cliffs near the entrance to King George River. The "Warten sandstone" rock layers are approximately 1.8 billion years old: younger layers atop them are eroded away. These layers encode -- and overwhelmingly emphasize -- many millions of years of the history of this ancient place. They are amazingly ornate: see pictures that follow.

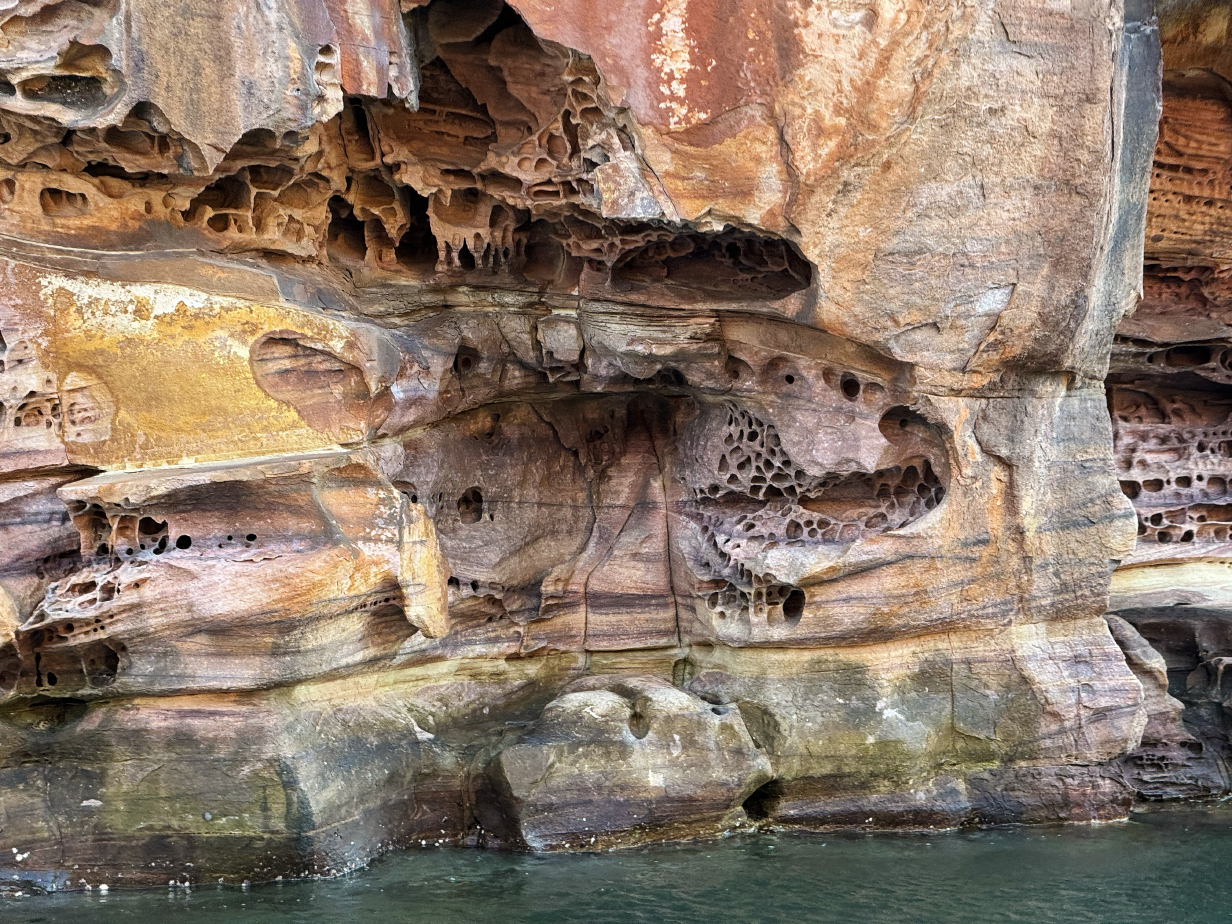

The complicated interaction of salt water spray, wind, and waves creates a marvellous 3-D tapestry of erosion -- captivating artistry everywhere you look, especially near water level. We were there at high tide, so there must have been much more of it under water.

This is the cliff top that towers over the previous two pictures.

Entering the King Goerge River gorge from Koolama Bay (scroll right to see the full pano)

Australian darter drying its wings

Osprey on a nest mid-way up the wall of the King George River gorge -- very safe and a very good place to make a living. We saw several Osprey and Peregrine falcons on nests, in the latter case (but not photographed) with 2 chicks.

White-faced heron

More 3D art, farther upstream

Ship's photographer Harry Aslan Rogers taking pictures of a precariously positioned rock known as "the guillotine' ... again, amid marvels of 3D art

This shows the guillotine.

Tenderness of tree and rock

Sacred kingfisher

I found the artistry of the gorge walls irresistible.

These are the twin falls of the King George River, almost dried up, now, during the height of Northern Australia's dry season. The height of the falls is variously quoted as 80 - 100 m or 262 - 328 feet, presumably because they fall into a tidal river. I think that these are overestimates, and lower values can be found on the web. We were there at high tide, when the falls are less high than at low tide. The black color of the walls is due to cyanobacteria, which thrive when the falls are most active and which hang on and survive during the dry season.

King George river dry waterfall and (in shadow to the right) a zodiac at the same distance, for scale

The trickle of water that still flows during the dry season has cut a narrow niche for itself in the wall of the main waterfall.

Rainbow ... if you catch the sunlight just right

View of the King George River gorge from the twin falls back out toward the mouth of the river

Mertens water monitor (Varanus mertensi) on the way back to the ship

August 16, 2025: Vansittart Bay landing

Brolga -- one of three on the sand flats at our Vansittart Bay landing

Brown honeyeater was the most common honeyeater throughout the Northern Territory and Australian cruise portions of our trip. This was at the water hole at Vansittart bay.

White-throated honeyeater at the water hole

Yellow-tinted honeyeater (The yellow plume to the right of the black crescent at the ear is a bit too overexposed to be obvious.)

Yellow-tinted honeyeaters

Double-barred finch was the most common bird at the water hole.

August 17, 2025: Ashmore Reef zodiac cruise

Ashmore Reef is a major nesting site for pelagic birds, a stopover for migrating birds, and a marine sanctuary. Unfortunately, no arrangement was made for me to take a zodiac with the ship's most experienced birder and photographer. This was disappointing. I could potentially have gotten 2 moderately easy and several harder new birds. On my own, with limited time and a non-birder (but otherwise helpful) zodiac driver, I saw only 3 bird species and got only one new bird, the easy and distinctive Bridled tern.

Brown booby was by far the most common bird around us in shallow water inside the reef and near the nesting island.

Common noddy also was easy. In fact, it was a life bird for both of us, despite the fact that we have been in the Common noddy's range many times. Also, I was hoping for Lesser noddy, but they are rarer and, among the relatively few birds that came close to our zodiac, I never saw one.

Bridled tern (This is my life bird. I saw several; they were clearly the most common tern -- at least just now -- at Ashmore Reef. The white eye stripe that extends well back behind the eye is characteristic.)

Ship's photographer Harry Rogers and our photo group zodiac driver

August 20 AM, 2025: Mitchell Falls helicopter tour from Hunter River

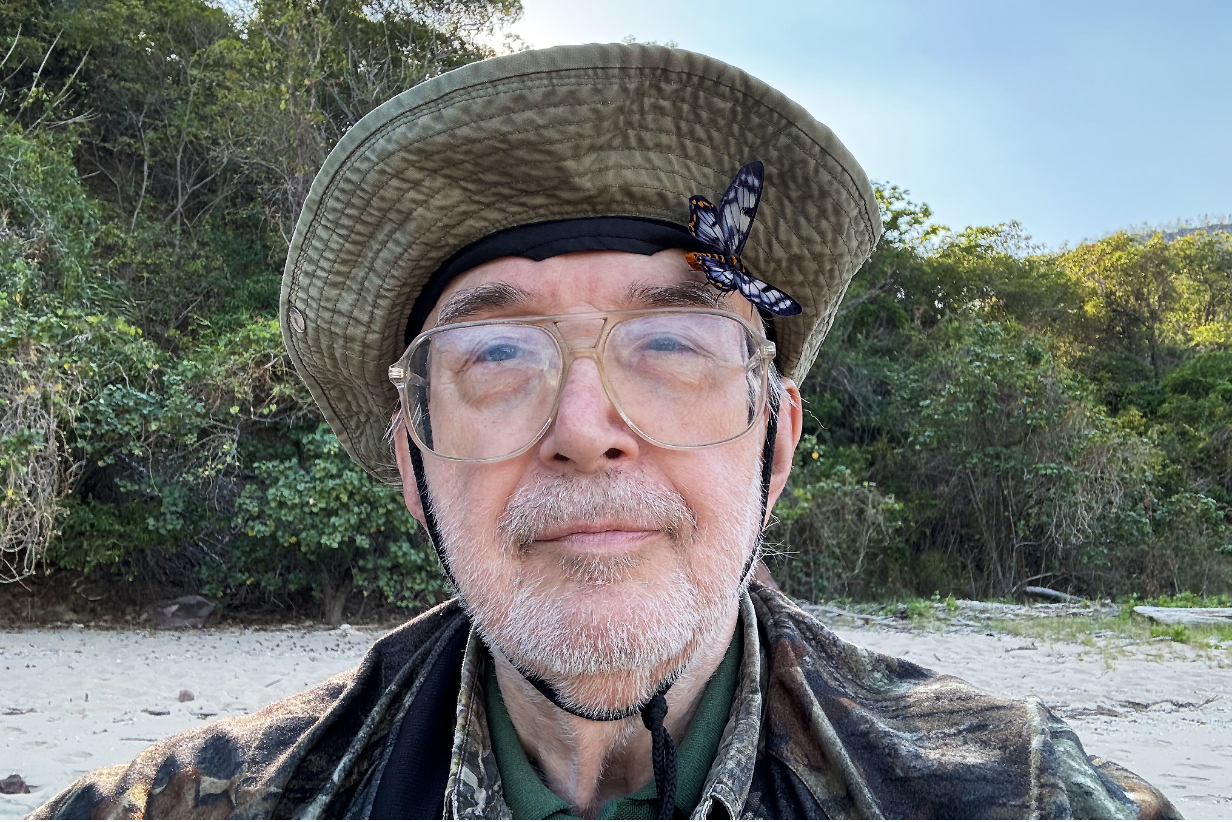

While I waited for the arrival of the helicopters that would take us to Mitchell Falls, this butterfly landed briefly on my face, presumably in search of salts. It looks most like a Dainty swallowtail (Papilo anactus). The range map for this species shows it only on the east coastal side of Australia "but with potential for vagrants in the Kimberley". If readers of this page can definitively ID it, please email me at kormendy at astro dot as dot utexas dot edu. Thanks!

The left helicopter took me (John) to Mitchell Falls. Mary had a bad cold and skipped this outing, so only 4 of 5 seats were occupied. I was lucky to get the right-hand back window seat, with the result that I could get good pictures during the roughly 20-minute flight.

View of the cockpit from the right-hand back seat. The passenger is photographing Seabourn Pursuit, moments after takeoff.

Seabourn Pursuit from the helicopter ride. Our suite during the Darwin-to-Broome part of the cruise is at the front of the deck immediately above the deck that extends to the bow, slightly overhung by the bridge deck and on the far (i. e., port) side of the ship, facing forward. Wonderful suite with wonderful views. On the rest of the cruise, from Broome to Santiago, Chile, we will be one floor farther up, also on the port side, immediatly aft of the bridge and therefore on the back side that is hidden in this view. This gives us a side-facing balcony, which is actually better for pelagic birding.

Kimberley coast from the helicopter

Rocky highland scrub forest gives way to mangroves in river valleys.

More views from the helicopter -- mangrove serpentines

Approaching Mitchell River and falls

Upper Mitchell River, which flows from right to left in this picture. The triple waterfall is at the head of the gorge at upper left.

Mitchell Falls from the helicopter

Now from our landing site, these are circular basins around 10 feet in diameter, upstream from the falls. They are produced during periods of flood flow by circular eddies that carry rocks which scour the basins. I have seen similar -- but less dramatic! -- basins more than 60 years ago along the Niagara River in eastern Canada.

Panoramas of the first view of Mitchell Falls from near the landing site. Scroll right to see the full pictures.

Mitchell falls -- simply gorgeous (movie)

Upper 3 Mitchell falls (Here is a movie that better captures the moment.)

Lower Mitchell falls

During the helicopter flight back to the ship, we were treated to a "bonus" view of 90 m Donkins Falls on the Hunter River.

August 20 PM, 2025: Hunter River -- Porosus Creek zodiac cruise

The afternoon, detailed "Image Masters" zodiac cruise was on Porosus creek. The Australian saltwater crocodile is Crocodylus porosus, so it is not hard to guess the main attraction.

Mudskippers were everywhere. We saw many confrontations over status, territory, and mating rights, no less ferocious for being between ~ 2-inch-long fish.

Mangrove robin -- good bird; well seen

Croc alert!

August 21 PM, 2025: Montgomery Reef zodiac cruise

At the beginning of our zodiac cruise, it felt like the top of the reef -- this part, anyway -- was just awash. But the tide fell quickly, and within an hour, about 4 m of the reef were exposed, and fast rivulets could not keep up in draining the reeftop. Some sea life gets stranded; other creatures try to escape, and predators such as birds and even reef sharks feast on the unlucky. Dominating the spectacle are torrents of shallow waterfalls as the reef continues to drain. As documented below:

A reef shark was momentarily stranded as it lunged after prey. It quickly flapped its way back into deeper water ... and then continued to hunt as the tide continued to drop.

Pied oystercatchers

Beach thick-knee (or Stone-curlew)

Gradually, dozens of waterfalls emerged as the tide continued to drain off the reef. The zodiac provides a sense of scale.

A movie provides a better sense of the feel of the tidal drainoff.

August 22 AM, 2025: Cyclone Creek zodiac cruise

Ship's photographer Harry Aslan Rogers (characteristically exuberant) and John (characteristically subdued) at the start of today's zodiac cruise to the spectacular rock formations around Cyclone Creek. Harry's Image Masters program gave five of us longer and more intimate excursions into nature plus excellent advice on photography and especially on finesse with the features of iphones and other cameras. Thanks also to Harry for tweaking the Image Masters' schedule to give me more chances to see new birds.

Cyclone Creek cliffs in early morning sunlight were a riot of color.

In the King George River valley, sedimentary strata were horizontal, but at Cyclone Creek, the layers that encode millions of years of sedimentation have been tilted -- here almost vertically -- or even crunched up into curves. Also, you can also see the consequence of arriving at low tide; many vertical meters of cliff are stained and covered with micro-organisms up to various high tide lines. Tidal ranges in the Kimberley are extraordinary, ~ 33 feet during spring tides and still ~ 12 feet during neap tides.

I hope that my photo co-conspirators -- including ship's photographer Harry -- don't mind if I post a picture of our group to record the feeling of tranquility inherent in the intimate connection with nature that was provided by the in-depth zodiac rides of our Image Masters Photography Masterclass.

Alcove in a cliff with trees makes for a charming moment in a memorable morning.

More tilted layers

Osprey ... far away

Spectacular rock formations ... including this movie.

More spectacular rocks and another movie to try to capture some of the feeling of sailing up Cyclone Creek .

Some layers are not just tilted -- they are squeezed up into rock waves.

The ubiquitous Brown honeyeater looks a bit different here ... or maybe this is just a juvenile.

Croc alert!

Mangrove robin

White-quilled rock-pigeon (I got my life bird just recently, during our Australian North End birding tour, on August 9th.)

August 23, 2025: Lacipede Island zodiac cruise

Today was promising: Lacipede Island just north of Broome is said to be a major nesting site for Roseate tern and could also have lesser Noddy, both of which I need. As it happens, I saw hundreds of Brown noddies and many hundreds of Brown boobies ... but no Lesser noddy and no Roseate tern. So today was a bit disappointing, despite the happy richness of more common birds. Still I got better pictures of Bridled tern than I did at Ashmore Reef.

Lacipede Islands Nature Reserve (with dark-morph Eastern reef-heron and Brown booby)

I tried to look at every one of the several hundred noddies that I photographed, but as near as I could tell, essentially all of them were resolutely Brown noddy. Note the sharp edge to the light gray cap at a line from the top of the bill to the eye. Below that line, the color is very dark. A few birds were brown all over. But none showed light gray between the bill and the eye, shading into brown only lower down on the chest. So I did not get Lesser noddy. And this was by far my best chance of the trip.

This cropped version of the above picture better shows the sharp line between bright above and dark brown below the line that connects the top of the bill with the eye. Hence: Brown noddy. Note how different birds have bills of different lengths and different amounts of decurvature. Hard to ID using bill length, as bird ID books suggest.

Brown noddy closeup to show colors between the bill and the eye

Bridled tern (The white eye stripe clearly extends back behind the eye.)

Caspian tern (non-breeding adult)

Brown boobies

Brown booby chick

Lesser frigatebird

Sacred kingfisher ... is not exactly to be expected on Lacipede Island. It surely did not get here "on purpose". On the other hand, this IS a place where a kingfisher might make a reasonably good living. But not a place where one might one day find a mate.

August 24, 2025: Broome

Today, we docked in Broome and formally switched from our Darwin-to-Broome cruise to our

Broome-to-Darwin-to-Santiago, Chile cruise. With much appreciated help from VENT's bird guide

Scott Baker, I had arranged to bird with Karina Sorrell

Mangroves and ornate rock formations at Roebuck Bay near Broome Bird Observatory (Scroll right

to see the full panorama.)

Mangrove fantail at "One-Tree" in Roebuck Bay (This is my life bird.

We got there just in time to benefit from the end of the "morning rush" ... plus the tide was

rapidly rising and driving us farther away from the mangroves. The spring tidal range here is a

remarkable 10 m; we were here less than a week before spring tide. Every few minutes, we had to

take a step back, farther up the beach, as the tide advanced.)

Dusky gerygone at "One-Tree" in Roebuck Bay (This is my life bird. It is a classic example

of a "little brown job" that is very hard to find and still harder to identify without a

guide.)

Sacred kingfisher

Silver gulls on what's left of the ornate rocks at Roebuck Bay at high tide

White-bellied sea eagle during the drive back to Broome

Gray-headed honeyeater was surprisingly easy and clearcut at the busy parking lot of Entrance Point

in Broome. This is my life bird.

Singing honeyeater, also at Entrance Point. This is a bad picture, almost directly up-sun,

but I include it because I may never have photographed this species before, and besides ...

it seems to have its eye on the prize.

Dusky gerygone one more time, in the shadows at Streeter's Jetty in Broome. By this time, the

tide was well on the ebb, and then, in mid-afternoon, bird activity got very subdued.

Mangrove fantail also one more time ... in a not very sharp picture in the shadows during the

heat of the day.

Meanwhile, the tide had gone out enough to expose the mud flats at Streeter's Jetty, so the

Fiddler crabs were out in force, trolling for mates. At this point, we declared the end of an

enjoyable and successful day. Many thanks to Karina for getting me the two target species

and the important bonus of Gray-headed honeyeater.

Today, John took the Mitchell Falls helicopter tour again, in part because, well: it's worth it ...

and because we wanted Mary to experience it, too. The weather was again perfect; the zodiac ride

to the helicopter takeoff and landing site was short and easy; the helicopter ride itself was again

very nice (this time, the tide was low and mud flats were exposed everywhere along Hunter river),

and the walk from the landing site at Mitchell Falls to the first, main lookout was not too hard

for Mary.

Mary at Mitchell Falls lookout: Red Bull gives her wiings. (Maybe not "wiiings", but still helpful.

Unfortunately, two cans would not give her wiiiiiings.)

Mary at the lookout to Mitchell Falls (Scroll right to see the full 180-degree panorama.)

Mitchell Falls (except for the uppermost falls) movie.

Bits of riparian habitat upstream from the falls: I heard bird song on my previous visit here,

so I looked for birds this time (specifically: Kimberley honeyeater), but we were scheduled too

late in the day for birding, and in the noon heat, the area was silent.

Red rock is characteristic of the Kimberley. This picture is exactly as taken with my iphone:

I have not changed the color balance, vibrance, or color saturation. The rock really is this

beautifully red.

Today, we stopped again at Ashmore Reef, on the way back from Broome to Darwin. I again took a

standard zodiac cruise with 11 other passengers. The zodiac driver was a good generalist but

had no special interest or expertise in birds. As expected, the result was a disappointing

ride. We were not allowed close to the islands where birds breed (this is, after all, a nature

reserve); we saw few birds, and only Brown boobies came close. I saw only a few, very distant terns,

mostly Common noddies and a few probable (but not confirmed) Bridled terns. No Roseate tern.

No Lesser noddy. Today was probably my last semi-realistic chance for Lesser noddy.

West Island at Ashmore Reef (This is the closest that we could get, photographed with an 800 mm

telephoto lens. The highest-flying bird is an adult Brown booby: adults were substantially

outnumbered by immatures.)

This was the only Common noddy that came close enough to be well photographed. Looks juvenile.

Immature Lesser frigatebirds were common during this zodiac cruise. I saw a few distant adults ...

but signs clearly were that we are here late in their breeding season. I suspect that the same is

true for other breeding sea birds. The end of August is not the best time to visit Ashmore reef.

Immature (probably Lesser) frigatebirds of various ages. The one with the white head is youngest.

Immature frigatebird (not sure whether this is Great or -- more probably -- Lesser) and

Brown booby (at least almost an adult)

Brown boobies were, like last time, by far the most common bird. They took an active interest in us,

and it was easy to get almost within arms length of birds sitting on buoys. Note again that all these

are immature birds.

Brown boobies (immature)

Today John again took the zodiac cruise up the King George River estuary to the twin falls.

This time, it was not an Image Masters cruise but just a normal (and therefore quicker) zodiac

excursion. I was again mesmerized by the 3-D artistry of erosion on the sandstone walls ...

but something went wrong with my iphone, and it erased all pictures taken before I arrived

at the falls. The following 3 pictures were taken with my birding camera. Pictures that follow

were taken with my iphone.

Artistry of erosion on the sandstone walls of the King George River gorge

The sea level estuary of the King George River ends about 7.5 miles upstream at the double falls.

Which are almost dry during the Northern Territory dry season. This shows the (black-walled) double

falls. Scroll right to see the full panorama.

King George River falls

Two views of the eastern wall of the river gorge near the falls

One more view of the western falls -- the one that was in sunlight -- before we headed back

to Seabourn Pursuit

And a last look at the east falls, now partly sunlit

This is the view back downstream away from (but still from near) King George River Falls.

More 3-D erosion art, this time on the east wall of the King George River gorge, on our way out

It is interesting how differently different rock faces are eroded. Presumably this results from

slight differences in composition and (e. g.) hardness ... because all this happened after the

various blocks were in place with respect to each other and all presumably had similar experiences

with eroding forces. It is also safe to assume that chunks sometimes break off the wall, taking

with them eroded faces and leaving behind a smooth surface. For all these reasons and maybe more,

results differ dramatically from block to block.

I can't resist adding one more ...

Everywhere we look, the walls of the gorge encode many millions of years of history.

From here, we zoomed back to the ship ... after a welcome second immersion in this wonderful experience.

This was the last stop in our return cruise from Broome to Darwin.

We docked in Darwin on September 3, stayed overnight, and sailed for West Papua Indonesia on

September 4. On September 3, we were offered a "birding tour" to Fogg Dam Conservation Reserve,

and I took it in the (admittedly faint) hope that I might see Pictorella manakin in the places where

we saw finches last time we were here, many years ago. This tour was not a success. The main visitor

center was closed; the backup viewing area was closed, and we got a chance to visit only one

~ 1 km walk to some wetlands plus a drive over the dam itself. I saw no finches.

Little bronze cuckoo was the best bird of the day, kindly pointed out by a birder from

the ship's crew.

Agile wallaby

Plumed whistling duck -- lots!

I think that this is a Whistling kite. Please email me if I am wrong. Thank you.

Today involved one the the hardest shore excursions of the trip and very likely the most

spectacular cultural experiece. It required an almost 13-mile zodiac ride, half of it from

the ship to the SE coast of mainland West Papua New Guinea and the rest up a river bordered

by rain forest to an Asmat village called -- we were told -- Uwus. The village is build on

stilts over a muddy swamp. About 1000 people from 4 villages combined to put on for us a

show of martial strength and tribal tradition, including about 100 war canoes, mostly manned

by 5 men each. Meanwhile and afterward, on shore, women danced for us. After the show,

we were free to roam the village and to see (e. g.) the "man house" where men gather to meditate

and to discuss. We were allowed to see a bit of their life style, although I entered no individual

house. And we could see and if interested buy some of the elaborate wood carvings for which

these people are famous. Having too much stuff already, I only looked and took pictures.

Before I include some of these, here is more information on the Asmat:

Paraphrasing Wikipedia: "The Asmat are an ethnic group of New Guinea, residing in the

province of South Papua, Indonesia. They live in a region on the island's southwestern coast

bordering the Arafura Sea, with lands totaling ~ 7336 square miles and consisting of mangroves,

tidal swamp, freshwater swamp, and lowland rainforest. The land of Asmat is located in and adjacent

to Lorentz National Park, the largest protected area in the Asia-Pacific region. The total Asmat

population is ~ 110,000 as of 2020. The Asmat have one of the most well-known woodcarving traditions

in the Pacific, and their art is sought by collectors worldwide.

The natural environment is the major factor that affects the Asmat: their culture and way of life

depend on the natural resources found in their forests, rivers, and seas. Their food consists mainly of

the sago palm (Metroxylon sagu) supplemented by beetles, crustaceans, fish, and forest game. Due to

frequent flooding, Asmat houses are built two or more meters above the ground on wooden posts.

The Asmat traditionally emphasize the veneration of ancestors, particularly those who were

accomplished warriors. Asmat shields are among their most famous products. Asmat art consists of

elaborate stylized wood carvings such as the bisj pole and is designed to honour ancestors. Many Asmat

artifacts have been collected by the world's museums.

The Asmat have traditionally been known for their warrior prowess and headhunting raids.

Every death of an adult was believed to be caused by an enemy, and relatives sought to take a head

in an endless cycle of revenge and propitiation of ancestors. Heads were part of the rituals by which

boys were initiated into manhood. Cannibalism was a feature of these rituals. All this is believed

to have been suppressed by missionaries.

In this context, there is a famous story of Michael Clark Rockefeller (born May 18, 1938),

who disappeared in 1961 while exploring this region. Again, paraphrasing Wikipedia: "He was a son of

New York Governor and later U. S. Vice President Nelson Rockefeller, a grandson of American financier

John D. Rockefeller Jr., and a great-grandson of Standard Oil co-founder John D. Rockefeller Sr.

On November 17, 1961, Rockefeller and his companions and local guides were in a 40-foot dugout canoe

about 3 miles from shore when their double pontoon boat was swamped and overturned. Their local guides

tried to swim for help. On November 19, Rockefeller tried to swim to shore and disappeared. No remains

of Rockefeller or physical proof of his death have been discovered, despite detailed investigation.

He may have drowned. He may have been killed by marine life. Or he may have been killed by the Asmat

in retaliation for killings by the local government." The myth persists that he was eaten by the Asmat,

and claims to that effect have been credited to some Asmat. Repression of the kill-for-a-kill culture

had been ongoing for years, and it is reasonable to expect that this was more successful near the coast

and in places where contact with non-Asmat culture was most common and that it may not have been

successful in places that were (and still are) more isolated. I include the myth because it is so

thoroughly a part of the story of the Asmat people. However:

I emphasize: Although the body decoration and ritual performances that we saw were impressively

martial, we were treated with consummate respect and kindness. This was especially relevant as we

struggled with the deep mud that surrounds the village. The atmosphere was wholly friendly, and

there was not the slightest hint of danger. What there was -- in abundance -- was respect for

tradition, and every effort was made to show us that tradition.

Continuing to paraphrase Wikipedia: "Even today, the Asmat are relatively isolated and

their cultural traditions are strong. Still, many Asmat have received higher education in other

parts of Indonesia in Europe. The Asmat find ways to incorporate new technology and beneficial

services such as health, communications, and education, while preserving their cultural traditions.

The biodiversity in this area has been under pressure from outside logging and fishing,

although this faces significant resistance. In 2000, the Asmat formed Lembaga Musyawarah Adat Asmat

(LMAA), an organization that represents and articulates their interests and aspirations. In 2004,

the Asmat region became a separate governmental administrative unit or Kabupaten, and elected

Mr. Yufen Biakai, Chairman of LMAA, as its Bupati (head of local government). In 2022, following

the formation of South Papua province which includes Asmat Regency, Apolo Safanpo, a native Asmat,

was appointed as the first governor of South Papua."

With this context, pictures follow:

This was the longest and most cumbersome zodiac excursion of the trip. Part of the reason

was that the expedition crew decided to use all zodiacs in convoy, and to not start the run to

Uwus until all zodiacs were loaded. Since our Photo Masters zodiac was loaded first and sailed

first after the lead, scout boat, we had to wait a long time at the ship while all the rest of the

zodics were loaded. In glowering weather and intermittent light rain, we had to sail about 6 miles

from Seabourn Pursuit to shore and then a similar distance upriver to Uwus. Part of the reason to

convoy was that, as we approached the village, more than 100 war canoes started to pass us,

beginning a loud, complicated, and well choreographed martial display:

This is the first war canoe that I photographed.

More war canoes passed, with warriors shouting and banging oars against their canoes in shows of ferocity.

Warrior decorations became ever more elaborate ...

But apparent strength of character does not require elaborate decoration.

After some confusion during which canoes and zodiacs mixed freely ... but with no personal

interaction between Asmat people and people in canoes ... the canoes started to line up in

formation between us and the village.

So with a lot of not-at-all obvious but clearly choreographed maneuvering, we ended up with the

zodiacs on the side of the river opposite to the village, facing groups of warriors in canoes ...

... and facing groups of mostly women in the village at river's edge. Scroll right to see this

complete panorama.

The warriors in the canoes then gave us a complicated show of martial strength, accompanied by

shouting and banging of oars against the canoes, as in this

movie.

Meanwhile, women, children, and older men waited on shore.

And we, too, got ourselves onshore ... with a lot of scrambling to cope with deep mud.

Women and children also danced for us, as in this movie.

I emphasize: Casual nudity and even -- among the men -- occasional nudity to emphasize prowess --

was common and had no lascivious intent. It would waste a lot of the emphasis of the cultural

traditions on display to us if I had edited out all such nudity. No inappropriate connotation

should be ascribed to any level of nudity that the Asmat displayed.

At this point, there was a break in our zodiac landings as the war canoes came in to land.

The great effort that the Asmat put into showing us their cultural traditions and the

complication of all these ceremonies is nowhere better demonstrated than in

this movie of the canoe landings.

Whatever we might have been told about our destination today ... "Kampung" means "village" in

Indonesian, so I assume that this place was Bou Village. We were told that at least 4 villages

of people joined up in putting on today's show of Asmat culture.

At this point, all organization evaporated and we were free to wander the village. This is one

of the raised walkways that led from the river shore into the heart of the village.

Village scene -- At this point, the weather got much friendlier ... which also means that it got hot.

This is the eastern, upriver edge of the village. Beyond lies jungle.

Another village scene

Some of the raised walkways were a bit ... adventurous.

This one was a little too adventurous for my taste. Normally, I'd manage the balancing act,

but I was too hot and too tired to risk the consequences of screwing up. So I "chickened out".

At about this time, I started to look for the way back to the zodiacs. But I had not seen the

"men's house" -- in the chaos on shore, nobody pointed it out. Luckily, I found it by accident:

Men's house of the Agats

We -- including women -- were freely allowed in the Asmat men's house. Here and along the

raised walkways, their remarkable woodcarvings were on display and on sale. The atmosphere

toward us was unfailingly friendly.

After visiting the men's house, I got into a long line in deep and slippery mud to get onto

a zodiac for the long ride back to the ship. This will almost certainly remain the most

memorable day of the trip.

I have wanted for many years to visit the fabled islands of Raja Ampat. The name means "Four Kings"

in Indonesian, referring to the islands of Misool (where we went on Sept. 10),

Salawati,

Batanta, and

Waigeo (where I went on Sept. 11).

Wikipedia gives more detail.

Raja Ampat's beauty is most obvious in an aerial photo such as the above (credit:

Jeremy Bishop on Unsplash, curated by Simon Spring).

Map of Raja Ampat

in the context of our trip.

To put the area in context, I include the above map with areas identified that were visited by

the cruise (e. g., Darwin to Broome, Agats to Raja Ampat to Cenderawasih Bay and on to Papua

New Guinea) as well as Singapore, which we visited before the cruise. Also marked is Waisai on

the island of Waigeo, which I visited in the minimally successful attempt to see Wilson's

Bird of Paradise on September 11.

We spent September 9 and 10 visiting two island groups in Raja Ampat via Photo Masters zodiac rides,

documented here.

Day 1 = September 9 started out spectacularly and stayed wonderful all day.

This panorama (scroll right to see it all) begins to give the feel of many karst islands,

each topped with forest.

Once we were out on our zodiac cruise, we were treated to an ever-changing kaleidoscope of

wonderful karst scenery.

The weathered and lichen-overgrown karst walls of the hills often was magically artful, much

like the erosion on the walls of the King George River gorge was 3-D art. In addition, an

early target of our cruise was ancient handprints outlined in red pigment, safely placed on

protective overhangs. We were told little about the artists, but a web search provides

this paraphrased comment: Rock art is part of the Austronesian Painting Tradition, a form of

visual expression that probably began ~ 4000 years ago with the spread of Austronesian speakers.

It is interesting to view this -- like some (not all!) similar Aboriginal art in Australia --

as a manifestation of the very human impulse to leave behind concrete signs that "I was here!"

There are similarities in these handprints with carvings of "Kilroy was here" in some western-culture

tree trunk or, indeed, in graffiti on walls of modern US and European cities. When it may be

4000 years old, it is regarded as art. When it is well enough executed, it can be regarded as

modern-day art in graffiti form, too ... or else, it is just a nuisance that damages the

beauty of some Renaissance building in Europe or some cleancut (if not artistic) subway wall

in New York City. People don't change much. But early development of the homo sapiens

impulse to record abstract ideas (even "I was here") in pictures that were hoped to last for

a long time -- that development is of great interest in the context of our understanding of how

civilization developed.

And, of course, the next step of recording the history of battle (versus nature or versus other

humans) and the still more abstract idea of embodying strength or wisdom in pictures, including

religious art, speaks more profoundly to our understanding of the development of intelligence.

So handprints as rock art are important parts of the history of the development of human culture.

Rock art detail

It is not clear whether the figure to the right of center depicts a human, and animal, an insect ...

or an extraterrestrial alien! But it looks more abstract than "I was here." If it is human, then

it does not have correct proportions. On the other hand ... it could be interpreted

as a (not-well-shaped) human who is being attacked by a crocodile. Or maybe I am 100 % wrong.

We will never know.

Overhang with rock art. Note the peculiar formation at bottom left, shown below:

Peculiar hanging formations that look a little like boot-shaped "stalagtites".

Brahminy kite

Karst islands with trees thriving in the most unlikely-looking ledges

Here, too, effects such as erosion and lichen produce a distinctive sort of -- perhaps macabre -- art.

Walls and zodiacs for scale

Wall art with more abstractions but also with more erosion, hence hard to interpret

Raja Ampat islands with Zodiac and Seabourn Pursuit

Island undercut by waves in a roughly 6-foot tidal range

Islands wonderfully characteristic of Raja Ampat (scroll right to see this panorama)

Varied landscape of karst walls, tiny sand beaches, and forest-covered islands -- remnants of what

must once have been a rugged mountain chain

Today's last closeup look at the islands of Raja Ampat

Sunset on a very satisfying day, from the balcony of our Suite 800 on Seabourn Pursuit

Still in the heart of Raja Ampat, we had another spectacular (if rainy) zodiac cruise. This picture

from our suite's balcony shows part of the island chain extending ESE from Misool that we explored

today. It is already raining, so you see signs of how it will go: We had cloudy but good enough

weather early on, and then it started to rain harder during the last 1/2 hour out. This was a

Photo Masters zodiac cruise, so the good news is that we explored in satisfying depth ... and the

slightly less good news is that participants were willing to endure quite a lot of rain before we quit.

Still, it was an eminently satisfying day: The weather could have treated us a lot worse (see my

account of September 12) than it did. Scroll right to see this 180-degree panorama.

Islands in the chain, still as seen from our balcony: The mist and rain provide some sense of depth

to this image.

Islands of the Raja Ampat archipelago, with zodiac for scale

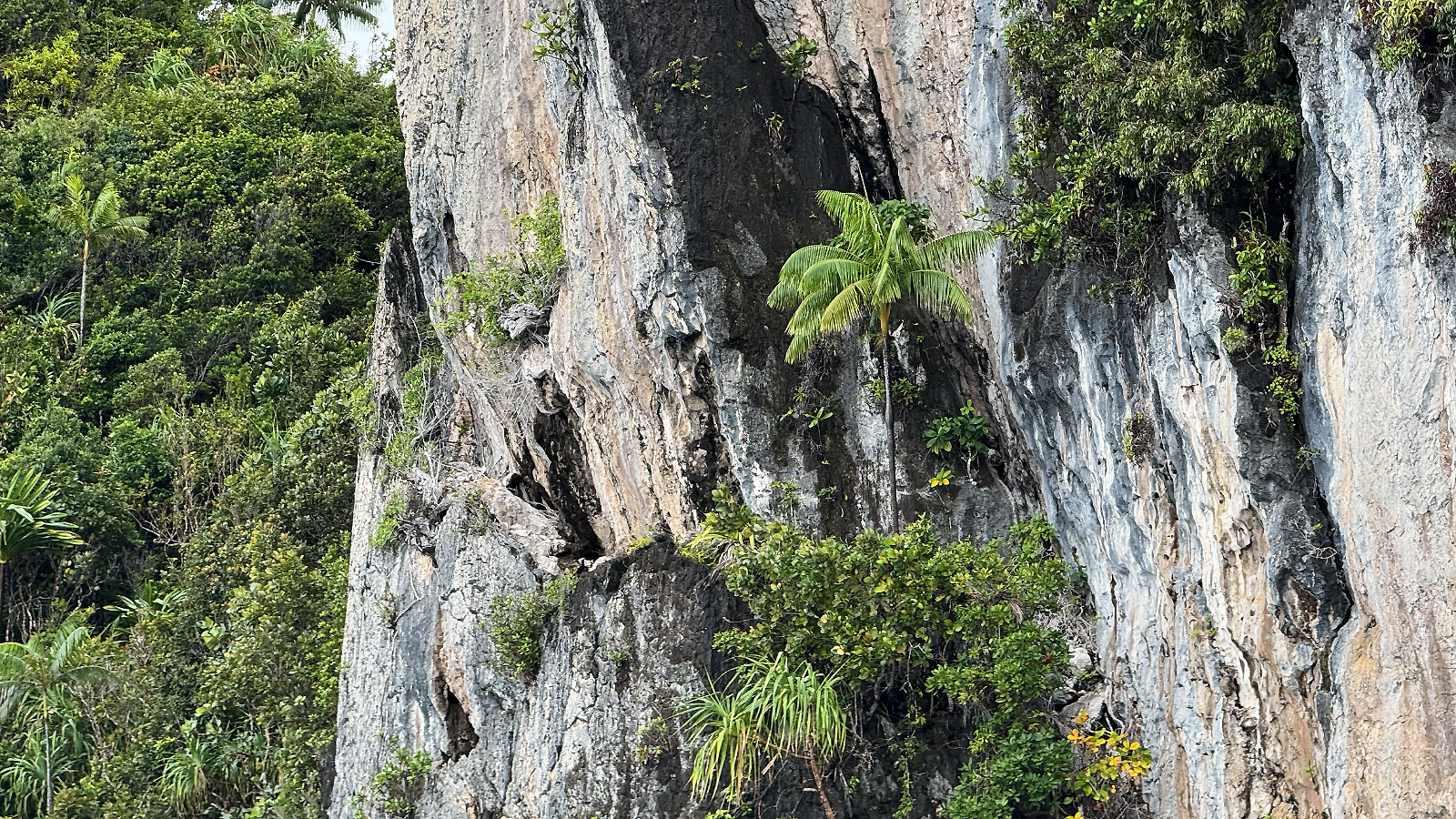

These islands are clearly the remnant of a rugged mountain chain: It is interesting how many

vertical cliffs there are even after so much erosion. And it is starkly clear that A LOT of

erosion has occurred, as is most dramatically shown by the otherwise subtle observation that the

water is rarely deep between islands (see, e. g., the aerial picture at the start of yesterday's

account). Mountains don't form in nearly vertical summits above flat plains. No, they form rugged

peaks with deep, jagged valleys between them, as in the Himalayas. Here, the deep valleys have been

filled in by erosion. But here, erosion nevertheless leaves behind many vertical walls. (Contrast old

mountain ranges such as the Appalachians in the USA, in which mainly rounded mountains are separated

by gentle valleys.) Another reason to expect massive erosion here is that much of the rock is limestone,

which dissolves easily in only mildly acidic rain. Evidence for that kind of erosion -- which creates

multiply connected cave systems -- comes below in the next pictures from today. And of course, meanwhile,

we are in the wet tropics, so even the tiniest amount of soil that is produced and left behind by

erosion gets covered with forest, except on the most vertical -- and plausibly: the most recently

exposed -- walls.

I was not sure of it at the time, but this looks like part of a cave that has been opened to the

outside world via erosion of overlying rock. It already looks dramatic ... but check out the

more convincing pictures that follow:

These flowstone features must have been laid down over thousands of years, deep inside a cave

in a mountain that is ..... gone. It is open now to the elements, and starting to be overgrown

with vegetation. The karst mountain tips that we saw all around us -- essentially all covered

now with forest -- are largely made of limestone and must be riddled with caves. We saw only

a few hints, like this one.

Vertical panorama from underwater coral through the flowstone features to the upper part of

what remain of the mountain

On the dramatic cliffs, even the tiniest amount of soil that's produced by erosion and fed by

early growth gets used by trees.

Trees eking out an existence on what here looks like lava

More of the endless array of islands. It is instructive to notice how they are undercut by the

sea. These cuts are consistent with the typical tidal range of ~ 6 feet. But we never saw similar

cuts at higher levels on the hills. So ocean levels have never been much higher than they are now,

at least not in the lifetime of island features as we see then, which can be tens of thousands of

years. Of course, there could be and probably are such cuts tens and even hundreds of feet under

water, given that ocean levels were much lower during Earth's glacial maxima.

You get the best feeling for the Raja Ampat experience from movies such as

this one (even if the zodiac driver is in a hurry

to have you sit down so he can start moving)

and

this one

and

this one.

We were captivated by dramatic headlands ... and the seemingly endless variety of islets.

Meanwhile, the swirling weather is bringing rain closer and closer.

This is an interesting headland -- the only one I saw that appears to have, cut into it, the sort

of shelf that is cut under an island via erosion by sea waves. If that's what this really is, then

it is evidence that the cut was once at water level. And if all that is true, then I suspect that

we see evidence of uplifting rather than evidence that ocean levels were once different. Trouble is:

there were no other features nearby that might give further evidence about the cause of what we see here.

It is possible that there was just an unusually fragile rock layer along the line that is now cut away.

What remains clear -- and in no sense surprising -- is that this area has a long and complicated

history.

Raja Ampat certainly lived up to its promise of beauty and drama.

And you continue to get a feel for the 3-D geography -- e. g., for the different distances to different

islands -- from this movie. Note that by now, it is raining.

By the time I got back to the ship, I was pretty well soaked. But happy!

Today was a complicated failure:

I worked for months to arrange a private excursion to see Wilson's Bird

of Paradise (my "most wanted bird"), Red Bird of Paradise, and hopefully other new species in

the (for birding) virgin territory of West Papua. The ship scheduled a landing at Gam Island,

starting with an 04:30 hike to get Red Bird of Paradise. That hike sounded intimidatingly difficult,

and its success record was not great. In the afternoon, the ship was scheduled to have a landing

at Mansuar Island, south of Waigeo. I knew that Wilson's Bird of Paradise could be seen on Waigeo,

and I was put in contact with an excellent bird guide to help me to get it. I do not mention his

name here -- he honorably did his best, and I do not want his name to be associated with a failed

day. Anyway, I arranged to be picked up at the village of Sawinggrai, taken by speedboat in ~ 45

minutes to Waisai on Waigeo, taken to a hide for Wilson's and later to a different hide for Red

Bird of Paradise, and then delivered, again in a ~ 45 minute speedboat ride, to Swandarek village,

where Seabourn was by then to have arrived. This required Seabourn to sail from Gam to Mansuar with

a passenger missing. That's not allowed. I had get special permission to carry out my plan. It

was duly (if not entirely cheerfully) granted.

In the event, this complicated choreography went fine. The speedboat rides were unpleasantly

rough. The > 1 mile hike to the Wilson's hide was not easy, although it was not intrinsically

hard -- 2/3 level and then 1/3 gently rising, but in very warm, very humid weather. We got to the

the hide just before 7 AM, when BoP displays were expected to start. The guide and his assistants

were wonderfully helpful with my difficulties with the trail and especially by carrying my gear.

And that's the end of the good news. We waited > 3 hours, until the day got too hot for bird activity.

Wilson's Bird of Paradise sang repeatedly from high above the hide. It hissed its threat call.

But it came ........ for perhaps 0.2 seconds, landing ~ 25 feet away from me. I got only a fast,

indirect look which showed roughly this:

This is the ebird picture of Wilson's Bird of Paradise, reduced in size to roughly what I saw for

much less than 1 second and only with the naked eye. The red and blue patches were striking. I

did not see the curled tail. For sure, I got no picture. The bird immediately flew into a tree

for a few seconds and then flew away.

It did not return. In fact, I saw exactly zero other birds during the whole excursion. No other

birds came to the hide. We got no birds -- new or otherwise -- during the hike back. Which

was unspeakably hot. So, other than the 0.2-second look, the day was a failure.

One thing that I did not like: Neither the hide owners nor my guides were willing to look for

the bird in the trees. I could perhaps have gotten a takable look.

But they are so used to depending on the success of the hide that they refused to try anything

else. So the whole complicated excursion was a frustrating waste. I fear that there was

too much commotion in the hide, with (as it turns out) 2 birders and at least 4 helpers.

Or maybe this was just a day when the bird was uninclined to appear. That happens.

Ironically, some people who took the Seabourn hike saw Red Bird of Paradise very well.

Pulau ("Island") Matas is an island in Cenderawasih Bay, the tiny tip of an atoll that

measures about 1 x 1.5 miles. The island is about 100 feet wide and less than a mile long --

a thin strip of sand with a few trees. We were scheduled in the AM to land there for a

beach swim and snorkel. This was to be my first snorkel in about a decade. It was also

my first snorkel with new diving gear bought for this trip way back when I still thought that

it would offer scuba diving, including a shorty wet suit, prescription goggles, diving boots

and fins, and underwater camera. As a snorkeling trial, it was successful. As a snorkeling

experience, it was not:

Pulau Matas beach, in the first official picture taken with my new OM System TG-7 underwater

camera. The narrowness of the island is clear. So is the threat of heavy rain coming in

from the left. The people in the distance are snorkeling; those on shore include Seabourn's

snorkeling managers.

It was already raining during my zodiac ride to the island. During the ~ 1/4 mile walk to

the snorkel site, above, the rain got harder. As I struggled -- more or less succesfully --

to get used to my new equipment, the rain turned torrential. I as just getting comfortable

enough to go to look for coral when I got a tap on the shoulder: "We are aborting the snorkel."

Which required an unpleasant walk back to the shivering crowd that was waiting for zodiacs

back to the ship. And a cold wait, partly under an awning and partly in the rain. I am glad

that I wore a wet suit! I "got away with" the experience without catching a bad cold.

I skipped the PM landing at Yende village -- a social occasion: not my forte.

Their welcome is shown above, as seen from our balcony.

Vanimo is on the north shore of Papua New Guinea, so there was, in principle, good potential

for new birds. Also, today was the 50th anniversary of the independence of PNG. So our ship's

crew decided that we would not land at Vanimo, a substantial and probably raucous port city.

Instead, we would land across the bay from Vanimo and visit Vanimo Surf Lodge. This sounded

like good news: perhaps a walk along the forested beach might yield new birds. Didn't happen.

The beach was idyllic and inviting. But you have to decide whether to swim or to take a camera.

It is not safe to do both. I brought my camera and tried to walk along the beach's forested edge

to see birds. I heard a few chirps but got only 2-second views of 2 flying birds -- not photographable.

The problem proved to be exactly what I feared,

(1) birds near town have mostly been eaten or gone far inland, and

(2) local people -- probably well intentioned, but you can never be sure -- kept following me.

I had to give up and go back to the ship, having seen nothing.

It's too bad: The forest was inviting, and serious birding with a good guide would be productive

in this part of PNG. But that's not something that Seabourn would arrange.

Today, we were scheduled to have our first submarine dive, to about 100-150 m depth off the

outer slopes of Garove Island, Papua New Guinea. Waves were too choppy by the time we got

to the dive site, and the dive was aborted. But not before Mary got seriously seasick.

Which is remarkable, considering that she never got seasick even with 25-foot waves in

Antartic and Arctic waters.

This Google Maps aerial picture shows how Garove Island -- in the middle of the concave-northward

crescent of West New Britain, itself volcanic in origin -- is the caldera of a volcano. The ship

was taken into the caldera for a landing at a local village. There was even some birding scheduled.

But we were scheduled for a submarine dive on the outer slopes of the volcano, at roughly the place

shown in the above photo. According to the people who made the dive before us, this turned out to

be a disappointing sand and silt slope to a plain mud bottom, with not much to see.

Entrance to the caldera as seen from Seabourn Pursuit in the morning. The weather was slightly

blustery ... and got worse as our 11:30 AM dive departure approached. In the event, the zodiac

ride was rough enough so that Mary got seriously seasick. And, when we approaced the sub, bobbing

on the surface, it turned out that several people on it also got seasick. The dive was aborted and

we all headed back to the ship together. On an expedition cruise, such events have to be expected.

This morning featured a strenuous drift snorkel at Duke of York Island. I prudently skipped it.

The ship then moved to Rabaul, the capital of PNG's West New Britain island and province until

1994, when an eruption of the volcanoes Tarvurvur and Vulcan destroyed enough of the city so that

a new capital, Kokopo, was build 20 km away. Rabaul remains an active port city, even though

its outer bay is the caldera of Vulcan. We have been (more or less) here as part of our

Victor Emanuel Nature Tours birding

tour of PNG. We did not tour the city then, and we didn't tour it now, except for the important

ceremony of the fire dance, below.

Mt. Tavurvur erupted again in 2014. We were here in 2022.

Mt. Tavurvur from the balcony of our suite on Seabourn Pursuit, while we were docked at Rabaul on Sept. 19.

Note: the smoke has nothing to do with the volcano.

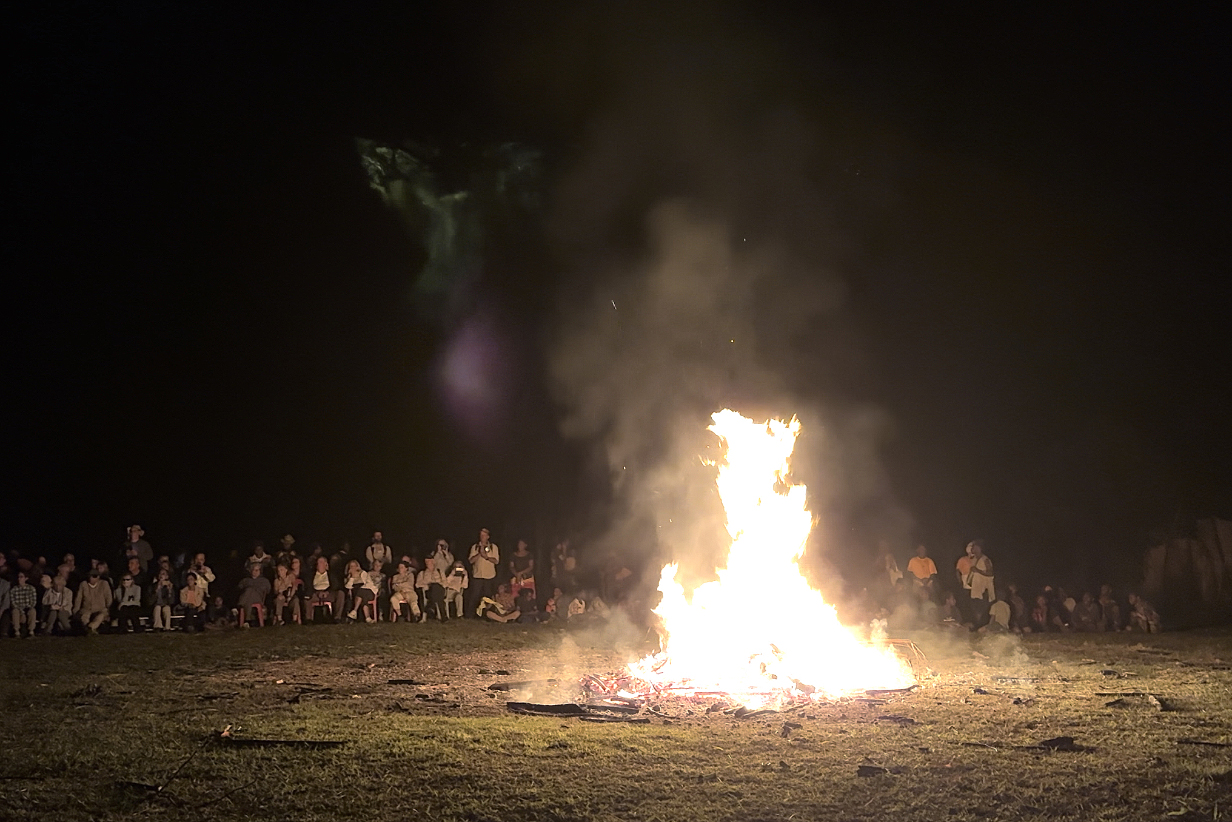

In the evening, most people on the ship were taken ~ 1 hour from Rabaul into the mountains to the south

to see the famous fire dance of the Baining people. A description and explanation is posted on youtube

here. However, we are told that much of the

meaning and importance of the dance are secrets shared by only a few men among the Baining. The aspect

of the dance that was most obvious to us is that young men from the village are dressed to represent

spirits who dance in part to appease the volcanoes Tarvurvur and Vulcan. In doing so, they supposedly

become those spirits and hence withstand the flames of the bonfire. We watched the dance for about

an hour, but it typically lasts all night, "fueled" in part by the stimulant of betel nuts.

I photographed it and made videos only with my iphone. I am just getting used to it, and the quality

is not superb. But the experience was every bit as impressive and unique as promised.

Note: Since my attempts to edit movies result in loss of quality, I post the movies as taken,

even when there are distracting bits that would better be edited away.

Before I start, a personal quirk:

At times in the movies that follow, ghost images of the bonfire look like phantom spirits at play

within the story, as in this movie. Here, the spirit

hovers back and forth over the fire. In the following movies, I sometimes try to make these "spirits"

be part of the story. No disrespect to the Baining ceremony is implied.

The dance gets started. Eventually, with breaks for other figures to appear, at least 16 spirits

like this one had appeared, dancing between us and the fire and then gathering to its right, as seen

from where we sat. This one is called an "anguangi" and represents an animal.

This figure -- one of several "avriski" -- appeared next and,

danced his way to the first spirit,

now at right.

Soon there were 8 spirits around the fire ... with more on the way.

By the time of this movie, more than a dozen

volcano spirits had appeared.

As the dance progressed, spirits flirted closer and closer to the fire.

Now, in this longest (10 min 23 sec = 3.76 Gb) movie,

near the middle, the dance gets more free-form, as all the dancers start to circle the fire. Some,

like the two in the above pictures from near the end, get intimate enough with the fire to kick it.

This movie best captures the feel of the fire dance. (Although I should have known better than to

zoom in to 5 X near the beginning.)

Scenes from the melee

Late in this movie, spirit warriors begin to dare to

jump right onto the fire. Meanwhile, I get the impression that the drummers are getting tired:

they are not always in synch, as they were early in the dance.

Eventually ... even though the dance probably went on ... we and

the figurative fire ghost departed, , in our case,

back to the ship for a late supper.

It was a spectacular performance.

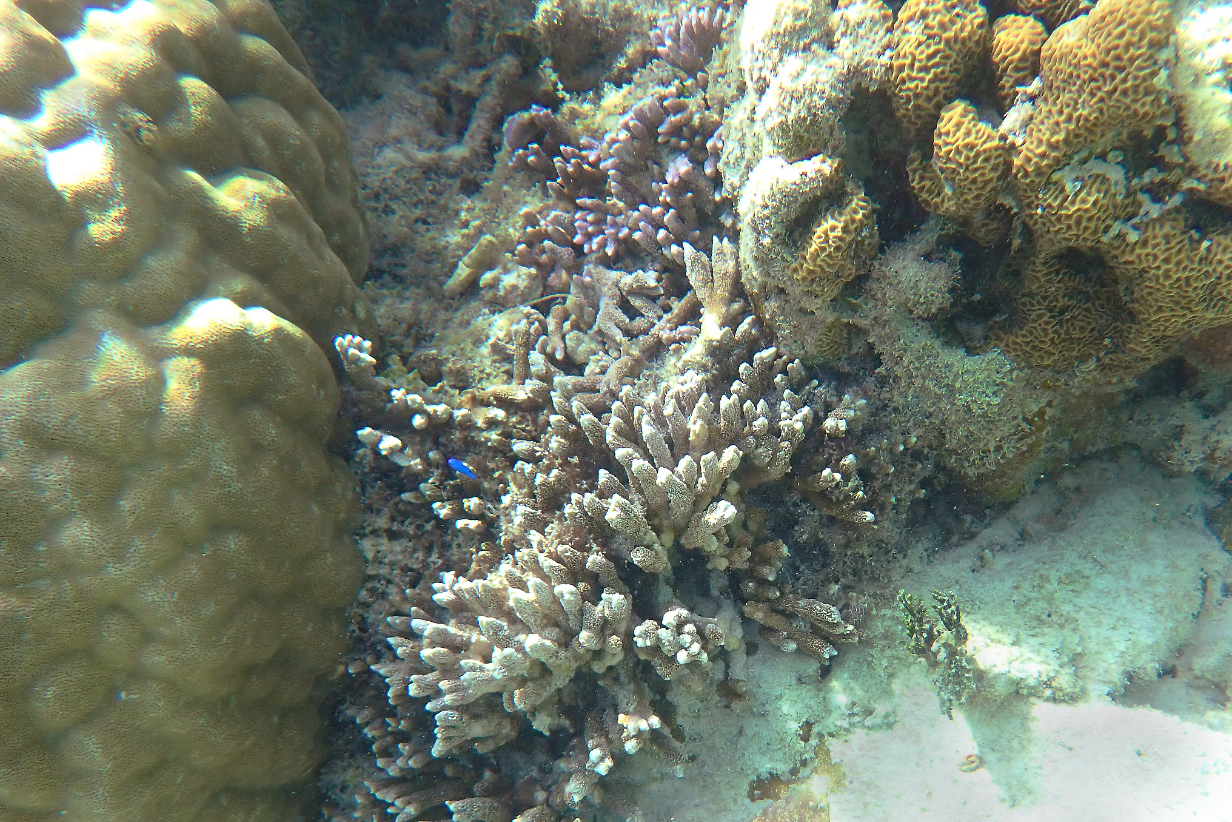

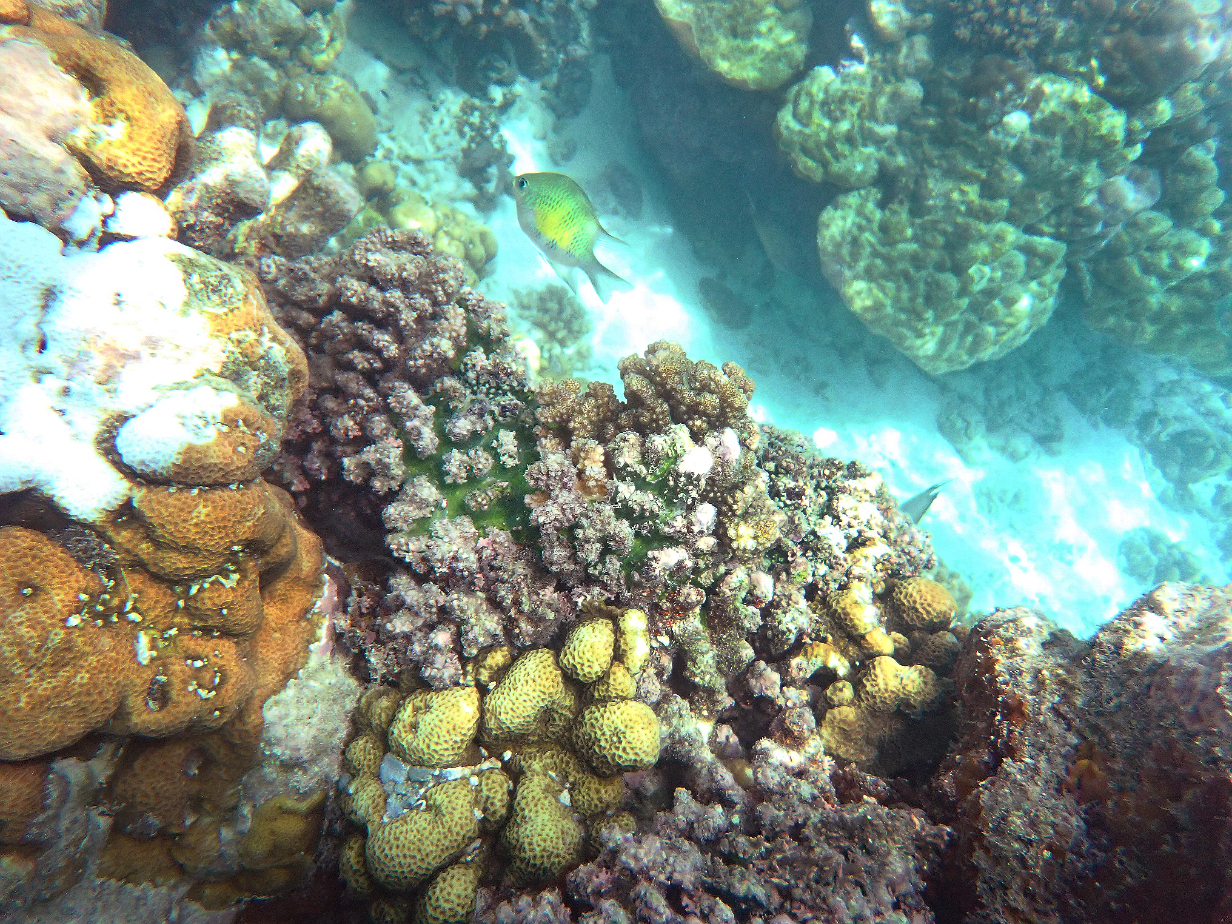

Today, we arrived at the Solomon Islands, which are John's 56th country visited. The tour

itinerary said that we'd be at Ghizo Island, but in fact we went to tiny (500 m long)

Njari Island to snorkel and have a beach day. This was my first chance to really try out

my new snorkel gear, including my underwater camera. I was noticeably clumsy, having not

snorkeled in several decades, but settled in reasonably well after 1/2 hour of practice.

The camera was new to me, and I did not know its controls at all well. Ship's photographer

Harry Asland set it up for me, and it worked fairly well. It tended to overexpose pictures;

I still need to solve that. I never snorkeled into significantly deep waters, so the coral

and fish that I saw are not the best. Still, here's what I got, in chronological order:

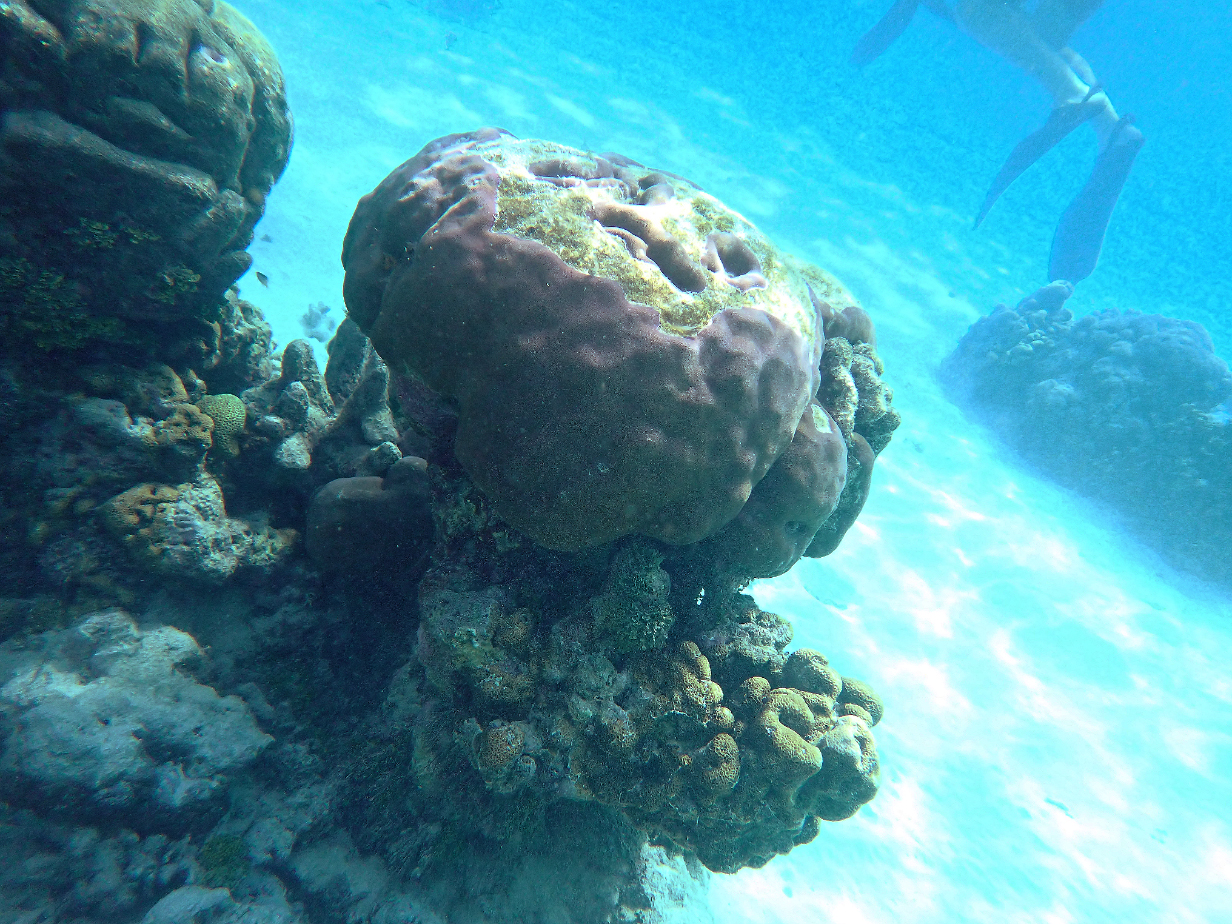

My first underwater picture that is (barely) worth keeping

This is a tiny giant clam, about 6 inches long. It quivered its shell open and closed as I watched.

The dark blue spot at the bottom of the frame is shown in the next picture:

This is a still younger giant clam -- barely 2 inches long and only a few inches away

from its (still tiny but bigger) neighbor, above.

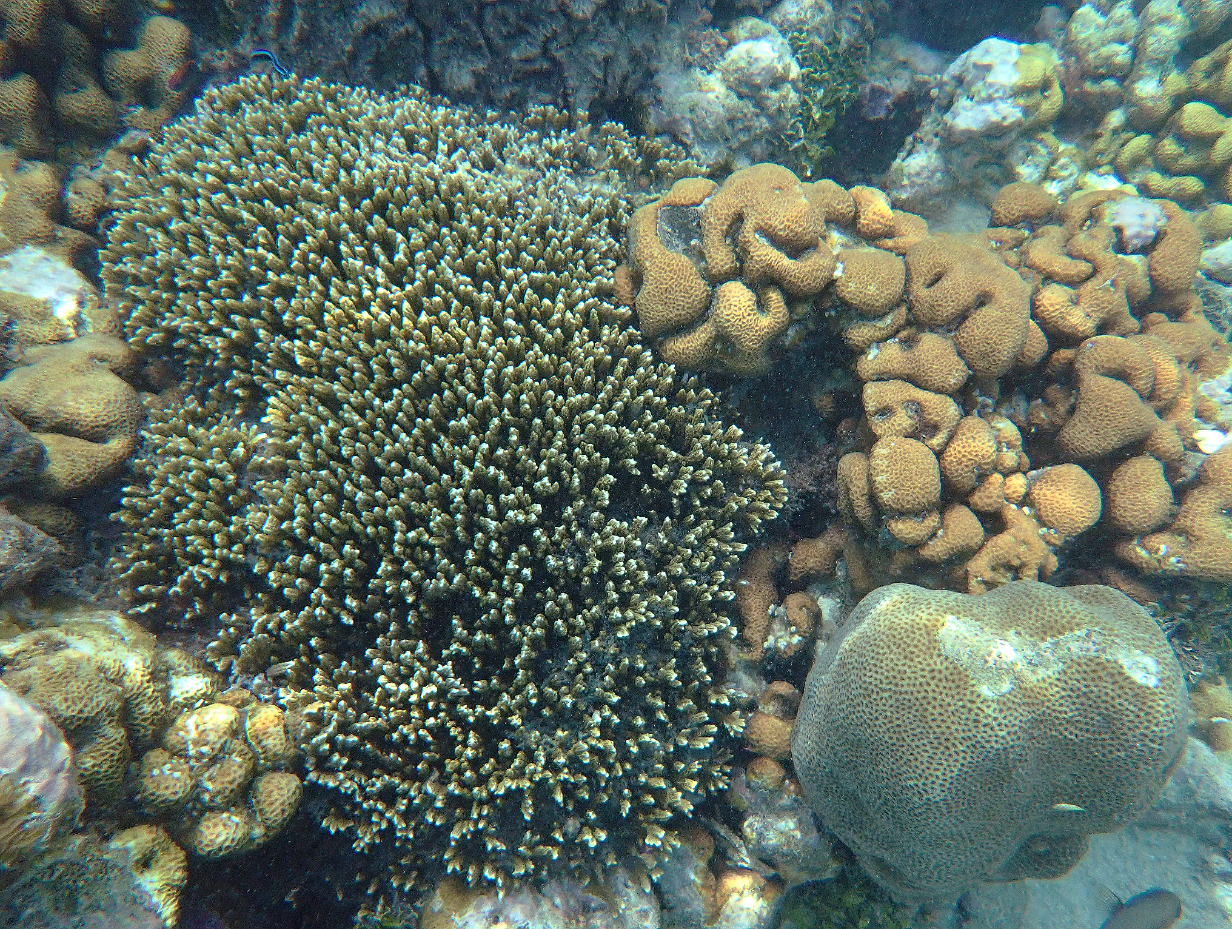

The coral was patchy and not very healthy so close to shore.

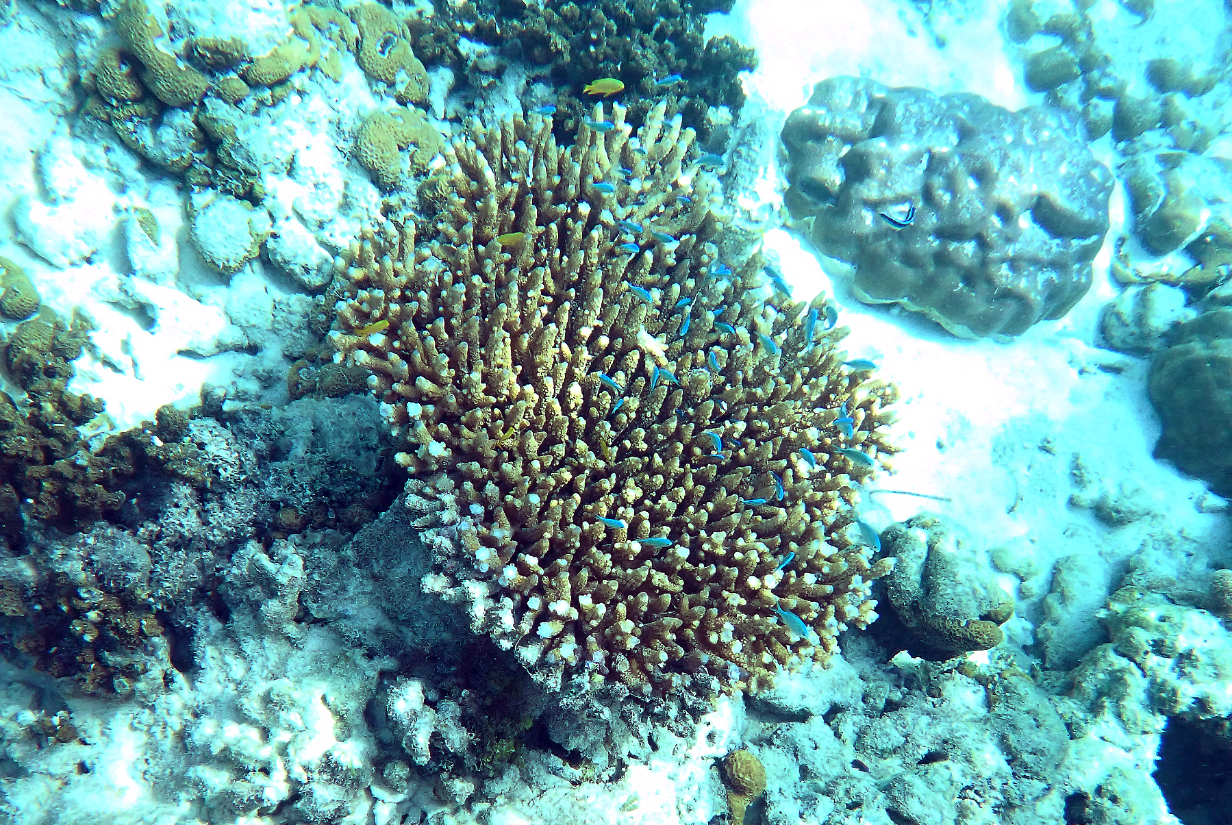

Most of the fish that I saw were electric blue and tiny ... cleaner fish?

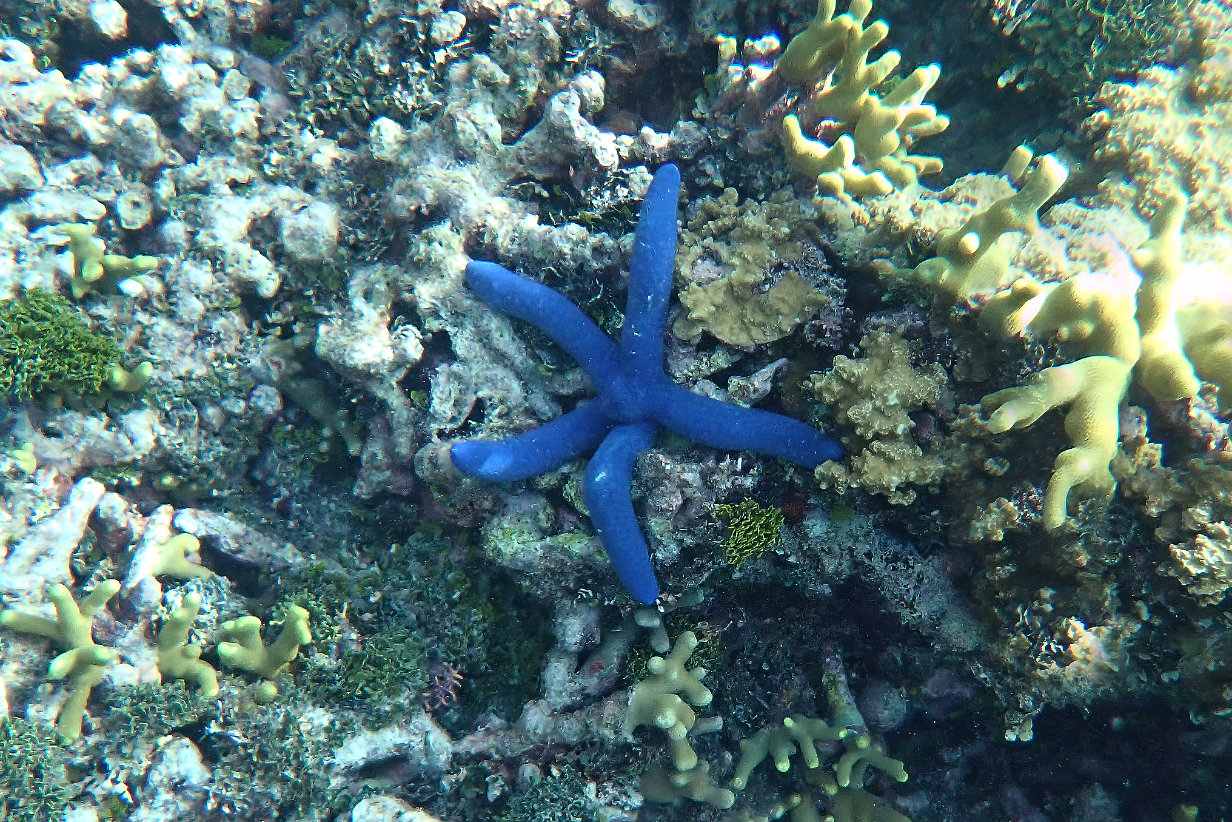

Blue starfish

I don't know these waters -- I don't even know the names of the fish and corals that I saw.

Snorkeling here is a very new experience for me.

Corals were healthier farther from shore. I think that the tiny striped fish at top-left is a cleaner.

Hiding ...

Remarkable little school of bright blue fish. Again, I wonder if these are cleaners ... or just

juveniles that use the reef as a "nursery".

On this first serious snorkel in decades, I did not go very far out or see very remarkable reef life.

But I got somewhat more comfortable with my new snorkeling and diving gear. I hope to do better

next time, if I can better understand how to use my OM System GT-7 camera. It works fine but is

complicated, as all serious cameras are, nowadays. I have a lot to learn to optimize it for whatever

conditions I encounter. Still: today was in essence a success. And the venue -- a sand and palm tree

haven in the tropical Pacific -- was a delight.

Today, we docked at Honiara on Guadalcanal at ~ 8 AM and stayed until 6 PM, so it was possible to

get ashore easily and bird this very substantial island in more detail than has been possible at most

landings. I had arranged a private birding tour with the shore excursions group of Vacations to Go

(cedwards@vacationstogo.com, kallen@travelps.com). My overall tour guide was Bernard Rizu

(bernard.rizu@gmail.com) and my driver was Starling Andrew. Samson Hoasi was my bird guide on

Maunt Austen. We spent most of our time and had the best success there. All three gentlemen worked

hard to be helpful. Birding was somewhat hampered by the late hour -- we got to Mt. Austen only at

~ 9 AM, when it was already getting hot -- and by housing development reaching up to our high point

on the road. But from that high point on down the mountain away from Honiara, the forest was

still pristine and productive. I managed to get 7 life birds. Not bad, for a hot day.

Here as in so many places (e. g., Hawaii and Australia), Common myna are taking over in the city.

I saw this bird while waiting at the dock for my guides.

I spotted my first life bird almost immediately on Mt. Austen, and it was glorious --

Yellow-bibbed Lory.

Solomons corella (This is my life bird.)

Claret-breasted fruit dove (This is my life bird. It is not ideal when the defining feature of

the bird shows barely a hint. It was also -- as almost all life birds were, today -- far away.)

Sacred kingfisher (This bird was instantly "called" Ultramarine, which would have been new.

But it is obviously the ubiquitous Sacred kingfisher.)

Buff-headed coucal (This is my life bird. The red eye is obvious in the original image.)

Red-knobbed imperial pigeon (We had seen it

in West New Britain, but never this well.)

The next life bird was Woodford's rail, well seen in the road at the summit. But it hid in tall

grass before I could get a picture.

Blyth's hornbill (Gigantic bird, far away: It's a good thing that we have seen it better along

the Fly River in Papua New Guinea -- see link above.)

Pied goshawk (This is my life bird, spectacularly close!)

Long-tailed mynas ... very far away, but cute

Brown-winged starling (I missed it earlier on Mt. Austen but got it at the Honiara Botanical

Garden. This is not a flattering picture ... but it is my life bird, the 7th and last of the day.)

The crew of thre ship decided not to land us at Vanikoro Island as listed in the voyage itinerary

but instead to take is to a small island -- Nanunga Island -- off the north coast of Vanikoro.

They originally claimed that no cruise ship had ever visited here. That turned out not to be true.

The island has a style liked by the crew -- 1/2 km long with sand beaches, some snorkeling possibilities,

some forest cover, and local people who would welcome us with a formal ceremony. Also listed was

the possibility of a "nature walk" or (possibly) a bird walk, led by our birding expert JJ Apestegui.

I went for the bird walk ... which turned out to be only a nature walk. JJ did mention, though,

that he had seen Cardinal myzomela, which would be new for me. At the end of the walk, he told

me where he saw the birds. I spent 1-2 hours there looking, even though I was by this time tired.

JJ joined me to help, for which I am grateful. In the end, several adults flew by too quickly for

me to see them. And then, a juvenile perched long enough for pictures.

Nanunga Island from Seabourn Pursuit with Vanikoro in the distance. I got Cardinal myzomela

from the beach that you see here, roughly in the middle of the island.

This was the idyllic setting where I got the bird ... with Seabourn Pursuit in the distance.

Cardinal myzomela juvenile, with already red back but, so far, only reddish throat and otherwise

still black. This is my life bird.

Seabourn Pursuit's stop today was at the island country of Vanuatu, John's 57th country. (The count

for Mary is trickier, because she has not been getting off the ship at recent stops in Indonesia and

the Solomon Islands.) Vanuatu has been an independent republic since 1980 and consists of ~ 83

volcanic islands.

We landed on the Ambrym Island, which is dominated by the active volcanoes Mt. Benbow (3806 feet

high above sea level) and Mt. Marum (4167 feet high above sea level). Wikipedia says that both

are almost continuously active, often (although not right now) with molten lava lakes in their caldera.

This is exceedingly interesting, but it played no part in our day. We were here only for cultural

reasons, to see the famous "Rom Dance" that is documented here.

As is almost universally the case, the people were very friendly. I spoke a little with a few

school children; they seemed comfortable with English. Here, as elsewhere, there is a widespread

tradition of elaborate woodcarving. It would have been a pleasure to partake ... but we already

have too much "stuff" and (on this trip) too much baggage. Still, it felt like a golden opportunity

missed.

A lot of cultural significance was hinted at but lost to us, as in this wood carving that is being

engulfed by a strangler fig tree.

The Rom Dance was performed in a field surrounded by most of the passengers of our ship. This

gave it rather too much the flavor of a performance rather than a mystical ritual. Still, it was

an impressive pageant. This is a panorama: scroll right to see it all. In the distance at right,

the dance is just getting started.

Short movie near the start of the Rom Dance

Paraphrasing Wikipedia: "The Rom dance is a sacred, traditional ritual performed by men on

Ambrym Island, Vanuatu. It is known for its complex masks, elaborate costumes made of dried

banana leaves, deep connection to spiritual beliefs, magic, and ancestor veneration. The ritual

includes hypnotic costumed dances, haunting bamboo flute music, and chants from associated

"nambas" (warriors) who provide protection. The costumes and masks are often destroyed after the

ceremony to prevent spirits from haunting the dancers." Explanations given on our ship emphasized

that a primary role of the dance is to enhance the social stature of the dancers. That is, it is

less about rites of passage, e. g. from boy to man, and more about the standing of the dancers in

the community. As is normally the case, much nuance is withheld from outsiders and, indeed, even

from non-participants such as women. The dance that was performed for us lasted about an hour.

The authentic ritual, properly performed, lasts much longer.

Dancer (detail)

Our expedition leader told us that this is a (or THE) chief of the tribe, now 82 years old and in

fine health. He looks essentially identical to a picture of him 10 years ago that we we were shown

in our end-of-day expedition briefing. Vanuatu is widely described as a happy place to live.

The curved tusks are from a pig. These are raised and allowed to grow the longest possible tusks

as part of the ritual of the Rom dance. The length of the tusks is a sign of the status of the

person who wears it. Used to be (but not today) that a pig was slaughtered and enjoyed in a feast

associated with the dance.

Judging from the impressive tusks and from his actions, this is another leader of the dance.

Here is a short movie near the end of the Rom Dance.

We docked at Lautoka on the north-western, dry side of Viti Levu, the main island of Fiji.

Fortunately, a last-minute change in the schedule of the ship had us staying overnight. I was

therefore able to arrange a full day of birding with an excellent local guide, Pastor Vilikesa

Masibalavu ( vmasibalavu@gmail.com ). He took me to the Nausari Highlands of Western Fiji, the

nearest area with pristine native mountain forest. Unfortunately, even here, development --

especially logging -- is rapidly encroaching, and the wondeful birds of Fiji that used to be easy

are getting harder. Today happened to be a particularly quiet day, and heavy rain started soon

after noon. Mr. Masibalavu worked hard to get me new birds, and in the end, I got 8 species.

His recommendation is that birding is much more productive on the south-east side of the island

via arrival at the capital city of Suva.

Fiji woodswallow (This Fiji endemic was my first life bird of the day, gotten easily while driving

still about half way up into the mountains.)

Vanikoro flycatcher (This female was my second life bird of the day, now in the pristine mountain forest.

I got a much better look and picture of another female and a male at Dravuni village tomorrow.)

Barking pigeon (This endemic life bird landed just for the moment that gave me this poor picture.

We heard it "bark" several times but never got another look.)

This female Sulphur-breasted myzomela is definitively my life bird, but I got a better look at a

better looking male tomorrow.

The Fiji endemic Chestnut-throated flycatcher was my prize life bird of the day -- simply gorgeous.

Slaty monarch -- not a good picture of this slate-gray bird with prominent white spectacles ...

but it is a Fiji endemic and it was the 6th and last life bird that I got before the skies opened

and rain inundated the mountains. We waited a little while, but this rain clearly was serious,

so we drove back to the vicinity of Lautoka. There, it was merely cloudy, and we were able to

get a few lowland species. One that we saw briefily but not well enough to take was the endemic

Fiji goshawk. Two of them swooped by the car after prey, but I did not get a good enough look.

Polynesiqan triller (Lalage maculosa pumila on Viti Levu) is my 7th life bird of the day.

We glimpsed it in many places, but this was taken in the outskirts of Lautoka, very near where

the Fiji parrotfinch was seen, below.

Fiji parrotfinch -- this beautiful male -- was my last life bird of the day. We had looked for

it and gotten glimpses briefly both in the mountains and near Lautoka. It kept eluding us. Also,

most birds that I glimpsed were all-green females. This male showed up and perched conveniently

on a wire just as we were about to give up for the day. It is a Fiji endemic.

I managed to arrange what I thought was a private bird guide at Kadavu Village, and a husband-and-wife

team were there on schedule at my zodiac landing. But they came over to Dravuni from the main island,

Kadavu, and they knew essentially nothing about birds. They were visibly pessimistic that I could see

the local endemic parrot, and indeed, there was no sign of any interesting birds in the surrounding

forest. The pair was helpful in making me feel safe to carry the expensive camera into the wild, and

they helped to carry my gear. But they were essentially unhelpful in finding birds. I managed to get

better views than on Viti Levu of the following two birds. But they were new already on Sept. 27, so

I got no new birds today.

Male sulphur-breasted myzomela in gardens in Dravuni village. This is a not-very-sharp picture that

has been rescued as much as possible from motion blur. The bird -- of course -- flitted constantly.

Vanikoro flycatcher (On September 27, I only saw a female and I did not see her well. This is a male.

You can also see why it used to be called Vanikoro broadbill.)

Vanikoro flycatcher (much better views of a female)

Approaching sunset on a nice day in Fiji. At least I got better views of two good birds.

And as always: We had a very comfortable day on Seabourn Pursuit, relaxing for both Mary and me.

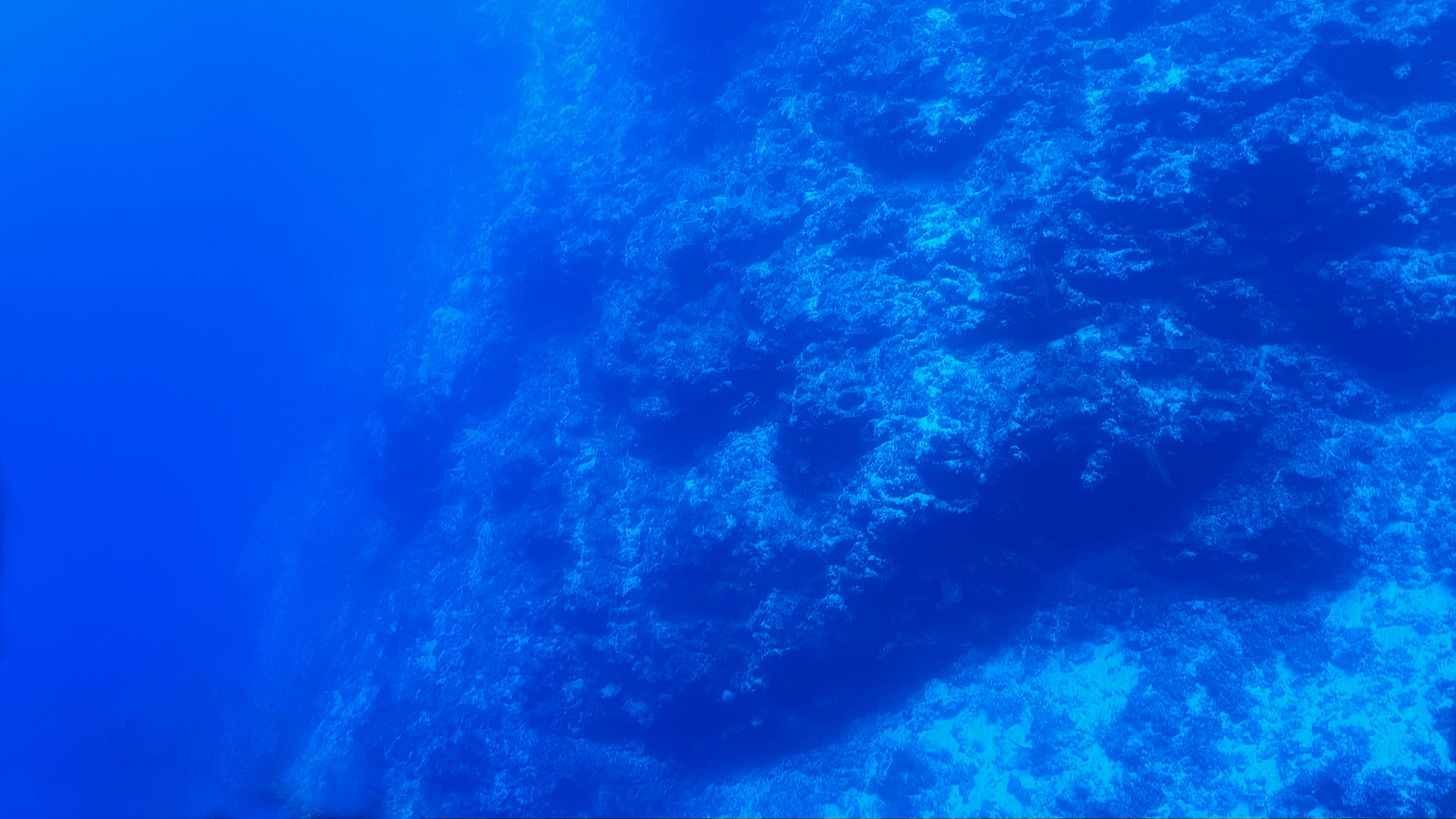

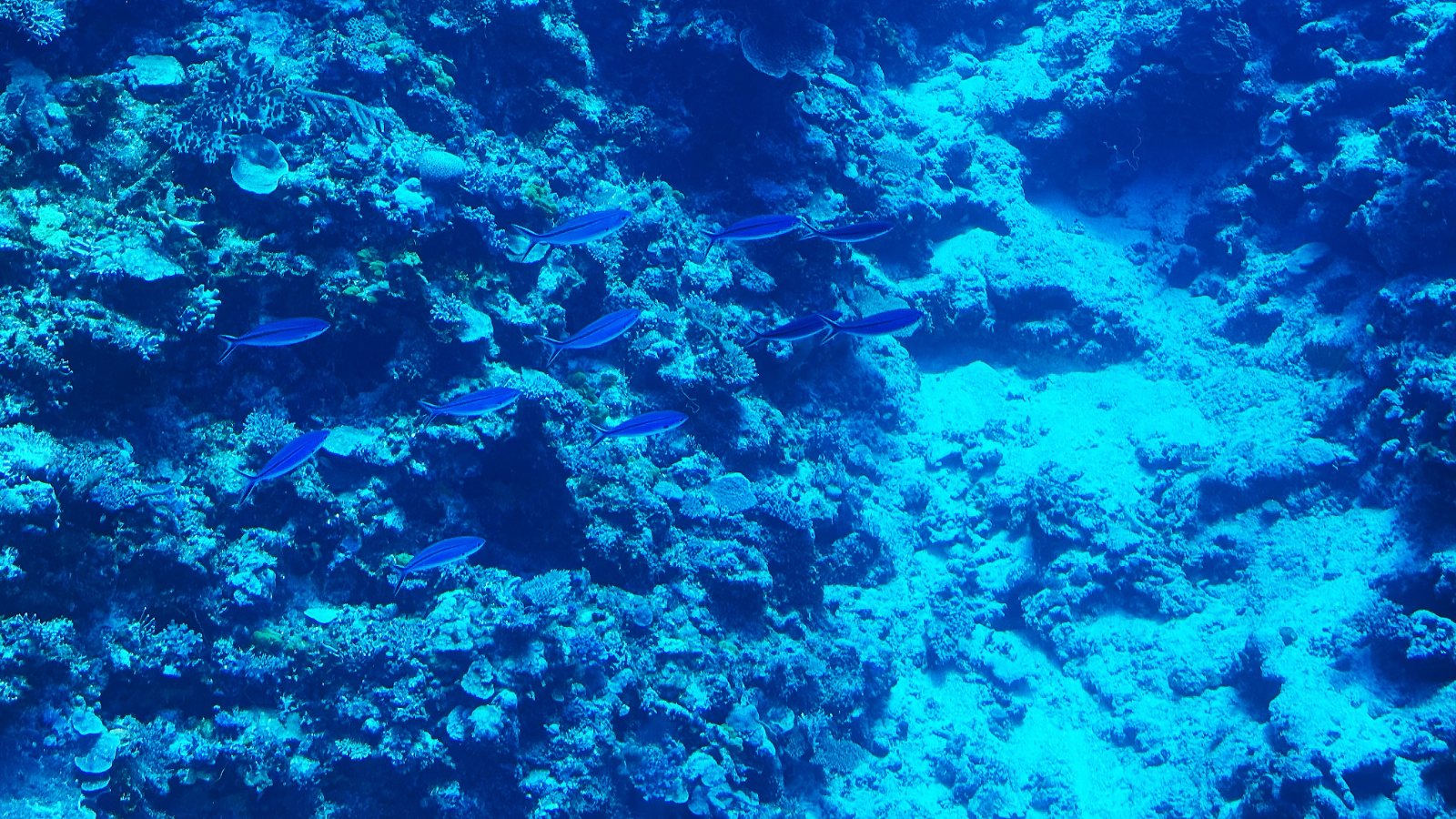

Today, we took our first submarine dive of the trip (a previous attempt was aborted because of

rough weather). We dove to about 40 m depth, limited by the depth to which rescue scuba divers could

easily go in the exceedingly unlikely event of trouble. The sub model has been in use by many ships

for many years and has a perfect safety record. But an electrical glitch on the second ship's sub kept

the crew conservative for dives during this cruise. It was not really a problem, because most of the

best scenery is within about 40 m of the surface, where at least some sunlight makes photosynthesis

possible. The water today was unusually clear, and the scenery was among the best that the experienced

sub drivers have seen. Mary was not feeling well before the dive and got sick in the sub while we

bobbed at the surface, but she kept this from being a problem for the rest of us, and she enjoyed the

dive immensely. We immediately signed up for one more dive during this part of the cruise, on Oct. 8.

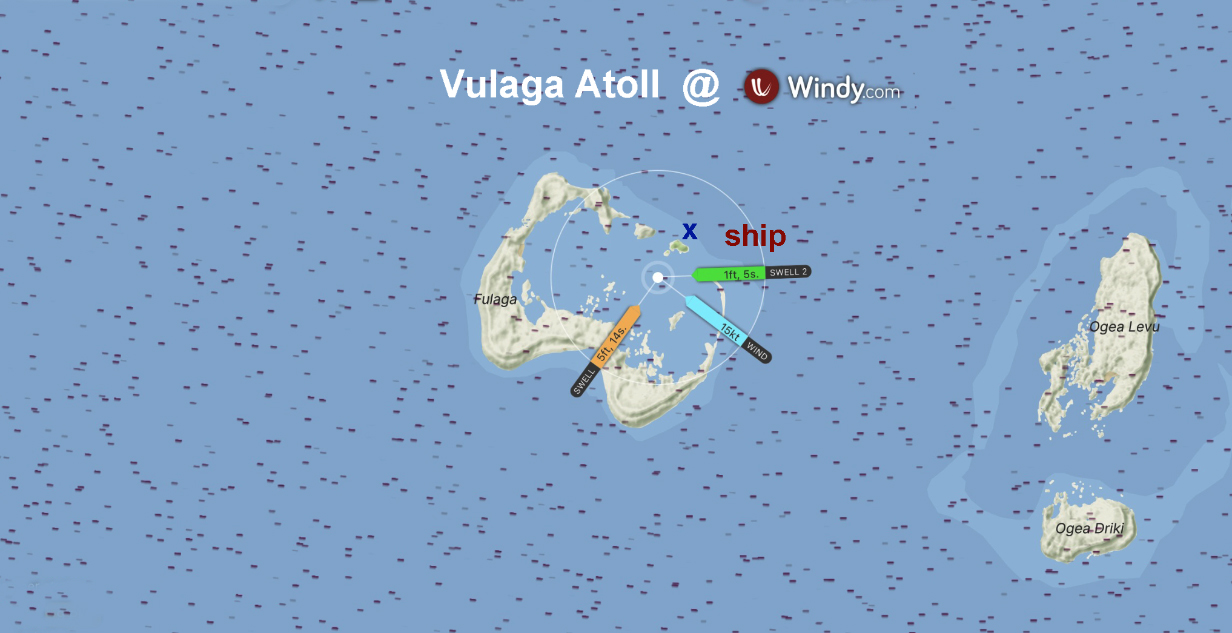

Windy.com map of Vulaga atoll, showing where our ship was positioned and where our dive took place

down the outer wall of the atoll. Seas were slightly rough: the zodiac that took as to and from the

sub bobbed up and down with respect to the sub by about +- 1 foot. Getting on and off the sub was

easy. Being inside while we bobbed was not fun. For "calibration", note that American astronauts

who waited after mission splashdown on the ocean to be picked up by rescue divers often said that

the hardest part of a space flight is the wait in the bobbing space capsule on the ocean. We empathize.

I was OK but worried about Mary. She felt bad but survived well enough to want to try it again.

The dive was spectacular. First, the setting:

This shows the atoll of Vulaga in the direction of the island (at right) in front of which we dove.

The zodiac that is going toward the right has the 6 passengers who took the dive before ours. The

zodiac that is heading mostly upward toward the deep channel into the lagoon is taking passengers to

a landing at a village on the far side of the lagoon.

This picture better sets the scene -- it shows the islands just left of the deep-water channel into

the lagoon in the previous picture.

Here the sub is loaded with the passengers for the dive before ours and is ready to submerge.

Conditions look rather calmer than they were for us.

Starting to dive: The zodiac that brought the passengers -- at left -- now has only its driver,

and the zodiac that oversees the dive operation is stationed at right. The sub is at all times in

contact with the surface and reports conditions (e. g., oxygen level 20.9 % and 1-atmosphere pressure)

to the surface periodically throughout the dive. At all times, all conditions felt safe and completely

under control. The only discomfort -- for us, though apparently not so much for people before us --

was bobbing on the surface at the beginning and end of our dive. This was in no sense dangerous; it

was just not fun. Notice that the current has been carrying the sub toward the right. I think that

they moved back toward the left for our dive.

This is a front view of the "Cruise Sub 7-300" model submarine that Seabourn uses. They are made

by U-Boat Worx. The the "300" means that the sub is rated to dive to 300 m ~ 1000 feet depth.

In operation, two sets of 3 seats each are rotated as shown above so that passengers look out

through a 20-cm-thick (7.8 inches thick) acrylic window that has the same index of refraction as

water. Under water, the window seems to disappear. During loading and unloading, the seat sections

are rotated to face the central column though which you enter and leave. This is also where the

sub pilot sits. The environment feels cramped during entry and exit but is entirely adequate.

Once you dive, there is no sense of claustrophobia.

This is Seabourn's video

on submarine operations. They are exactly right: The experience is magical. The acrylic window

vanishes completely, and one feels comfortably immersed in the expansive environment. Mary and I are