Several billion years after the Big Bang, the Universe went through a

``quasar era'' when high-energy active galactic nuclei (AGNs) were more than

10,000 times as numerous as they are now. Quasars must then have been standard

equipment in most large galaxies. Since that time, AGNs have been dying out.

Now quasars are exceedingly rare, and even medium-luminosity AGNs such as

Seyfert galaxies are uncommon. The only activity that still occurs in many

galaxies is weak. A paradigm for what powers this activity is well established

through the observations and theoretical arguments that are outlined in the

previous article. AGN engines are believed to be supermassive black holes

(BHs) that accrete gas and stars and so transform gravitational potential

energy into radiation. Expected BH masses are

![]()

![]() 106 -

109.5 M

106 -

109.5 M![]() .

A wide array of phenomena can be understood within this

picture. But the subject has had an outstanding problem: there was no dynamical

evidence that BHs exist. The search for BHs has therefore become one of the

hottest topics in extragalactic astronomy.

.

A wide array of phenomena can be understood within this

picture. But the subject has had an outstanding problem: there was no dynamical

evidence that BHs exist. The search for BHs has therefore become one of the

hottest topics in extragalactic astronomy.

Since most quasars have switched off, dim or dead engines - starving black holes - should be hiding in many nearby galaxies. This means that the BH search need not be confined to the active galaxies that motivated it. In fact, definitive conclusions are much more likely if we observe objects in which we do not, as Alan Dressler has said, ``have a searchlight in our eyes.'' Also, it was necessary to start with the nearest galaxies, because only then could we see close enough to the center so that the BH dominates the dynamics. Since AGNs are rare, nearby galaxies are not particularly active. For these reasons, it is no surprise that the search first succeeded in nearby, inactive galaxies.

This WWW review discusses stellar dynamical evidence for BHs in inactive and weakly active galaxies. Stellar motions are a particularly reliable way to measure masses, because stars cannot be pushed around by nongravitational forces. The price is extra complication in the analysis: the dynamics are collisionless, so random velocities can be different in different directions. This is impossible in a collisional gas. As we shall see, much effort has gone into making sure that unrecognized velocity anisotropy does not lead to systematic errors in mass measurements.

At the beginning of 2000, dynamical evidence for central dark objects had been published for 17 galaxies. With the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) pursuing the search, the number of detections is growing rapidly. Already we can ask demographic questions. Two main results have emerged. First, the numbers and masses of central dark objects are broadly consistent with predictions based on quasar energetics. Second, the central dark mass correlates with the mass of the elliptical-galaxy-like ``bulge'' component of galaxies. What is less secure is the conclusion that the central dark objects must be BHs and not (for example) dense clusters of brown dwarf stars or stellar remnants. Rigorous arguments against such alternatives are available for only two galaxies. Nevertheless, these two objects and the evidence for dark masses at the centers of almost all galaxies that have been observed are taken as strong evidence that the AGN paradigm is essentially correct.

The qualitative discussion of the previous section can be turned into a

quantitative estimate for

![]() as follows. The quasar population produces an

integrated comoving energy density of

as follows. The quasar population produces an

integrated comoving energy density of

In fact, the brightest quasars must have had much higher masses. A BH

cannot accrete arbitrarily large amounts of mass to produce arbitrarily high

luminosities. For a given ![]() ,

there is a maximum accretion rate above

which the radiation pressure from the resulting high luminosity blows away the

accreting matter. This ``Eddington limit'' is discussed in the preceeding

article. Eddington luminosities of

,

there is a maximum accretion rate above

which the radiation pressure from the resulting high luminosity blows away the

accreting matter. This ``Eddington limit'' is discussed in the preceeding

article. Eddington luminosities of

![]() erg s-1

erg s-1 ![]() 1014

1014 ![]() require BHs of mass

require BHs of mass

![]()

![]() 109 M

109 M![]() .

These

arguments define the parameter range of interest:

.

These

arguments define the parameter range of interest:

![]()

![]() 106 to

109.5 M

106 to

109.5 M![]() .

The highest-mass BHs are likely to be rare, but low-mass

objects should be ubiquitous. Are they?

.

The highest-mass BHs are likely to be rare, but low-mass

objects should be ubiquitous. Are they?

The answer appears to be ``yes''. The majority of detections on which this conclusion is based are stellar-dynamical. However, finding BHs is not equally easy in all galaxies. This results in important selection effects that need to be understood for demographic studies. Therefore we begin with a discussion of techniques. We then give three examples that highlight important aspects of the search. NGC 3115 is a particularly clean detection that illustrates the historical development of the search. M31 is one of the nearest galaxies and contains a new astrophysical phenomenon connected with BHs. Finally, the strongest case that the central mass is a BH and not a dark cluster of stars or stellar remnants is the one in our own Galaxy.

Dynamical mass measurement is conceptually simple. If random motions are

small, as they are in a gas, then the mass M(r) within radius r is

M(r) =

V2 r / G. Here V is the rotation velocity and G is the gravitational

constant. In stellar systems, some dynamical support comes from random

motions, so M(r) depends also on the velocity dispersion ![]() .

The

measurement technique is best described in the idealized case of spherical

symmetry and a velocity ellipsoid that points at the center. Then

the first velocity moment of the collisionless Boltzmann equation gives

.

The

measurement technique is best described in the idealized case of spherical

symmetry and a velocity ellipsoid that points at the center. Then

the first velocity moment of the collisionless Boltzmann equation gives

There is one tricky problem with this analysis, and it follows directly

from Equation 2. Rotation and random motions contribute similarly to M(r),

but the

![]() term is multiplied by a factor that depends on the

velocity anisotropy and that can be less than 1. Galaxy formation can easily

produce a radial velocity dispersion

term is multiplied by a factor that depends on the

velocity anisotropy and that can be less than 1. Galaxy formation can easily

produce a radial velocity dispersion ![]() that is larger than the

azimuthal components

that is larger than the

azimuthal components

![]() and

and

![]() .

Then the third and

fourth terms inside the brackets in Equation 2 are negative; they can be as

small as -1 each. In fact, they can largely cancel the first two terms,

because the second term cannot be larger than +1, and the first is

.

Then the third and

fourth terms inside the brackets in Equation 2 are negative; they can be as

small as -1 each. In fact, they can largely cancel the first two terms,

because the second term cannot be larger than +1, and the first is ![]() in many galaxies. This explains why ad hoc anisotropic models have

been so successful in explaining the kinematics of giant ellipticals without

BHs. But how anisotropic are the galaxies?

in many galaxies. This explains why ad hoc anisotropic models have

been so successful in explaining the kinematics of giant ellipticals without

BHs. But how anisotropic are the galaxies?

Much effort has gone into finding the answer. The most powerful technique is

to construct self-consistent dynamical models in which the density distribution

is the linear combination

![]() of the density

distributions

of the density

distributions ![]() of the individual orbits that are allowed by the

gravitational potential. First the potential is estimated from the light

distribution. Orbits of various energies and angular momenta are then calculated

to construct a library of time-averaged density distributions

of the individual orbits that are allowed by the

gravitational potential. First the potential is estimated from the light

distribution. Orbits of various energies and angular momenta are then calculated

to construct a library of time-averaged density distributions ![]() .

Finally, orbit occupation numbers Ni are derived so that the projected and

PSF-convolved model agrees with the observed kinematics. Some authors also

maximize

.

Finally, orbit occupation numbers Ni are derived so that the projected and

PSF-convolved model agrees with the observed kinematics. Some authors also

maximize

![]() ,

which is analogous to an entropy. These

procedures allow the stellar distribution function to be as anisotropic as it

likes in order (e.g.) to try to explain the observations without a BH. In

the end, such models show that real galaxies are not extremely anisotropic. That

is, they do not take advantage of all the degrees of freedom that the physics

would allow. However, this is not something that one could take for granted.

Because the degree of anisotropy depends on galaxy luminosity, almost all BH

detections in bulges and low-luminosity ellipticals (which are nearly isotropic)

are based on stellar dynamics, and almost all BH detections in giant ellipticals

(which are more anisotropic) are based on gas dynamics.

,

which is analogous to an entropy. These

procedures allow the stellar distribution function to be as anisotropic as it

likes in order (e.g.) to try to explain the observations without a BH. In

the end, such models show that real galaxies are not extremely anisotropic. That

is, they do not take advantage of all the degrees of freedom that the physics

would allow. However, this is not something that one could take for granted.

Because the degree of anisotropy depends on galaxy luminosity, almost all BH

detections in bulges and low-luminosity ellipticals (which are nearly isotropic)

are based on stellar dynamics, and almost all BH detections in giant ellipticals

(which are more anisotropic) are based on gas dynamics.

One of the best stellar-dynamical BH cases is the prototypical S0 galaxy NGC 3115. The left panel above is an HST WFPC2 color image of NGC 3115 showing the galaxy's central disk of stars and nuclear star cluster. The right panel shows a model of the nuclear disk. The center panel shows the difference. It emphasizes the nuclear star cluster - a tiny, dense cusp of stars like those expected around a BH. Brightness is proportional to the square root of intensity. All panels are 11.6 arcsec square. [This figure is taken from Kormendy et al. 1996, ApJ, 459, L57.]

NGC 3115 is especially suitable for the BH search because it is very symmetrical and almost exactly edge-on. It provides a good illustration of how the BH search makes progress. Unlike some discoveries, finding a supermassive BH is rarely a unique event. Rather, an initial dynamical case for a central dark object gets stronger as observations improve. Eventually, the case becomes definitive. This has happened in NGC 3115 through the study of the central star cluster. Later, still better observations may accomplish the next step, which is to strengthen astrophysical constraints enough so that all plausible BH alternatives (clusters of dark stars) are eliminated. This has happened for our Galaxy (§3.4) but not yet for NGC 3115.

The kinematics of NGC 3115 show the signature of a central dark object.

The above plots show rotation velocities (lower panel) and velocity dispersions

(upper panel) along the major axis of NGC 3115 as observed at three different

spatial resolutions. Resolution  is the Gaussian dispersion radius of the PSF; in the case of the HST

observations, this is negligible compared to the aperture size of 0.21 arcsec

[From Kormendy et al. 1996,

Astrophys. J. Lett., 459, L57.]

is the Gaussian dispersion radius of the PSF; in the case of the HST

observations, this is negligible compared to the aperture size of 0.21 arcsec

[From Kormendy et al. 1996,

Astrophys. J. Lett., 459, L57.]

The original BH detection was based on the blue crosses. Already at resolution

0.44 arcsec, the central kinematic gradients are steep. The apparent central

dispersion,

![]() = 300

km s-1, is much higher than normal for a galaxy of absolute magnitude

MB = -20.0.

Therefore, isotropic dynamical models imply that NGC 3115 contains a dark mass

= 300

km s-1, is much higher than normal for a galaxy of absolute magnitude

MB = -20.0.

Therefore, isotropic dynamical models imply that NGC 3115 contains a dark mass

M

M![]() .

Maximally anisotropic models allow

smaller masses,

.

Maximally anisotropic models allow

smaller masses,

![]()

![]() 108 M

108 M![]() ,

but isotropy is more likely given

the rapid rotation.

,

but isotropy is more likely given

the rapid rotation.

Since that time, two generations of improved observations have become

available. The green points were obtained with the Subarcsecond

Imaging Spectrograph (SIS) and the Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope (CFHT). This

incorporates tip-tilt optics to improve the atmospheric PSF. The observations

with the HST Faint Object Spectrograph (FOS) have still higher

resolution. If the BH detection is correct, then the apparent rotation and

dispersion profiles should look steeper when they are observed at higher

resolution. This is exactly what is observed. If the original dynamical models are ``reobserved'' at the improved resolution, the

ones that agree with the new data have

![]() = (1 to 2)

= (1 to 2)  109

M

109

M![]() .

.

Finally, a definitive detection is provided by the HST observations

of the nuclear star cluster. Its true velocity dispersion is underestimated

in the figure above, because the projected value includes bulge light from in

front of and behind the center. When this light is subtracted, the velocity

dispersion of the nuclear cluster proves to be 600 +- 40 km s-1.

This is the highest dispersion measured in any galactic center. The velocity

of escape from the nucleus would be much smaller,

![]() km s-1, if it

consisted only of stars. Without extra mass to bind it, the cluster would fling

itself apart in about 109 yr. Independent of any velocity anisotropy,

the nucleus must contain an unseen object of mass

109

M

km s-1, if it

consisted only of stars. Without extra mass to bind it, the cluster would fling

itself apart in about 109 yr. Independent of any velocity anisotropy,

the nucleus must contain an unseen object of mass

109

M![]() .

This is consistent with the modeling results. The dark object is more than 25

times as massive as the visible star cluster. We know of no way to make a star

cluster that is so nearly dark, especially without overenriching the visible

stars with heavy elements. The most plausible explanation is a BH. This would

easily have been massive enough to power a quasar.

.

This is consistent with the modeling results. The dark object is more than 25

times as massive as the visible star cluster. We know of no way to make a star

cluster that is so nearly dark, especially without overenriching the visible

stars with heavy elements. The most plausible explanation is a BH. This would

easily have been massive enough to power a quasar.

M31 is the highest-luminosity galaxy in the Local Group. At a distance of 0.77 Mpc, it is the nearest giant galaxy outside our own. It can therefore be studied in unusual detail.

M31 contains the nearest example of a nuclear star cluster embedded in a normal bulge. The above figure shows an HST, WFPC2 color image of M31 constructed from I-, V- and 3000 Å-band, PSF-deconvolved images obtained by Lauer et al. (1998, Astron. J., 116, 2263). The scale is 0.0228 arcsec pixel-1. The nucleus appears double. This is very surprising. At a separation of 2r = 1.7 pc, a relative velocity of 200 km s-1 implies a circular orbit period of 50,000 yr. If the nucleus consisted of two star clusters in orbit around each other, as the above image might suggest, then dynamical friction would make them merge within a few orbital times. Therefore it is unlikely that the simplest possible explanation is correct: we are not observing the last stages of the digestion of an accreted companion galaxy.

Rotation curve (bottom) and velocity dispersion profile (top) of the nucleus with foreground bulge light subtracted. The sharp dispersion peak is centered on the blue star cluster embedded in the left brightness peak. This sugggests that the BH is in the blue cluster. [This figure is adapted from Kormendy & Bender 1999, Astrophys. J., 522, 772.]

The nucleus rotates rapidly and has a steep velocity dispersion gradient.

Dynamical analysis shows that M31 contains a central dark mass

![]() =

=

![]() M

M![]() .

The possible effects of velocity anisotropy have been checked and provide no

escape. Furthermore, the asymmetry provides an almost independent check of

the BH mass, as follows.

.

The possible effects of velocity anisotropy have been checked and provide no

escape. Furthermore, the asymmetry provides an almost independent check of

the BH mass, as follows.

The observed sharp peak in the velocity dispersion profile is approximately

centered on the fainter nucleus shown in the WFPC2 image. In fact, it is

centered almost exactly on the cluster of blue stars that is embedded in this

nucleus. This suggests that the BH is in the blue cluster. This hypothesis

can be tested by finding the center of mass of the asymmetric distribution of

starlight plus a dark object in the blue cluster. The mass-to-light ratio of

the stars is provided by dynamical models of the bulge at larger radii. If the

galaxy is in equilibrium, then the center of mass should coincide with the

center of the bulge. It does, provided that

![]() =

=

![]() M

M![]() .

Remarkably, the same BH mass explains both the kinematics and the asymmetry of

the nucleus.

.

Remarkably, the same BH mass explains both the kinematics and the asymmetry of

the nucleus.

An explanation of the mysterious double nucleus has been proposed by

Scott Tremaine. He suggests that both nuclei are part of a single eccentric

disk of stars. The brighter nucleus is farther from the barycenter; it results

from the lingering of stars near the apocenters of very elongated orbits. The

fainter nucleus is produced by an increase in disk density toward the center.

The model depends on the presence of a BH to make the potential almost

Keplerian; then the alignment of orbits in the eccentric disk may be maintained

by the disk's self-gravity. Tremaine's model was developed to explain the

photometric and kinematic asymmetries as seen at resolution  = 0.44 arcsec. It is also consistent with the new data

above that has

= 0.44 arcsec. It is also consistent with the new data

above that has  = 0.27 arcsec. The high

velocity dispersion near the BH, the low dispersion in the offcenter nucleus,

and especially the asymmetric rotation curve are signatures of the eccentric,

aligned orbits.

= 0.27 arcsec. The high

velocity dispersion near the BH, the low dispersion in the offcenter nucleus,

and especially the asymmetric rotation curve are signatures of the eccentric,

aligned orbits.

Most recently, spectroscopy of M31 has been obtained with the HST Faint Object Camera. This improves the spatial resolution by an additional factor of about 5. At this resolution, there is a 0.25 arcsec wide region centered on the faint nucleus in which the velocity dispersion is 440 +- 70 km s-1. This is further confirmation of the existence and location of the BH.

We do not know whether the double nucleus is the cause or an effect of the offcenter BH. However, offcenter BHs are an inevitable consequence of hierarchical structure formation and galaxy mergers. If most large galaxies contain BHs, then mergers produce binary BHs and, in three-body encounters, BH ejections with recoil. How much offset we see, and indeed whether we see two BHs or one or none at all, depend on the relative rates of mergers, dynamical friction, and binary orbit decay. Offcenter BHs may have much to tell us about these and other processes. Already there is evidence in NGC 4486B for a second double nucleus containing a BH.

M

M

Our Galaxy has long been known to contain the exceedingly compact radio

source Sgr A*. Interferometry gives its diameter as 63rs by less

than 17rs, where

rs = 0.06 AU =

![]() cm is the

Schwarzschild radius of a

cm is the

Schwarzschild radius of a

M

M![]() BH. It is easy to be

impressed by the small size. But as an AGN, Sgr A* is feeble: its radio

luminosity is only 1034 erg s-1

BH. It is easy to be

impressed by the small size. But as an AGN, Sgr A* is feeble: its radio

luminosity is only 1034 erg s-1

.

The infrared and high-energy luminosities are higher, but there is no

compelling need for a BH on energetic grounds. To find out whether the Galaxy

contains a BH, we need dynamical evidence.

.

The infrared and high-energy luminosities are higher, but there is no

compelling need for a BH on energetic grounds. To find out whether the Galaxy

contains a BH, we need dynamical evidence.

Getting it has not been easy. Our Galactic disk, which we see in the sky

as the Milky Way, contains enough dust to block all but ![]() 10-14 of

the optical light from the Galactic center. Measurements of the region around

Sgr A* had to await the development of infrared detectors. Much of the infrared

radiation is in turn absorbed by the Earth's atmosphere, but there is a useful

transmission window at 2.2

10-14 of

the optical light from the Galactic center. Measurements of the region around

Sgr A* had to await the development of infrared detectors. Much of the infrared

radiation is in turn absorbed by the Earth's atmosphere, but there is a useful

transmission window at 2.2  m wavelength. Here the extinction toward the

Galactic center is a factor of

m wavelength. Here the extinction toward the

Galactic center is a factor of ![]() 20. This is large but manageable.

Early infrared measurements showed a rotation velocity of

20. This is large but manageable.

Early infrared measurements showed a rotation velocity of

100 km

s-1 and a small rise in velocity dispersion to

100 km

s-1 and a small rise in velocity dispersion to

120 km s-1 at

the center. These were best fit with a BH of mass

120 km s-1 at

the center. These were best fit with a BH of mass

![]()

![]() 106 M

106 M![]() ,

but the evidence was not very strong. Since then, a series of spectacular

technical advances have made it possible to probe closer and closer to the

center. As a result, the strongest case for a BH in any galaxy is now our own.

,

but the evidence was not very strong. Since then, a series of spectacular

technical advances have made it possible to probe closer and closer to the

center. As a result, the strongest case for a BH in any galaxy is now our own.

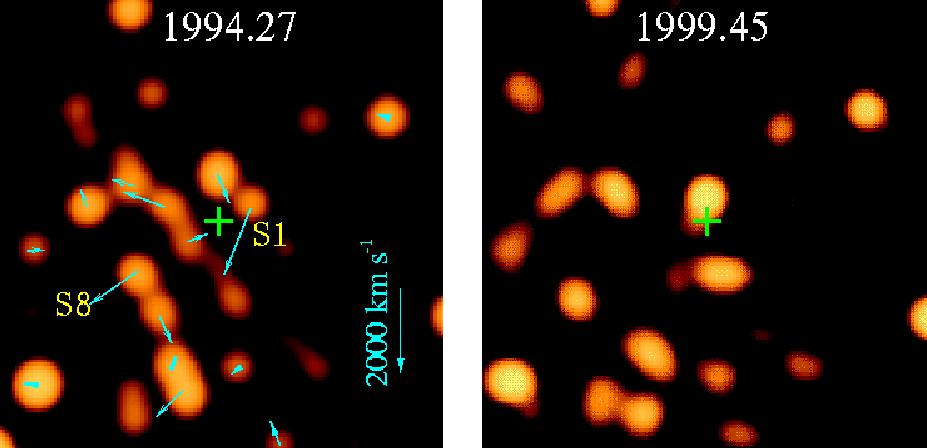

Most remarkably, two independent groups led by Reinhard Genzel and Andrea

Ghez have used speckle imaging to measure proper motions - the velocity

components perpendicular to the line of sight - in a cluster of stars at radii

r = 0.02 pc from Sgr A* (below). When combined

with complementary measurements at larger radii, the result is that the

one-dimensional velocity dispersion increases smoothly to 420 +- 60

km s-1 at

pc. Stars at this radius revolve around the Galactic

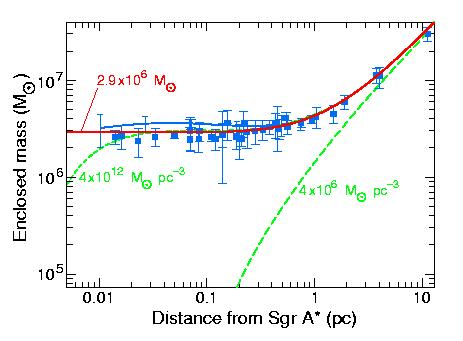

center in a human lifetime! The mass M(r) inside radius r

is also shown below. Outside a few pc, the mass distribution is dominated by

stars, but as

pc. Stars at this radius revolve around the Galactic

center in a human lifetime! The mass M(r) inside radius r

is also shown below. Outside a few pc, the mass distribution is dominated by

stars, but as

![]() ,

M(r) flattens to a constant,

,

M(r) flattens to a constant,

![]() =

=

M

M![]() .

Velocity anisotropy is not an uncertainty; it

is measured directly and found to be small. The largest dark cluster that is

consistent with these data would have a central density of about

.

Velocity anisotropy is not an uncertainty; it

is measured directly and found to be small. The largest dark cluster that is

consistent with these data would have a central density of about

M

M![]() pc-3. This is inconsistent with astrophysical constraints (§5).

Therefore, if the dark object is not a BH, the alternative would have to be

comparably exotic. It is prudent to note that rigorous proof of a BH requires

that we spatially resolve relativistic velocities near the Schwarzschild radius.

This is not yet feasible. But the case for a BH in our own Galaxy is now very

compelling.

pc-3. This is inconsistent with astrophysical constraints (§5).

Therefore, if the dark object is not a BH, the alternative would have to be

comparably exotic. It is prudent to note that rigorous proof of a BH requires

that we spatially resolve relativistic velocities near the Schwarzschild radius.

This is not yet feasible. But the case for a BH in our own Galaxy is now very

compelling.

Images of the star cluster surrounding Sgr A* (green cross) at the epochs indicated. The arrows in the left frame show approximately where the stars have moved in the right frame. Star S1 has a total proper motion of about 1600 km s-1. [This figure is updated from Eckart & Genzel 1997, M. N. R. A. S., 284, 576 and was kindly provided by A. Eckart.]

Mass distribution implied by proper motion and radial velocity

measurements (blue points and curve). Long dashes (green) show the mass

distribution of stars if the infrared mass-to-light ratio is 2. The red

curve represents the stars plus a point mass

![]() =

=

M

M![]() .

Short green dashes provide an estimate of how non-pointlike the

dark mass could be: its

value is 1

.

Short green dashes provide an estimate of how non-pointlike the

dark mass could be: its

value is 1![]() worse than the solid

curve. This dark cluster has a core radius of 0.0042 pc and a central density

of

worse than the solid

curve. This dark cluster has a core radius of 0.0042 pc and a central density

of

M

M![]() pc-3. [This figure is updapted from Genzel

et al. 1997, M. N. R. A. S., 291, 219 and was kindly provided by

R. Genzel.]

pc-3. [This figure is updapted from Genzel

et al. 1997, M. N. R. A. S., 291, 219 and was kindly provided by

R. Genzel.]

The census of BH candidates as of January 2000 is given in Table 1. The table is divided into three groups - detections based on stellar dynamics, on ionized gas dynamics, and on maser disk dynamics (top to bottom). The rate of discovery is accelerating as HST pursues the search. However, we already have candidates that span the range of predicted masses and that occur in essentially every type of galaxy that is expected to contain a BH. Host galaxies include giant AGN ellipticals (the middle group), Seyfert galaxies (NGC 1068), normal spirals with moderately active nuclei (e.g., NGC 4594 and NGC 4258), galaxies with exceedingly weak nuclear activity (our Galaxy and M31), and completely inactive galaxies (M32 and NGC 3115).

However, no complete sample has been studied at high resolution. The detections in Table 1, together with low-resolution studies of larger samples of galaxies, support the hypothesis that BHs live in virtually every galaxy with a substantial bulge component. The total mass in detected remnants is consistent with predictions based on AGN energetics, within the rather large estimated errors in both quantities. (Updated black hole census as of March 2001 in postscript or PDF)

The main new demographic result is an apparent correlation between BH mass and the luminosity of the bulge part of the galaxy. More luminous bulges contain more massive black holes. Since M/L varies little from bulge to bulge, this implies that more massive bulges contain more massive black holes. Blue filled circles indicate BH masses based on stellar dynamics, green diamonds are based on ionized gas dynamics, and red squares are based on maser disk dynamics. It is reassuring that all three techniques are consistent with the same correlation. Note that the correlation is not with the total luminosity: if the disk is included, the correlation is considerably worse. Whether the correlation is real or not was still being tested at the beginning of 2000. The concern was selection effects. High-mass BHs in small galaxies are easy to see, so their scarcity is real. But low-mass BHs can hide in giant galaxies, so the correlation could have been only the upper envelope of a distribution that extends to smaller BH masses. By 2000 June, it was clear that the correlation is real. It implies that BH formation or feeding is connected with the mass of the high-density, elliptical-galaxy-like part of the galaxy. With the possible exception of NGC 4945 (a late-type galaxy for which the existence and luminosity of a bulge are uncertain), BHs have been found only in the presence of a bulge. However, the limits on BH masses in bulgeless galaxies like M33 were, in 2000.0, still consistent with the correlation. Current searches concentrate on the question of whether small BHs - ones that are significantly below the apparent correlation - can be found or excluded.

BH mass fractions are listed in Table 1 for cases in which the mass-to-light ratio of the stars has been measured. The median BH mass fraction is 0.29%. The quartiles are 0.07% and 0.9%.

The discovery of dark objects with masses

![]() =

106 to

109.5 M

=

106 to

109.5 M![]() in galactic nuclei is secure. But are they BHs? Proof requires measurement of relativistic velocities near the Schwarzschild radius,

rs = 2

in galactic nuclei is secure. But are they BHs? Proof requires measurement of relativistic velocities near the Schwarzschild radius,

rs = 2  / 108 M

/ 108 M AU. Even for M31,

this is only 8 x 10-7 arcsec.

HST spectroscopic resolution is only 0.1 arcsec.

The conclusion that we are finding BHs is based on physical arguments that BH

alternatives fail to explain the masses and high densities of galactic nuclei.

AU. Even for M31,

this is only 8 x 10-7 arcsec.

HST spectroscopic resolution is only 0.1 arcsec.

The conclusion that we are finding BHs is based on physical arguments that BH

alternatives fail to explain the masses and high densities of galactic nuclei.

The most plausible BH alternatives are clusters of dark objects produced

by ordinary stellar evolution. These come in two varieties, failed stars and

dead stars. Failed stars have masses m*

0.08 M

0.08 M![]() .

They never

get hot enough for the fusion reactions that power stars, i.e., the

conversion of hydrogen to helium. They have a brief phase of modest brightness

while they live off of gravitational potential energy, but after this, they

could be used to make dark clusters. They are called brown dwarf stars, and

they include planetary mass objects. Alternatively, a dark cluster could be

made of stellar remnants - white dwarfs, which have typical masses of 0.6

M

.

They never

get hot enough for the fusion reactions that power stars, i.e., the

conversion of hydrogen to helium. They have a brief phase of modest brightness

while they live off of gravitational potential energy, but after this, they

could be used to make dark clusters. They are called brown dwarf stars, and

they include planetary mass objects. Alternatively, a dark cluster could be

made of stellar remnants - white dwarfs, which have typical masses of 0.6

M![]() ;

neutron stars, which typically have masses of

;

neutron stars, which typically have masses of ![]() 1.4 M

1.4 M![]() ,

and

black holes with masses of several M

,

and

black holes with masses of several M![]() .

Galactic bulges are believed to form

in violent starbursts, so massive stars that turn quickly into dark remnants

would be no surprise. It is not clear how one could make dark clusters with the

required masses and sizes, especially not without polluting the remaining stars

with more metals than we see. But in the absence of direct proof that the dark

objects in galactic nuclei are BHs, it is important to examine alternatives.

.

Galactic bulges are believed to form

in violent starbursts, so massive stars that turn quickly into dark remnants

would be no surprise. It is not clear how one could make dark clusters with the

required masses and sizes, especially not without polluting the remaining stars

with more metals than we see. But in the absence of direct proof that the dark

objects in galactic nuclei are BHs, it is important to examine alternatives.

However, dynamical measurements tell us more than the mass of a potential BH. They also constrain the maximum radius inside which the dark stuff must live. Its minimum density must therefore be high, and this rules out the above BH alternatives in our Galaxy and in NGC 4258. High-mass remnants such as white dwarfs, neutron stars, and stellar BHs would be relatively few in number. The dynamical evolution of star clusters is relatively well understood; in the above galaxies, a sparse cluster of stellar remnants would evaporate completely in about 108 yr. Low-mass objects such as brown dwarfs would be so numerous that collision times would be short. Stars generally merge when they collide. A dark cluster of low-mass objects would become luminous because brown dwarfs would turn into stars.

More exotic BH alternatives are not ruled out by such arguments. For example, the dark matter that makes up galactic halos and that accounts for most of the mass of the Universe may in part be elementary particles that are cold enough to cluster easily. It is not out of the question that a cluster of these could explain the dark objects in galaxy centers without getting into trouble with any astrophysical constraints. So the BH case is not rigorously proved. What makes it compelling is the combination of dynamical evidence and the evidence from AGN observations. This is discussed in the previous article.

For many years, AGN observations were decoupled from the dynamical evidence for BHs. This is no longer the case. Dynamical BH detections are routine. The search itself is no longer the main preoccupation; we can concentrate on physical questions. New technical developments such as better x-ray satellites ensure that progress on BH astrophysics will continue to accelerate.

The search for BHs is reviewed in the following papers:

Kormendy, J., & Richstone, D. Ann. Rev. Astr. Astrophys. 33, 581 (1995)

Richstone, D., et al. Nature 395, A14 (1998)

In the following papers, quasar energetics are used to predict the masses of dead AGN engines:

Sotan, A. M.N.R.A.S. 200, 115 (1982)

Chokshi, A., & Turner, E. L. M.N.R.A.S. 259, 421 (1992)

Dynamical models of galaxies as linear combinations of individual orbits are discussed in

Schwarzschild, M. Astrophys. J. 232, 236 (1979)

Richstone, D. O., & Tremaine, S. Astrophys. J. 327, 82 (1988)

van der Marel, R. P., Cretton, N., de Zeeuw, P. T., & Rix, H.-W. Astrophys. J. 493, 613 (1998)

Gebhardt, K., et al. Astron. J. 119, 1157 (2000)

The BH detection in NGC 3115 is discussed in

Kormendy, J., & Richstone, D. Astrophys. J. 393, 559 (1992)

Kormendy, J., et al. Astrophys. J. Lett. 459, L57 (1996)

The BH detection in M31 is discussed in

Dressler, A., & Richstone, D. O. Astrophys. J. 324, 701 (1988)

Kormendy, J. Astrophys. J. 325, 128 (1988)

Tremaine's model for the double nucleus of M31 and new evidence for that model are in

Tremaine, S. Astron. J. 110, 628 (1995)

Kormendy, J., & Bender, R. Astrophys. J. 522, 772 (1999)

HST spectroscopy of the double nucleus of M31 is presented in

Statler, T. S., King, I. R., Crane, P., & Jedrzejewski, R. I. Astron. J. 117, 894 (1999)

The following are thorough reviews of the Galactic center:

Genzel, R., Hollenbach, D., & Townes, C. H. Rep. Prog. Phys. 57, 417 (1994)

Morris, M., & Serabyn, E. Ann. Rev. Astr. Astrophys. 34, 645 (1996)

The latest measurement of the size of the Galactic center radio source is by

Lo, K. Y., Shen, Z.-Q., Zhao, J.-H., & Ho, P. T. P. Astrophys. J. Lett. 508, L61 (1998)

The remarkable proper motion measurements of stars near Sgr A* and resulting conclusions about the Galactic center BH are presented in

Genzel, R., Eckart, A., Ott, T., & Eisenhauer, F. M.N.R.A.S. 291, 219 (1997)

Ghez, A. M., Klein, B. L., Morris, M., & Becklin, E. E. Astrophys. J. 509, 678 (1998)

Arguments against compact dark star clusters in NGC 4258 and the Galaxy are presented in

Maoz, E. Astrophys. J. Lett. 494, L181 (1998)

University of Texas Astronomy Home Page

John Kormendy (kormendy@astro.as.utexas.edu)